Recycle law thriving at 30

Wisconsin's recycling landscape adapts over the decades

Amy Dubruiel

IN THIS ISSUE: RECYCLING/E-CYCLING

- Recycle law thriving at 30

- E-cycle law turns 10

- Recycling Q&A

- E-cycling Q&A

- Recycle/e-cycle tips

©MARISSA MICHALKIEWICZ A front loader pushes materials toward the sorting lines at the Tri-County Materials Recovery Facility in Appleton.

©MARISSA MICHALKIEWICZ A front loader pushes materials toward the sorting lines at the Tri-County Materials Recovery Facility in Appleton. Can you remember back when you first learned about recycling?

Maybe it was a lesson in school or something you picked up at home. For many of us, recycling has been part of our lives for as long as we can recall.

This year marks the 30-year anniversary of Wisconsin’s recycling law, which established how we recycle, provided partial funding for local recycling programs and banned certain items from landfill or incinerator disposal. The recycling law and subsequent disposal bans apply everywhere in the state, including homes, businesses, schools, institutions and at special events.

Wisconsin’s recycling system recovers valuable materials, saves landfill space, reduces greenhouse gas emissions and keeps toxic materials out of the environment. It also is a major driver of the economy, supporting hundreds of community-based jobs and manufacturing in the state.

In 2018, local government recycling programs in Wisconsin, called responsible units, reported recycling over 420,000 total tons of landfill-banned paper plus metal, glass and plastic containers from households — an amount that has been consistent over the last 10 years.

Wisconsin has a strong history of recycling, but it is not without its challenges. Recycling programs have adapted to meet the needs of their customers while still implementing the law.

SWITCH TO SINGLE STREAM

The Tri-County Materials Recovery Facility, which opened in 2009 in Appleton, is a good example of a place that has adapted to changes in the recycling landscape. The MRF operates through a unique partnership formed in 2003 between Brown, Outagamie and Winnebago counties. It serves over 65 communities and recycles more than 100,000 tons of materials from households, schools and businesses annually.

Before becoming the DNR’s waste reduction and diversion coordinator in 2016, Jennifer Semrau worked for Winnebago County’s recycling program for 17 years, giving her a firsthand look at the Tri-County partnership.

One big change comes to mind when she thinks of her experience, Semrau said: “The shift from dual stream, where residents sorted their curbside recyclables by type, to single stream recycling, where residents commingle recyclables in a cart.”

The Tri-County MRF started laying the groundwork for the change in 2007 and two years later became the first publicly owned Wisconsin MRF to switch to single stream.

The benefits were multifold. Communities recycled more and collection became more efficient and safer for workers.

But with single stream recycling, contamination became a bigger issue. Long-held practices, such as encouraging residents to bundle newspapers together with twine or placing recyclables in plastic bags, became hinderances to recycling.

“Now, outreach is focused on keeping materials that get tangled in recycling equipment, like plastic bags or twine, out of the recycling stream,” Semrau noted. “When the Tri-County MRF was built, Winnebago County still utilized a line of workers dedicated to debagging recyclables.”

MARKETS DICTATE CHANGES

Some shifts in recycling have been due to broader changes in recycling markets and consumer behavior. Online shopping raised the demand for recycled fiber for manufacturing cardboard, and markets for some plastics fluctuated.

“Markets for #3-7 plastics used to be relatively nonexistent but had expanded around the time the Tri-County MRF was built. Since 2017, this market has diminished again,” Semrau said. “Whereas, the markets for #1 and 2 plastics have remained steady.”

The code on plastics indicates the type of resin used to manufacture the plastic. Some, like PVC, are not recyclable, while the recyclability of others depends on what is banned from landfill or incinerator disposal and their use in manufacturing new products.

As for other industry changes, some have been more subtle — not only did paper copies of newspapers decrease, but newspapers became smaller. Today’s plastic bottles and aluminum cans are thinner than their predecessors.

“Recycling programs often need to adapt and look for efficiencies,” Semrau said. “The Tri-County partnership is a great example of how three recycling programs pooled their resources to the benefit of the communities they serve.”

Before the partnership agreement, all three counties operated an MRF and a landfill, essentially competing for business. Today, Outagamie County runs the MRF, and facilities in Brown and Winnebago counties are transfer stations.

©DNR FILESBales of processed recyclables await shipment.

©DNR FILESBales of processed recyclables await shipment.CHALLENGES TO MEET

Perhaps the biggest industry change in recent years came in 2017, when a seismic shift occurred in recycling markets. That happened when China announced its “National Sword” policy, largely banning imports of certain recyclables, including many paper and plastics.

MRFs were forced to meet new contamination standards, which increased their costs, and adjust to new pricing for recyclables. To meet the challenges, many MRFs evaluated their operations and focused their outreach on controlling costs by reducing problematic materials that slowed operations or rendered materials unrecyclable.

In 2019, the DNR conducted a survey of MRFs to discover which contaminants were the most detrimental to operations.

“We wanted to learn which contaminants were causing the biggest issues so the DNR can provide accurate information to the public,” Semrau said.

Of the 41 MRFs that operate in the state, 30 responded to the survey. Plastic bags and film were noted as a top contaminant. These items get wrapped around machinery, causing problems with sorting lines.

“Workers need to manually cut out the bags when they are wrapped around equipment, which can take several hours a day,” Semrau said.

“Tanglers” such as rope or baling twine are another top contaminant for the same reason. Food contamination also ranked high among MRFs.

“Emptying and rinsing containers is an easy step that can have a lot of positive impact on the value of sorted recyclables,” Semrau said.

NO SHARPS, NO FILMS

Some materials are considered contaminants because there are not yet adequate recycling markets for them. Foam polystyrene packaging such as used for food and beverages must be taken off the line and landfilled. Bulky plastics like lawn chairs or toys must be sorted out as well.

Beyond slowing down operations, some contaminants pose a significant safety risk to workers. Sharps such as needles, syringes or lancets can enter facilities in unmarked plastic containers that are easily broken.

“Even in highly mechanized facilities, some hand sorting is required and in other facilities, a lot of sorting is done by hand,” Semrau explained. “If a worker gets stuck by a needle, they typically undergo months of testing for infectious diseases.”

If not the recycling bin, where do these items go? Many types of plastic film — including shopping bags, newspaper bags, dry cleaning bags and plastic wrap around toilet paper — can be recycled by placing them in collection bins at many grocery stores (if clean, dry and not mixed with other material).

Food waste can often be composted, and scrap metal can be taken to a municipal metal collection site or a private metal scrapper. For most of the other top contaminants, such as diapers or food waste that cannot be composted, the best disposal option is the garbage. However, there are several resources to help divert materials from landfills.

Find more information at dnr.wi.gov, search “What to recycle.”

LOOKING TO THE FUTURE

The next five years will continue to bring change to curbside recycling programs and MRFs. Starting next year, for example, plastics will be subject to export restrictions due to the Basel Convention.

While this international treaty was designed to address the movement of hazardous waste between nations, the issue of plastic waste in the marine environment has resulted in the new restrictions.

“The DNR will continue to evaluate and work with recycling programs to meet recycling challenges,” Semrau said. And that’s no different than it’s been for the past 30 years.

“While markets will always change and evolve, Wisconsin’s longstanding recycling program has provided valuable, consistent feedstock to recycling industries,” she said. “We celebrate the 30-year anniversary of the recycling law, recognizing the strong economic and environmental benefits of recycling.”

Amy Dubruiel is a senior waste management specialist in the DNR’s Waste and Materials Management Program.

Recycling today: ‘So much more than paper’

How far we’ve come and what a difference we’ve made since Wisconsin passed its recycling law 30 years ago. Government and industry leaders in Wisconsin celebrate the importance of the law that’s benefited the state’s natural resources and business interests alike. Here are a few of their thoughts.

DNR Secretary Preston D. Cole: “This anniversary not only marks a milestone, it highlights the fact that for 30 years Wisconsinites have been making a difference by recycling, which in turn benefits the community and the environment. From reducing the amount of waste sent to landfills, saving energy and conserving natural resources such as timber and water, every little bit helps. At the DNR, we are charged with protecting the state’s natural resources, a job we take very seriously. Through recycling, everyone can help protect our natural resources for generations.”

Dave Pellitteri, owner of Pellitteri Waste Systems and member of the Council on Recycling: “Recycling has become ingrained in Wisconsin residents’ way of life. Growth in shipping directly to your home (a.k.a. the ‘Amazon effect’) is causing the volume of recycling within a home to explode. In the past, a home could get by with a large, wheeled cart picked up every other week, but now some municipalities are needing to increase the recycling cart pickup to weekly.”

Meleesa Johnson, Marathon County Solid Waste Director and president of Associated Recyclers of Wisconsin: “Wisconsin’s environmentally progressive history fostered support for the law we now know as the recycling law. Wisconsinites were driven by a deep desire to reduce the need for more landfills and to require that valuable recyclables be diverted into productive use. Today, a statewide network of recycling and waste reduction professionals connect and collaborate to implement not only the statutory provisions of the law, but also carry on with the spirit of the law.”

Julie Anderson, Racine County Director of Public Works and Development Systems and member of the State of Wisconsin Natural Resources Board: “It’s amazing to see how far we’ve come in our knowledge about recycling in the past 30 years. Personally, I like to see overflowing recycling carts instead of overflowing garbage carts. … We have made great strides over the years and now, so much more than paper is recycled in the office! Recycling means conserving our finite natural resources, saving energy and providing economic benefit to various end users.”

Barb Worcester, deputy chief of staff for Gov. Tony Evers and member of the Council on Recycling: “As we celebrate the first 30 years of the recycling program, Wisconsin should be proud of the progress we have made and remind ourselves of the positive impact it is having on making our neighborhoods, our communities, our state and our planet a safer and healthier place in which to live.”

Recycling number system traces roots to Wisconsin

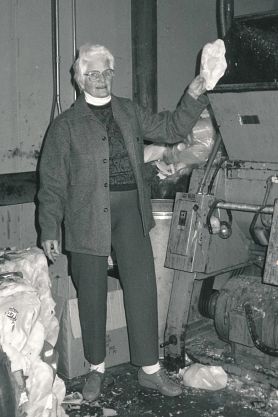

©DORIS LITSCHER GASSERMilly Zantow in 1990

©DORIS LITSCHER GASSERMilly Zantow in 1990The triangle-numbered system has become synonymous with recycling, but did you know the woman who invented it was a Wisconsin native? Longtime Sauk County resident Mildred “Milly” Zantow pioneered the plastics recycling movement and created the numbered system used for identifying different types of plastics.

Zantow, born in Oklahoma in 1923, came to Wisconsin in the 1960s. She got involved with the International Crane Foundation in Baraboo and, during a 1978 trip to Japan with the ICF, became enthralled with that country’s system for sorting waste materials for reuse.

Upon her return home, Zantow learned her county landfill was

closing and there wasn’t another lined up to replace it. Determined to create a plan for the heaps of plastic waste material in the dump, she worked to eliminate a major barrier to recycling — identification.

Zantow’s research on the properties of different kinds of plastics led to her invention of the numbering system we use today. She also started a recycling collection center in Sauk County, worked to spread the word on the benefits of recycling and helped to write Wisconsin’s recycling law, passed in 1990.

Zantow died in 2014. Because of her efforts on behalf of recycling, she was inducted posthumously into the Wisconsin Conservation Hall of Fame in 2017, considered an early “recycling revolutionary.”

Two websites are excellent resources for adults and children

to learn more about Zantow:

- Wisconsin Women Making History - Milly Zantow [exit DNR]

- Wisconsin Biographies - Milly Zantow [exit DNR]

— DNR staff

DON’T TRASH AND BURN

Here’s a look at when certain items were banned from landfill and incinerator disposal in the state:

- 1990 – Lead acid batteries, waste oil and appliances

- 1993 – Yard waste

- 1995 – Newspaper, cardboard, magazines, office paper, steel/bi-metal, aluminum, glass and plastic containers (#1 and #2)

- 1995 – Tires

- 2010 – Electronics

- 2011 – Oil filters