Back in the day

DNR owes much of its pictorial history to the affable Dean Tvedt

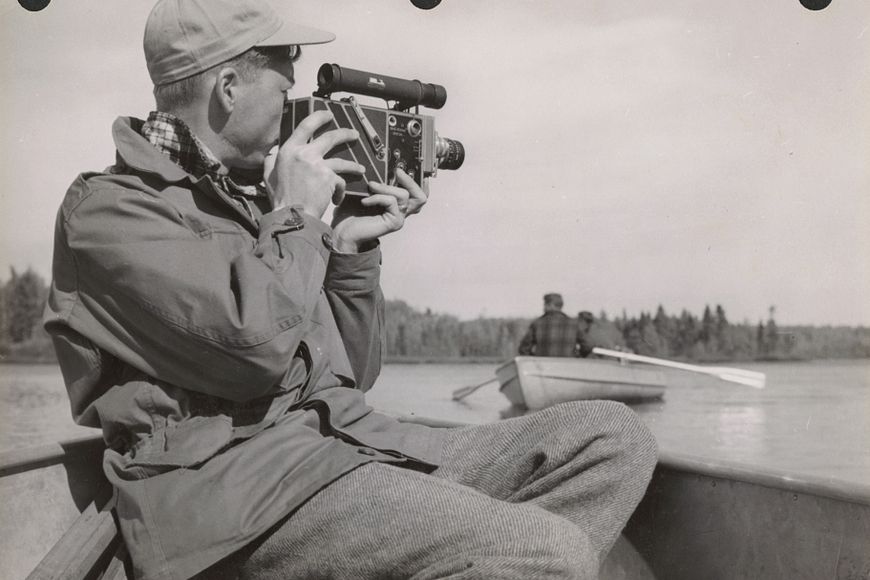

STABER W. REESEDNR photographer Dean Tvedt goes to work on Trilby Lake in Vilas County in 1952. Tvedt died in February at age 96.

STABER W. REESEDNR photographer Dean Tvedt goes to work on Trilby Lake in Vilas County in 1952. Tvedt died in February at age 96.Kathryn A. Kahler

One name that has appeared for decades in this magazine and other DNR publications is Dean Tvedt. His role in documenting Wisconsin’s conservation history is immeasurable, with thousands of photos to his credit. Tvedt died in February at the age of 96.

Tvedt was known to friends for his quick smile and love for reminiscing about his days at the DNR. After retiring in 1987, he could be seen most mornings having coffee with friends at a local eatery near his home in Mount Horeb.

He had nearly perfect attendance at monthly meetings and annual gatherings of fellow DNR retirees. Upon joining the group — formally known as the Association of Retired Conservationists — Tvedt wrote a profile for their website, Association of Retired Conservationists, telling his life’s story.

“I grew up on a farm near Cross Plains where I attended a one-room country school,” he wrote. “Since our farm was the closest to the school, I had the prestigious job of starting the wood-burning furnace each morning during the colder months. Needless to say, I wasn’t very popular if the fire went out before the teacher and other students arrived.

Dean Tvedt

Dean Tvedt“It was at Mount Horeb High School where I joined a camera club and became interested in photography. My first camera had a hole in the bellows and needed to be taped to produce a usable negative.

“There was something about capturing and preserving a moment in time.”

After a photographic job with Commonwealth Telephone Co. and a stint in Japan with the Army Corps of Engineers, Tvedt returned home and got a job with the Wisconsin Conservation Department as a staff photographer.

“We not only produced photos for departmental use, but also 16 mm movies that were used by many schools and conservation clubs around the state,” he recalled.

Television was next. Along with DNR colleagues Wilbur Stites and Staber Reese, Tvedt produced the DNR show “Wisconsin Outdoors.”

EAGLE ADVENTURE

Some of the DNR’s early images reveal scenes from the other side of the camera lens — photographers at work. Surely, Tvedt related countless stories of his filming adventures to his friends and fellow retirees, but little was captured in writing.

Fran Hamerstrom, who with her husband, Frederick, were pioneers in the field of wildlife management in Wisconsin, related one such filming adventure in her book, “An Eagle to the Sky,” first published in 1970.

A chapter called “The Moviemakers” told how Tvedt and Reese once traveled to the Hamerstroms’ central Wisconsin farm in the mid-1960s to film Fran’s rehabilitated golden eagle in pursuit of prey. The DNR film crew agreed to bring “a fox in a box” for prey, and Hamerstrom would have her eagle, Nancy, in “top-notch flying condition for movie day.”

The day of the shoot, Hamerstrom met the five-member movie crew at Buena Vista Marsh, where she had been training Nancy. The area provided the open fields necessary for the shoot.

One of the film crew, Bob Davis, placed the box with the fox where Hamerstrom said Nancy had made her last kill.

“The plan was for me to cast Nancy off and when she reached sufficient altitude and got into good position, I’d give the signal for the fox to be released,” Hamerstrom wrote. “It was breathtaking. Nancy, cast off into the wind, circled, and quickly gaining pitch, came into perfect position.

“Three cameramen, two from car tops, crouched over their cameras, and exultantly I gave the signal. Davis opened the release door. Nothing happened. No fox appeared.

“Nancy made her second swing over the countryside, and at my repeated and rather frenzied signals, Davis started kicking the box. Again, no fox.”

DNR FILESFran Hamerstrom shows off her golden eagle, Nancy, at her farm in Portage.

DNR FILESFran Hamerstrom shows off her golden eagle, Nancy, at her farm in Portage.FOX ON THE RUN

By this time Nancy had stopped flying and was perched half a mile away. Finally, Davis shook the fox box until the animal fell out. More pet than wild animal, it trotted a short distance, then sat down next to a long snowbank.

Nancy slowly flew back in the direction of the fox and repositioned herself nearby “waiting to see what I wanted her to do next,” Hamerstrom wrote.

“It seemed that things had come to a standstill. But eventually the fox took the initiative by wandering over in an offhand manner to sniff Nancy. … When it got uncomfortably close and was almost upon her, she panicked and opened up her six-and-a-half-foot wingspread to take off.

“It is unlikely the fox had ever before seen a stately and almost inanimate object open up like an umbrella. It ran as only foxes can … but after a short and spirited chase the fox took refuge among the people.”

The people, in this case, were “a conglomeration of men, cameras and tripods.” No amount of shouting worked to chase the fox to more open ground for

filming. Still, Tvedt and his fellow crew were not deterred.

“Good moviemen are practical,” Hamerstrom noted. “If they can’t get what they are after, they tend to return with what I believe they call ‘footage.’

“At one point in the proceedings, the fox sat down on an untrampled patch of snow. ‘Hold it,’ called a photographer. We were glad to hold it; we were winded. Even Nancy was panting, and only the fox showed no sign of exertion.

“Tripods and cameras took position and the soft whir of incipient footage could be heard. … A cameraman called, ‘Get it to move.’”

Hamerstrom ran to her car and found “an almost empty bottle of instant coffee” to toss at the fox as an incentive to take off.

“What a charming scene: Fox in sunlight, sitting at rest; coffee bottle flying past his nose missing it by inches; fox getting up slowly and

going over to sniff the bottle.

“It is sad to realize that editorial scissors probably cut this footage.”

TOLD WITH A SMILE

Hamerstrom’s story continued a bit from there, relating the reluctant fox being chased by the dogged camera crew. When the fox found its way into a nearby abandoned shed, a net was retrieved to try to nab the animal in hopes of getting the production back on track.

That was when Frederick Hamerstrom “drove up to see the great fox hunt,” Fran recalled in her book.

“Instead, he was astonished to see a fox shoot around the corner of the shed. It was followed a moment later not by a golden eagle but by … a man with a net who lunged and barely missed the fox, fell headlong in the snow, gathered himself up and took

up the chase again.”

As for Nancy, “she sat on a snowbank,” watching the entire Keystone Cops caper.

“From time to time, some of us helped with the chase, while all the movie cameras stood unmanned, failing to record this episode,” Hamerstrom wrote.

While we don’t know how Tvedt told his side of this story, we’re sure it was with a smile and a twinkle in his eye.

Kathryn A. Kahler is associate editor of Wisconsin Natural Resources magazine. “An Eagle to the Sky” by Frances Hamerstrom is currently out of print, but used copies may be available. Excerpts republished with permission of John Wiley & Sons Inc.; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center. All rights reserved.