Frequently Asked Questions

Beach Program, Beach Health and Beach Monitoring

Frequently asked questions about beaches are answered on this page.

General Beach Questions

What is a beach?

For the purposes of coastal recreational water quality monitoring, the DNR has defined a beach as "a publicly owned shoreline or land area, not contained in a man-made structure, located on the shore of Lake Michigan or Lake Superior that is used for swimming, recreational bathing or other water contact recreational activity."

When is the beach monitoring season in Wisconsin?

The beach monitoring season runs from Memorial Day weekend through Labor Day weekend each year.

Where can I find a map of beaches in my area?

Maps of public coastal beaches are maintained on the DNR website. You can search for swimming beaches on inland lakes on the DNR website as well.

Who can I call for more information about beach conditions?

You can contact local health departments for further information on beach conditions. Contact information for local health departments can be found on the Wisconsin Department of Health Services website.

Who can I contact with Beach Health questions?

Please contact:

Diane Packett

BEACH Program Manager

Office of Great Waters

608-640-7511

DianeL.Packett@wisconsin.govWhat can I do to stay safe at the beach?

Visit our Beach Safety Tips page for ways to stay safe while you visit Wisconsin's beaches.

What is the BEACH Act?

The federal BEACH (Beaches Environmental Assessment and Coastal Health) Act is an amendment to the Clean Water Act which requires all coastal states, including Great Lakes states, to develop programs for effective water quality monitoring and public notification at coastal recreational beaches.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has made grants available to participating states to develop and implement a statewide beach program. These funds allow communities with Great Lakes beaches to monitor for elevated levels of Escherichia coli (commonly referred to as E. coli), a pathogen that can cause illness if ingested. The monitoring data helps local health officials determine when to close a beach due to unsafe conditions and to notify the public so that beach visitors can make informed choices about swimming at the beach.

How is the Wisconsin beach program funded?

The Wisconsin coastal beach monitoring program is funded by the EPA under the federal BEACH Act. Learn more on the EPA's Beaches pages. Learn more on the EPA's Beaches pages. For questions about funding for coastal beach monitoring, contact Diane Packett.

The DNR funds the monitoring of state park beaches and some local beaches in partnership with local public health departments. For more information about funding for inland beach monitoring, contact Zana Sijan.

How can I make a comment about the beach program?

You can make comments about these webpages or the program in general, as well as provide other input to help improve the program, by emailing DNRBeachHealth@Wisconsin.gov.

Beach Monitoring

How is beach water sampled?

What signs might I find at the beach?

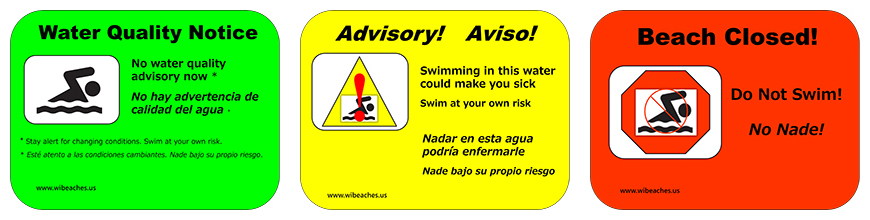

The following signs are intended to inform the public about the most current water conditions based on testing for Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria. The EPA requires that beaches be posted with an advisory sign informing the public of increased health risk when a water sample exceeds 235 colony-forming units of E. coli per 100 milliliters of water.

Beach health signs you may see at swimming beaches. Green is Good, yellow is Caution and red is Closed. Sign designs were approved in 2004 by the beach program's workgroup, which included representatives from local health departments, state agencies and water scientists. The workgroup decided that a blue informational sign shall be posted at all monitored beaches when water tests are below the EPA standard.

Local health departments have the option of posting the green "Good" sign together with the blue sign, if they so choose. Some health departments, against the workgroup's recommendation, have chosen not to post the green sign at all.

The workgroup decided that the yellow "Caution" sign shall be posted when the EPA health standard is exceeded. This sign remains posted until the next daily sample shows the conditions have changed.

The workgroup decided that the red "Closed" sign shall be posted when a water sample shows more than 1,000 colony-forming units of E. coli per 100 mL are present, or under any other conditions that the local health department considers there to be an increased public health risk at the beach. This sign remains posted until the next daily sample shows conditions have improved.

Are all Wisconsin Great Lakes beaches being monitored?

There are about 190 public beaches along Wisconsin's Lake Michigan and Lake Superior coastline. About 106 of these beaches are regularly monitored.

Are inland lakes being monitored?

Yes. All inland state parks monitor their beaches for E. coli at least once a week. Non-state park beaches are monitored at the discretion of local public health officials, who can choose to voluntarily enter data in the Wisconsin Beach Health database.

Why are some beaches monitored more frequently than others?

The priority for beach monitoring was determined after consulting with the public and doing surveys on beaches. The number of people using each beach along with environmental factors were considered. High priority beaches are monitored five times a week, while medium priority beaches are monitored at least two times a week and low priority beaches are monitored once a week or only occasionally. This ranking allows DNR to target limited funds to the most popular and at-risk bathing areas.

E. Coli

What is E. coli?

Escherichia coli (E. coli) is a bacterium commonly found in natural bodies of water. Some strains of E. coli, such as E. coli 0157:H7, are associated with potentially deadly food poisoning. But the strain of E. coli being tested for at coastal beaches in itself poses a low probability of making swimmers ill. Instead, the bacteria serve as an indicator of the possible presence of other health risks in the water, such as bacteria, viruses and other organisms. All warm-blooded animals have E. coli in their feces, which means that if high levels of E. coli are found in beach water there is a high chance of fecal matter being in the water.

What illnesses can occur during an E. coli advisory/beach closure?

Here are some microorganisms that can exist in lake water and examples of the symptoms of illness they can cause in humans.

- Bacteria: Gastroenteritis (includes diarrhea and abdominal pain), salmonellosis (food poisoning), cholera.

- Viruses: Fever, common colds, gastroenteritis, diarrhea, respiratory infections, hepatitis.

- Protozoa: Gastroenteritis, cryptosporidiosis and giardiasis (including diarrhea and abdominal cramps), dysentery.

- Worms: Digestive disturbances, vomiting, restlessness, coughing, chest pain, fever, diarrhea.

If you experience these symptoms or any other signs of illness, it is recommended you seek attention from a health care provider immediately. For more information, see the Centers for Disease Control and Preventions' Healthy Swimming pages.

When there is an advisory or beach closure, is the water safe for pets? For adults vs. kids? For wading vs. swimming?

The EPA E. coli standards are health risk assessments for human health based on data from adults engaging in full-immersion bathing. It is advised that people and pets stay out of the water when the "Caution" or "Closed" advisory signs are posted.

How were the E. coli 235 CFU/100 mL and 1,000 CFU/100 mL standards developed?

The E. coli test results are reported as colony-forming units (CFU) per 100 mL or as most probable number (MPN) per 100 mL, depending on the test used. The traditional membrane filtration tests count “colonies” of bacteria and thus report numbers as CFU. However, the newer defined substrate tests such as Colisure or Colilert report numbers as MPN which is a statistical representation of what level of E. coli is likely present in a sample. For the purposes of reporting, these terms have been used interchangeably.

The following standards were developed for the Great Lakes beaches in Wisconsin and may be used for inland beaches as well.- If the E. coli count is under 235 colony-forming units (CFU) per 100 milliliters (mL) of water, the beach has no advisories or warnings issued.

- If the E. coli count is greater than 235 CFU per 100 mL but less than 1,000 CFU per 100 mL, an advisory is issued.

- If the E. coli count is greater than 1,000 CFU per 100 mL, the beach is closed.

The “Advisory” standard of 235 CFU of E. coli per 100 mL of water was adopted based upon data from three U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) studies conducted in the late 1970s and published in EPA’s Recreational Water Quality Criteria document in 1986 (reference is noted below). These studies indicated that E. coli and/or Enterococci are the best bacterial indicators to assess the risk of acquiring a gastrointestinal illness as a result of using recreational waters.

The epidemiological studies indicated that a level of 235 CFU of E. coli per 100 mL of recreational water corresponds to approximately eight cases of gastrointestinal illness per 1,000 recreational water users.

Wisconsin DNR adopted 1,000 CFU of E. coli per 100 mL as a “Closure” level based upon data from these studies indicating that this represents a risk of approximately 14 cases of gastrointestinal illness per 1,000 recreational water users.

When EPA issued its revised Recreational Water Quality Criteria in 2012, it drew upon additional studies conducted between 2002 and 2007 using new analysis methods and a broadened definition of gastrointestinal illness (reference is noted below). The studies were also conducted in waters impacted by sources of human waste.

Using these more conservative parameters, EPA determined that an E. coli level of 235 CFU per 100 mL corresponds to 36 cases of gastrointestinal illness per 1,000 swimmers. Using EPA’s translation factor for the revised criteria indicates that 1,000 CFU per 100 mL corresponds to roughly 63 cases of illness per 1,000 swimmers.

EPA suggested that an E. coli level of 235 CFU per 100 mL could be used as a beach action value for posting beach advisories based on single water samples, and DNR has adopted this practice.

References- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 1986. Ambient Water Quality Criteria for Bacteria–1986. EPA-440/5-84-002.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2012. Recreational Water Quality Criteria. EPA-820-F-12-058.

- Wymer, L. et. Al. 2012. Appendix A: Translation of 1986 Criteria Risk to Equivalent Risk Levels for Use with New Health Data Developed Using Rapid Methods for Measuring Water Quality. EPA-820-F-12-058.

What is the difference between CFU/mL and MPN/mL?

CFU stands for "Colony Forming Unit" and MPN stands for "Most Probable Number." The traditional membrane filtration tests for bacterial water quality actually count 'colonies' of bacteria and thus is reported as CFU. However, the newer defined substrate tests such as Colisure or Colilert report data as MPN which is a statistical representation of what level of E. coli is likely present in a sample. For the purposes of reporting, these terms have been used interchangeably.

Why E. coli and not Enterococci?

In a 1986 study by the EPA, E. coli levels were found to have the best correlation with highly credible cases of gastrointestinal illness in freshwater systems. While Enterococci had the best correlation in marine (saltwater) systems, either E. coli or Enterococci were deemed acceptable fecal indicators in freshwater systems.

In addition to the EPA studies, the DNR conducted a study prior to the first BEACH season of 2003 in which three state park beaches were monitored for E. coli and Enterococci. The E. coli yielded the most reliable and consistent results in their study.

How applicable are beach water quality results?

The results from E. coli tests can take 18 to 24 hours. It is important to note that an advisory for a given day is based on the results of samples taken the previous day. E. coli levels can also vary from hour to hour and from meter to meter in the lake environment. Consequently, the posted advisory sign may not reflect the actual conditions present in the water.

Getting Involved

What can I do to help the monitoring program?

Keep your eyes open and report any water quality problems you experience at the beach to local health authorities and the DNR. To report problems to the DNR, email DNRBeachHealth@Wisconsin.gov.

What can I do to improve beach water quality in my community?

There are many theories about what causes high levels of E. coli at local beaches. There are steps you can take to help keep our beaches clean and reduce health risks for everyone at the beach. Here are some suggestions to help keep our beaches open.

- Don't swim if you are ill. The virus or bacteria that made you sick can be shed from your body into the water and then into other people who are also in the water.

- Don't feed the birds. This encourages them to unnaturally congregate on swimming beaches as they learn to associate people with food. Waterfowl feces contain bacteria that can make people ill if ingested.

- Properly dispose of all trash, diapers and pet waste in appropriate trash cans if they are available. Pack out all your trash and waste to properly dispose of at home if there are no public trash cans. Take along an extra trash bag to pick up litter you see and dispose of it properly.

- Put swim diapers on babies and toddlers who are not toilet trained before allowing them in the water. Human feces contain viruses and bacteria that can make others sick if ingested.

- Don't swallow lake water and wash hands before eating.

- Don't dump household chemicals or wastes in street drains, as these flow directly into our streams and lakes. Storm drain water does NOT get treated at the wastewater treatment plant.

- Avoid using excess fertilizers or pesticides on your yard or land, as these chemicals are easily carried into our surface waters during rains and snowmelt.

- Report possible sources of contamination to local authorities and the DNR.

- Adopt a beach! (More information below.)

How do I adopt a beach?

Volunteers with the Alliance for the Great Lakes' Adopt-a-Beach program work to keep Great Lakes shorelines healthy, safe and beautiful. Visit their website to either join an existing cleanup event or to start your own beach cleanup project.

Each September, Adopt-a-Beach is part of the International Coastal Cleanup, where people join others in caring for their local shorelines all over the world. Adopt-a-Beach teams will be cleaning up beaches across the Great Lakes. To join in, visit September Adopt-a-Beach: A Great Lakes Day of Action.