Tia Nelson's Time and Place

With Wisconsin as her touchstone, daughter of Earth Day founder continues the cause of environmental activism

EARTH DAY AT 50: EXPANDED COVERAGE

- Environmental awakening

- Tia Nelson, environmental activist and daughter of Earth Day founder

- Apostle Islands National Lakeshore celebrates its own 50th

- 1970 snapshot

- This is the dawning

- Evolution of activism

- Earth Day legacy

- People for the planet: Ways to get involved

- Make every day Earth Day

Andrea Zani

Tia Nelson finds inspiration in regular visits to Governor Nelson State Park, named for her noted father.© ANDY MANIS

Tia Nelson finds inspiration in regular visits to Governor Nelson State Park, named for her noted father.© ANDY MANISOn Jan. 1, as the calendar flipped to 2020, Tia Nelson welcomed the new year as she has so many others before: Spending time at “Papa’s Park,” hiking, relaxing, reflecting and recharging for the busy months ahead.

“It’s my New Year’s tradition,” Nelson says of her annual visit to Governor Nelson State Park, the spot on the shores of Lake Mendota in Dane County that’s named for her father, the late Gaylord Nelson. “I pay my respects, reflect on his legacy and ask him to help me be strong for the cause in the new year.”

Those few hours at the park may have seemed especially important at the start of this particular year, given how busy it promises to be for the daughter of Wisconsin’s 35th governor and three-term U.S. senator.

Gaylord Nelson, who died in July 2005, also was the man behind Earth Day, which is marking its 50th anniversary this year. His legacy as one of America’s leading champions of the environment is front and center as celebrations of the April 22 event gear up worldwide.

With Earth Day’s 50th anniversary looming — and as a career-long environmental proponent in her own right — Tia Nelson has fielded an abundance of requests for media interviews, conferences, speeches, youth projects, event appearances and more. She’s even done voiceover work for an animated Earth Day biography special for PBS Wisconsin.

“They’re giving Gaylord the digital treatment!” she tweeted about the show.

Nelson is accustomed to the spotlight in her role as managing director for climate at Outrider Foundation in Madison and previous work in Wisconsin state government and with The Nature Conservancy in Virginia.

But even she admits this has reached a new level, with a growing spreadsheet required to keep track of the ever-expanding list of Earth Day-related events, not to mention her usual advocacy for environmental issues.

Yet as her father before her, Nelson embraces the challenges and the workload and tirelessly forges ahead, so passionate is she about the issues at hand and so determined to make a difference.

‘Luckiest child in the world’

Two things are quickly apparent in a conversation with Nelson: She is open and approachable, and she is absolutely fervent about matters of the environment. Credit her Wisconsin background and growing up the daughter of Gaylord Nelson for that.

“He has influenced me in any number of ways,” she says of her father, an advocate for environmental reforms at a time when they were little discussed and badly needed. “I am the luckiest child in the world being born Gaylord Nelson’s daughter.”

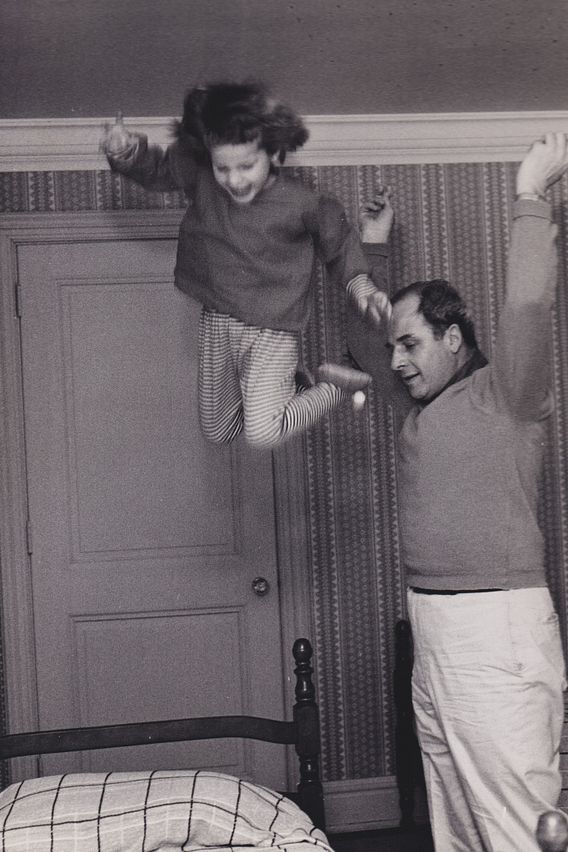

"Papa" to daughter Tia, Gaylord Nelson was a two-term governor and three time U.S. senator from Wisconsin.© COURTESY OF TIA NELSON

"Papa" to daughter Tia, Gaylord Nelson was a two-term governor and three time U.S. senator from Wisconsin.© COURTESY OF TIA NELSONNelson was 2 years old in 1958 when her father, then a state senator, was elected to the first of his back-to-back two-year terms as Wisconsin governor. Born in Clear Lake, Gaylord Nelson was already known for his strong views on protecting the environment.

In office, his work to streamline and solidify the state’s natural resources program plus the creation and funding of the Outdoor Recreation Action Program to acquire land for public parks earned Nelson a reputation as “conservation governor.”

In 1962, Gaylord Nelson was elected to the U.S. Senate and took his family — wife Carrie, sons Gaylord Jr. and Jeffrey, and Tia — to live in Kensington, Maryland, while he served for 18 years in Washington.

As a child, especially when she reached her teen years, Nelson had a front-row seat for the dogged determination her father showed in working for environmental protections.

In an era when such thinking about the environment was only in its infancy, the senator faced often long odds in his efforts to pass the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, for example, or protect the Apostle Islands as a national lakeshore, or encourage a national teach-in on the environment, a.k.a., Earth Day.

Yet he persisted and persevered, Tia Nelson remembers, “continuing on with determination in spite of setbacks and defeats.”

Action for the Earth

As for Earth Day, Nelson notes it was born out of her father’s approach to the environment in the broadest sense of the word. He pushed for civil rights and an end to poverty, believing these issues were part of creating a better overall environment for living.

He also was an early voice of opposition to the Vietnam War and the rising spending it demanded. When anti-war protests began growing nationwide, the senator saw the opportunity to use the same kind of energy to advance the environmental cause.

On April 22, 1970, an estimated 20 million Americans gathered in cities and towns around the country, encouraged by Gaylord Nelson’s idea of a national environmental teach-in. People were taking action for the Earth and demanding their elected officials do the same.

Wearing mirrored expressions, Tia and Gaylord Nelson attend a campaign rally circa 1968.© COURTESY OF TIA NELSON

Wearing mirrored expressions, Tia and Gaylord Nelson attend a campaign rally circa 1968.© COURTESY OF TIA NELSONBecause Earth Day was allowed to develop organically, on the local level rather than planned top-down nationally, it took off, Tia Nelson says.

“The first Earth Day was successful beyond my father’s wildest dreams,” she says. “He couldn’t have imagined the outcome.”

Of course, she adds, “There was no way to know a history-making moment was occurring,” which means she is herself a little fuzzy on what she was doing that first Earth Day.

“I knew you were going to ask that,” she says, remembering she was soon turning 14 and in school at Kensington Junior High School that day.

She relates a story about being on a radio show in recent years and having this same question come up. When she told the show’s host she wasn’t quite sure on the details of her first Earth Day experience, the station took a call.

It was one of her classmates from junior high in Maryland, who told Nelson he knew exactly where she was on that first Earth Day — picking up trash around the school along with him.

“So I was picking up trash,” she says, chuckling at the memory — or lack of it. It was not unlike what kids everywhere were doing that day.

Power of one makes a difference

Nelson marvels at what happened in 1970 and the “environmental decade” that followed, with several milestone environmental laws signed in that and subsequent years. More legislation was passed in the decade after the first Earth Day than at any other time before or since.

The success of Earth Day was a fantastic lesson to her in how the dedication and determination of one person can make a difference. She likens its evolution — with mushrooming grassroots events in communities around the country — to the Civil Rights Movement tracing its beginnings to the humble act of one woman on a city bus.

“Just like when Rosa Parks sat on that bus,” Nelson says, referencing the December evening in 1955 when Parks quietly refused to give up her seat to white riders in Montgomery, Alabama. The ensuing Montgomery Bus Boycott was a watershed event in the Civil Rights Movement.

“Could she have imagined saying one word, ‘no,’ would have made such a difference? She could not have known that.”

As a more modern example, Nelson cites Greta Thunberg, the Swedish teen whose singular protest outside her country’s parliament building eventually inspired young people worldwide to demonstrate on behalf of the environment.

“She couldn’t possibly have known that the simple act of protest would launch a global youth movement,” Nelson says of Thunberg, named 2019 Person of the Year by Time magazine for her role in launching the worldwide School Strike for the Climate.

“No more so than my father could possibly have known.”

Love for Wisconsin’s outdoors

Her father’s dedication to the environment, and her own, are most certainly an outgrowth of their ties to Wisconsin, Nelson says.

“My father grew up canoeing and fishing the St. Croix River,” she says. “It had an impact such that it became a place he worked to protect.”

His advocacy led to passage in 1968 of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, which included Wisconsin’s St. Croix and Namekagon rivers among the original waterways protected.

The Nelson family — from left: Carrie, Tia, Gaylord, Gaylord Jr., and Jeffrey — on a whistle stop tour of Wisconsin during the 1968 U.S. Senate campaign.© COURTESY OF TIA NELSON

The Nelson family — from left: Carrie, Tia, Gaylord, Gaylord Jr., and Jeffrey — on a whistle stop tour of Wisconsin during the 1968 U.S. Senate campaign.© COURTESY OF TIA NELSONMany of her own memories of Wisconsin revolve around summer camp in the 1960s and early ’70s — Camp Hilltop in Spring Green. “I spent every summer in Wisconsin,” she says.

From about age 8 to 17, Nelson attended the all-girls camp in the countryside near Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin, where she learned archery and horseback riding, among other skills, and unleashed her love for the outdoors.

“I cherished those summers,” Nelson says, crediting camp owner Eloise Fritz with being a powerful and positive influence.

“She wanted to nurture us to be strong and fierce. She looked at our hands — you had to have callouses from the hard work. But she still encouraged us to walk and talk like a lady.” Then Nelson jokes, “Maybe the latter didn’t stick as well with me.”

So influential was Eloise and camp summers in those formative years and beyond that “I still dream about her,” Nelson says. “She shaped so many young girls’ lives. I don’t know anyone who went to Camp Hilltop who wasn’t affected.”

Nelson sees that time in her life and Eloise herself “as a touchstone reminder to me of the values she sought to teach us — integrity, hard work, kindness.” Being outdoors in the unspoiled landscape of Camp Hilltop was invaluable to Nelson growing up and remains with her always.

“It’s a reminder of our connection to nature and how important that connection is as part of who we are.”

The Nelsons also returned to Wisconsin from the D.C. area every summer to visit friends in Door County and spend time in “Papa’s favorite place, ” Tia says — the Martin Hanson compound near Mellen, an area now part of the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest.

Hanson, who died in 2008, was a devout advocate for environmental causes and a close friend of Gaylord Nelson. Both are members of the Wisconsin Conservation Hall of Fame.

From DNR to D.C., and home again

Also counting among Tia Nelson’s ties to Wisconsin, going back to the mid-1970s for this, is time spent working for the Department of Natural Resources.

While pursuing her degree in wildlife ecology, she spent summers in Bayfield working as a limited-term fisheries technician. She collected scale samples and recorded lengths and counts for whitefish and trout.

As a college student, Tia Nelson did summer work aboard the DNR's Hack Noyes research vessel on Lake Superior.© DNR FILES

As a college student, Tia Nelson did summer work aboard the DNR's Hack Noyes research vessel on Lake Superior.© DNR FILES“I was the first female to work the Hack Noyes, at least that’s what they told me,” she said of the DNR’s longtime research vessel that traveled Lake Superior.

After graduation, she got a full-time job with the California Department of Fish and Game in the Los Angeles area, collecting fishing data from anglers for creel surveys. Over time, she gravitated toward more of the policy side of natural resources.

Wisconsin was never far from her thoughts, and when Tony Earl — who had been DNR secretary — ran for governor in 1982, Nelson returned “home” to join his campaign. Dan Wisniewski was running the campaign, eventually becoming chief of staff when Earl won the governor’s office, and Nelson was so eager to get back to Wisconsin she told him she’d work for lunch.

“He said, ‘What do you eat for lunch?’ and I said, ‘PB and J,” Nelson recalls. She got the job — and a big PB and J sandwich from Wisniewski. “That was my reward!”

When Earl won the governorship, Nelson worked for about a year in his administration. After that, she went to work with Jeff Neubauer, then a member of the State Assembly. Neubauer (whose daughter, Greta, now serves in the Assembly) chaired the Environmental Resources Committee and Nelson worked as a committee clerk.

“All the environmental laws came through our committee,” she says, including 1983’s crucial groundwater protection legislation.

Being part of the legislative process, especially seeing important laws to fruition, was great experience, she says, and carried her through a few years in the mid-1980s. After that, she headed back to the D.C. area and worked for 17 years at The Nature Conservancy in Arlington, Virginia, before returning to Wisconsin yet again in 2004.

It was about a year later, on July 3, 2005, that her father died at age 88. She gave the keynote remarks in services held for him at the State Capitol.

“You know, he’d never miss an occasion to give you a message, never,” she told the audience crowded into the Capitol dome to pay their respects. “To honor him, I must do the same.”

Environment for everybody

These days, the message for Tia Nelson has landed firmly on the environment, specifically the issue of climate change. She dives right into the topic, speaking in focused and easy-to-follow terms with recurring points of emphasis.

Promoting understanding and developing solutions will rely on how the issue is framed, she says, and progress depends on finding ways to “meet people where they live.”

“It’s a mistake, the idea of using a polar bear as a symbol of climate change,” she says, for example. “Who can really identify with that? It’s about asking, what are your values?

“If you’re an outdoorsman or a fisherman, how are your opportunities for hunting and fishing affected by these changes?”

She pushes the idea that everyone must take stock and understand how climate change affects them.

“There’s the mother who sees her child going through an asthma attack. Clean air will make a difference for that child,” she says. “People need to see climate impacts that are local and relevant to them.”

Seeing the value in resources

Nelson credits her father with being a visionary in getting people to see environmental impacts on a local level and in a broader sense. He regularly spoke about the economic impacts and social nuances of the environment decades ago, before such issues were even fully informed by science let alone acknowledged in the world.

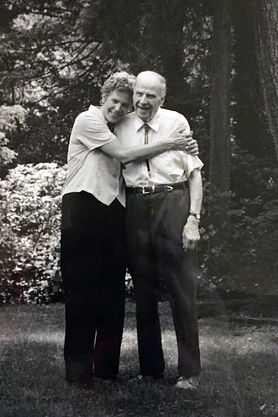

Tia and Gaylord Nelson shared a love for the environment and each other. "Miss you, Papa," she said when tweeting this photo on his June 4 birthday.© COURTESY OF TIA NELSON

Tia and Gaylord Nelson shared a love for the environment and each other. "Miss you, Papa," she said when tweeting this photo on his June 4 birthday.© COURTESY OF TIA NELSON“Fifty years ago, my father framed the environmental challenge through a much broader lens than was embraced at the time,” she says, adding that the same approach is beneficial today.

“We have an opportunity to take stock and recommit ourselves. It requires us to work at every level,” she says. “Individual action matters. How we behave as a community matters. What we ask of our public officials matters.”

Protecting our natural resources, she adds, is a vital part of the process. “You can’t deplete those resources and not recognize you’ve done so.”

Natural resources truly are assets, she continues, “and we’ve got to count them as assets and treat them accordingly.”

Beyond just preaching to the choir

Dozens of references come up as Nelson discusses how various viewpoints can come together on behalf of protecting the environment and the Earth’s resources.

“She mentions the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts, WICCI, which includes participants from the DNR. She talks about the new Loka Initiative, from UW-Madison’s Center for Healthy Minds.

"This initiative involves Muslims, Christians, Jews, Native Americans, Hindus and Buddhists," Nelson says of the project that’s reaching beyond the traditional environmentalist. "It is integrating faith and ecology to create new opportunities for solving big environmental challenges.

“For me, the big challenge in 2020 for those of us thinking of themselves as a conservationist or an environmentalist is: How do we communicate beyond our own echo chamber? How do we communicate beyond the choir?”

In discussing environmental challenges, Nelson moves freely along a historic timeline. At one point, she reaches back to 1856 to make note of Eunice Foote, an American scientist who first drew attention to a warming effect on the Earth created by carbon dioxide gases.

“She was the first to speculate about the greenhouse gas phenomenon” in research more than 150 years old, Nelson says with admiration.

She brings up George H.W. Bush, the first President Bush, recalling how he spoke at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. Bush’s words encouraged “concrete action to protect the planet.” But the moment passed, opportunities were lost.

“We could have done better; we should have done better,” Nelson says. “It’s not easy. It’s complicated and it’s hard.”

Focus on solutions

Nelson mentions someone else in history, too: Nixon. Yes, that Nixon — Richard Milhous — not exactly the first to come to mind on environmental issues. But, as Nelson points out, he did create the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 1970.

Such was the national culture then. And Nixon’s involvement — in addition to starting the EPA, he also signed the National Environmental Policy Act and the Clean Air Act in 1970 — proves you just never know what might happen when you set out to try, she says.

Among more recent references, Nelson speaks of Bob Inglis, a former U.S. Representative from South Carolina who now serves as executive director of RepublicEn.org, which describes itself as “a growing group of conservatives who care about climate change.”

“There’s no more conservative value than to conserve,” Nelson says. “You don’t waste it — whether it’s food or water or energy — you don’t waste it.”

She also speaks of Project Drawdown, which focuses on research to identify climate solutions.

“The top 10 are surprising,” she says, and need not be considered a sacrifice. “No. 3 is reducing food waste. That’s not hard. That’s not a sacrifice. We’ve gotten so that we buy bigger and bigger refrigerators and stuff so much food in there.”

Just do that less, and you’ll cut down on food waste and save money, too, she adds.

No. 6 on the Project Drawdown list also gets her attention: Educate girls. “Who wouldn’t want to do that?”

Lessons to learn, challenges to meet

Nelson’s own education took an interesting twist. As one who struggled in school with a learning disability, she was none too keen on college when the time came.

So what to do? After graduating high school, she announced to her parents she was going to take a year off from school.

“Great,” she recalls her mother saying, then without missing a beat, adding: “And where are you planning to live?”

Nelson — who of late has been a caretaker for her 97-year-old mother still living in Maryland — smiles and remembers what her father did next.

Being from northern Wisconsin, he had a few connections there and put in a call to Tony Wise, an icon in Hayward who owned the Telemark Resort, home of the American Birkebeiner cross-country ski race. At the time, Telemark was a busy and bustling place — just the type of spot that might need help in its crowded restaurant.

“You can be a waitress at a ski lodge, how about that?” Nelson’s father told her.

“I said, ‘Fine, I’m in.’ I earned $1.65 an hour plus tips in the coffee shop at Telemark. Boy, $7 in tips in a day would have been a lot of money then.”

Tia Nelson at Governor Nelson State Park.© ANDY MANIS

Tia Nelson at Governor Nelson State Park.© ANDY MANISShe spent a year working at Telemark before, true to her word, going back to school. She enrolled at UW-Superior — “I thought it might be better to start at a small campus” — which was good for another year.

After that, she took the leap and transferred to UW-Madison, studying wildlife ecology from distinguished professors including department chair Robert McCabe, who’d himself been a student of Aldo Leopold, plus Orrin Rongstad, Joe Hickey and Stanley Temple. All have been credited as dedicated conservationists who made key contributions to state wildlife programs through their work at the university and in the community.

For Nelson, being at the big university meant she had to confront her learning challenges, by then diagnosed as dyslexia, and learn to be successful despite them.

“I think it gave me special powers, in a way,” she says. “I learned people to trust, how to ask good questions. I learned to ask for help with certain tasks.”

Nelson, who is heartened by youth activism for the environment, sometimes speaks to school groups about her own challenges, encouraging them to find their path.

“There are lots of ways of being smart.”

Necessary shift In cultural norms

Admittedly in her current work, Nelson sometimes still feels powerless in her efforts to make headway in addressing critical environmental issues, despite devoting so much of herself to the task. “I feel like a very meek mouse.”

She understands the depth and sweeping nature of the “really significant challenges” at hand.

“Drought, flood, fire, sea level rise — it doesn’t discriminate.”

Yet the sense of perseverance instilled by her father keeps her going, striving to help “establish new cultural norms” when it comes to the environment.

Think about Lady Bird Johnson, she suggests. The first lady during LBJ’s presidency in the late 1960s was a proponent of beautification efforts nationwide.

“Littering — that was in my lifetime,” Nelson says. People would just throw trash right out in the open, and junkyards and waste dumps were commonplace in many an American town. Slowly, though, cultural norms changed.

“We can lead by example,” she says. “We can feel a sense of empowerment. And we can help people shift how they feel.”

Aspire to find solutions

Tackling climate impacts, she says, is about so many pieces, from water quality to “how we produce energy, how we produce our food.” It requires re-examining everything.

Land management also is key, she notes. “It has enormous potential to be part of our solution. Forested lands, native wetlands — these work a lot better to mitigate impacts.”

For about 10 years starting in the mid-2000s, Nelson worked on land management as executive secretary of Wisconsin’s Board of Commissioners of Public Lands. She loved the work but eventually felt politics making the job increasingly difficult so she moved on to Outrider, embracing the chance to advocate for the issues about which she is so passionate.

It’s not so much a call to save the planet, she says — “the planet’s been around for billions of years” — as it is maintaining Earth’s viability and livability.

“We need to secure a planet for humans to thrive and prosper so we’re celebrating the 100th anniversary of Earth Day 50 years from now.”

Nelson circles back to the idea that, in order to find solutions, everyone must come at the challenges from the place they know best.

“There’s something everyone can do to make a difference,” she says. “My point is, you get up, you operate from a place of your values. You do the best you can with what you’ve got, and unimaginable things can happen.”

Andrea Zani is managing editor of Wisconsin Natural Resources magazine.