Masters of Mother Nature

HARDY FLORA AND FAUNA FIND CLEVER WAYS TO ENDURE WISCONSIN'S WINTERS

Christopher Tall and Kathryn A. Kahler

© LINDA FRESHWATERS ARNDT

© LINDA FRESHWATERS ARNDTAs temperatures and snow begin to fall and Wisconsinites settle in for another winter, we take comfort in fireside recliners, hot cocoa and cozy blankets. And, of course, snowblowers. Some of us just throw in the towel, forward the mail and head south to warmer climes.

While they can't don boots or mufflers, our furred and feathered friends have their own special adaptations for toughing out Wisconsin winters.

Birds that don't migrate, like the regal northern cardinal on our cover, weather the winter by fluffing their feathers to trap air, giving them an extra layer of insulation. When food is scarce, cardinals frequent bird feeders where their heavy, cone-shaped beaks help them crack sunflower and safflower seeds, peanuts or cracked corn.

Other physical and behavioral adaptations in birds include specialized beaks for prying seeds from pine cones (crossbills), huddling together for warmth (sparrows), flocking in search of food (grosbeaks and waxwings), putting on fat and extra downy feathers (geese and grouse), shivering to generate warmth (chickadees and titmice), burrowing under the snow (redpolls), and using tree cavities to roost at night (nuthatches and woodpeckers).

Mammals have their own ways of coping with winter. Like birds, some put on fat and add bulk to their coats. Some cache extra food to eat later and huddle in tree cavities or burrows.

Others have specialized adaptations to keep them alive. While in hibernation, black bears recycle their urine to utilize the nitrogen in their blood, guts and liver. This conserves strength and muscle mass and promotes healing from injuries they may have had going into hibernation.

It would take a book to cover the myriad methods our flora and fauna use to survive Wisconsin's harsh winters. We've chosen just a few to highlight here, trying to be detailed but simple enough to understand the often intricate biology behind nature's survival skills.

Along with each capsule, we feature entries from the extensive photo file the magazine has maintained over the years. We invite you to get out and snap a shot or two of how you see nature's winter warriors and send them to us at DNRMagazine@wisconsin.gov.

And should the polar vortex make its way to our state this year, don't forget your polar fleece mittens.

Badger digs in for long naps

The elusive American badger's talent resides in its expert ability to dig. These solitary carnivorous nocturnal mammals have extraordinarily long claws that are dull at the tips, which helps them create a network of up to 980 feet of burrows and dens. This network of tunnels is called a sett and may take years to complete!

© KYLE COKER

© KYLE COKERIn the winter months, badgers waddle down to their sett and enter a state of torpor, a period of about 29 hours where deep sleep slows their metabolism and conserves energy. It can be thought of as a temporary hibernation. They do emerge from their burrows when the temperature rises above freezing.

Before this temporary hibernation, however, a badger needs to hunt for food. A badger's menu might consist of ground squirrels, woodchucks, pocket gophers, snakes, moles, shrews, mice and rats.

Badgers are accomplished hunters and dig into the underground tunnels of their prey, sometimes intentionally covering up the exit routes so their prey cannot escape. During some hunting trips, badgers will work along with coyotes to round up their prey. Coyotes will chase prey into their dens while the badger catches the prey underground. Wildlife ecologists call this behavior mutualism.

During fall, badgers might save some of whatever they catch to eat later. This is called caching and is typically a behavior used in the autumn months to help the badger gain weight for a long, cold winter. Their food is hidden inside burrows and is usually found again and eaten within a few months.

© FRANK SCHEMBERGER

© FRANK SCHEMBERGERCold feet, warm heart?

Have you ever seen ducks standing on a frozen lake and wondered why their feet don't freeze? It turns out they have specially adapted arteries and veins that act as a heat exchange.

The birds' legs are intertwined with arteries carrying warm blood to their extremities, and veins carrying cold blood back to the heart. Heat is exchanged from arteries to veins before the blood reaches the feet, preventing body heat loss while keeping the feet just warm enough to prevent frostbite.

Research shows ducks only lose about 5% of their body heat through their feet. In extremely cold weather, you may see ducks and other birds standing on one foot with the other tucked up under their feathers. This serves as added protection by cutting the surface area exposed to the ice by half.

Deer hunker down in winter coats

At first glance, white-tailed deer may not look well prepared for the bitter cold of winter, yet deer have developed several practical adaptations that help them survive until spring.

In fall, they seek out high calorie food such as fruits and nuts and build up fat reserves in their body. As chilly weather approaches, they shed their summer coats and replace them with thicker undercoats. Their overcoat grows to have darker, longer and hollow hairs called guard hairs that absorb heat from the sun and insulate their body.

© LINDA FRESHWATERS ARNDT

© LINDA FRESHWATERS ARNDTDeer and moose are the only mammals that share this unique adaptation. Deer also have glands in their skin that produce oil, making the hairs in their coat hydrophobic and able to repel water from melting snow.

In winter, deer reduce their activity and hunker down with other deer in stands of coniferous trees like cedar, spruce and fir, which keep their leaves in winter. These stands are called "deer yards" and help provide valuable shelter from wind and snow.

Deer also are browsers, like goats, and aren't dependent on looking under the snow for food. They sustain themselves with a diet of twigs, stems from low-hanging tree branches and saplings.

© JON COSTANZO

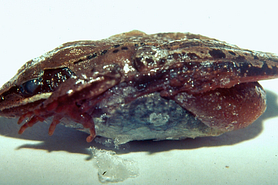

© JON COSTANZOFrog-sicles and skin breathers

Perhaps the most amazing of all overwintering adaptations belongs to amphibians. Some Wisconsin frogs – most notably spring peepers and wood frogs – freeze solid during the winter.

When temperatures start to fall, they insulate themselves in the leaf litter on the forest floor. As their body temperature drops to freezing, their metabolism first speeds up and produces a natural antifreeze, a type of sugar called glycol.

They gradually stop breathing, their hearts stop and brain waves cease. For all intents and purposes, they're dead. Come spring, however, they thaw out and resume their lives.

Other amphibians avoid freezing under the ice of lakes and ponds, where they take in oxygen through their skin and reduce their activity level – although central newts and mudpuppies remain active despite the cold.

The same is true of turtles. Most Wisconsin turtle species spend the winter under ice, where they either bury themselves in the mud or become semi-active by lowering their body temperatures and slowing their metabolism by as much as 99%.

Because they can't come up for air, painted turtles take in needed oxygen through their skin, mouth or cloaca – literally, through their butts! They also break down glycogen, then "borrow" chemicals from their shell and skeleton to counteract the resulting acidosis.

Ruffed grouse igloo

Some wildlife actually benefit from a big snowfall, taking advantage of the insulating value of snow. The ruffed grouse is one such species. It combines a seemingly irrational behavior with a specialized anatomical adaptation to make the perfect winter abode – a grouse igloo!

© JERRY REED

© JERRY REEDThe grouse's winter food supply consists of buds of aspen, poplar, birch, cherry or apple trees. They sit in the tops of trees and can eat enough of the heat-producing buds in a half-hour to sustain them for a day or more. Their large crop – an extension of the esophagus used for food storage – is flexible and can be packed with food to be digested later.

In particularly frigid weather when there's about a foot of powdery snow on the ground, ruffed grouse are known to dive-bomb headfirst into the snow, working their way down until completely buried. The grouse's body heat quickly warms this igloolike shelter several degrees above the air temperature. Provided the snow surface doesn't become crusted, it can hunker down for a few days in its cozy shelter.

Fly on the inside

At the end of summer and into autumn, yellow flowers start to blanket the fields and prairies of Wisconsin. These sturdy plants grow tall and have a strong stem and root system. This plant is called the goldenrod, with a few different species found in Wisconsin.

© CHRISTOPHER TALL

© CHRISTOPHER TALLUnbeknownst to the plant, a small female goldenrod gall fly has spent her time in the spring tasting the plant with chemical sensors in her feet to find a genetically matched plant. She then lays an egg within the stem, and the goldenrod grows around the egg, providing nourishment for the larva after it hatches.

During winter, cold weather triggers the larva living inside the goldenrod stem to convert its glycogen into glycerol and sorbitol, which serve as antifreeze by reducing water content in the body so ice crystals do not form and cause cell injury. This is called rapid cold-hardening (RCH) and is a response in insects that induces protective physiological changes within minutes to hours of exposure to low temperatures.

As winter wanes, rising temperatures prompt the larva to transform into a pupa and finally into adulthood. The goldenrod gall fly – now a winged insect – emerges from its flower stem home through an escape tunnel excavated during the larva stage. Welcome to spring!

© GREG SCOTT

© GREG SCOTTSplitting hares

As its name suggests, the snowshoe hare – occupying mostly the northern half of the state – has specially adapted hind feet with stiff, dense hairs that help it travel on top of the snow. It also changes color from brown to white to camouflage itself in the winter landscape.

Its cousin, the eastern cottontail rabbit, is abundant in the southern half of the state. Both species change their summer diets of grasses and forbs when snow covers the ground. That's when they switch to the tender bark, twigs, buds and needles of a wide variety of trees and shrubs.

In winters with continual snowfall, each snow brings new opportunity to browse, as animals are able to reach higher into the shrubs.

© LINDA FRESHWATERS ARNDT

© LINDA FRESHWATERS ARNDTIncredibly shrinking shrews

Because shrews have a phenomenally high metabolism, they have to eat a lot – some consume two to three times their body weight each day. That means they're active day and night throughout the year.

In winter, they use underground tunnels or grassy runways under the snow to find prey, mostly insects, but also slugs, worms, amphibians and other small rodents. Water shrews, which have specially adapted feet allowing them to walk on water, can trap air bubbles in their fur. They can stay underwater – and ice – to hunt larvae and aquatic prey.

Research in Germany documented an amazing feat that helps common shrews survive the brutal cold – they actually shrink in size. Their spines shorten and major organs, including the brain, shrink by as much as 30%, then rebound in spring.

© LINDA FRESHWATERS ARNDT

© LINDA FRESHWATERS ARNDTSquirrel tales

The eastern gray squirrel is active year-round, but during the winter it's more active midday when the temperature is generally warmer. When the weather is especially frigid, it may seek shelter in a tree cavity or hollow – often excavated by woodpeckers – lined with shredded bark, grass and leaves.

During winter, these squirrels rely on their sense of smell to retrieve acorns and nuts they busily hid and buried throughout late summer and fall.

Though tree squirrels don't hibernate, a smaller ground-dwelling cousin – the thirteenlined ground squirrel – is a true hibernator. It can survive six months of the year asleep in an underground burrow without food or water.

The species packs on weight in autumn to prepare for its long nap. While hibernating, body temperature drops to that in the burrow and heart rate decreases from 300 beats per minute to 10.

Recent scientific studies answer the question, how do these small mammals endure that long without taking even a sip of water? They have evolved a means of suppressing thirst.

Hydration is maintained by hormones that move materials like salt and urea back and forth through the cell walls. In not being awakened by the need to get a drink of water, they are able to stay in their burrow until spring, when body functions return to normal.

Let's hear it for the trees

A common thread in over-wintering in nature is the ability of cells to change composition and structure and produce sugary "antifreeze." The same is true for trees whose winter survival depends on staving off water loss and freezing.

More than 50% of a tree is made up of water – which, in its frozen state, can be deadly to plants and trees. Think of ice crystals as tiny blades that, within a living cell, pierce the cell membrane resulting in death.

© LEN HARRIS

© LEN HARRISTrees in our temperate zone have evolved with adaptations to avoid the killing ability of ice in their veins, basically by reducing or cutting off the flow of water when temperatures fall below freezing.

Broad-leaved deciduous trees – maples, oaks, beech, birch, aspen and the like – drop their leaves each autumn, a process that stems the flow of water in the tree and eliminates the certainty of water loss by freezing in the leaves.

In winter, most of the water in a deciduous tree is stored as sap in the root system, where there's less chance of freezing. The sap that remains in the trunk and branches contains more sugar, which lowers the freezing point of the water.

With maple trees each spring, that sweetness translates into the maple syrup produced when day and nighttime temperatures achieve just the right balance to make sap flow.

© R.J. AND LINDA MILLER

© R.J. AND LINDA MILLEREvergreens such as spruce, pines, firs and cedars have their own set of strategies to deal with the cold. Their needle-shaped leaves have less surface area and are covered with cutin, a waxy substance that also cuts water loss and protects from freezing.

Conifer sap is much stickier, or viscous, than that of deciduous trees and not as susceptible to freezing. Their conductors – called tracheids – are much narrower in diameter, reducing formation of air bubbles that could puncture the vessel walls.

Also, because conifers lose their leaves gradually over several years as older needles dry and brown, they maintain a certain amount of photosynthesis year-round to provide nutrients to the tree.

There are other characteristics of deciduous and evergreen trees that help them weather the extremes of winter.

The conical shape of evergreens prompts heavy snow to slide off branches that otherwise might break from the weight. Similarly, deciduous leaf drop lessens the surface area available for snow and ice to accumulate and cause breakage.

In winter, a tree's bark protects it from temperature variations caused by nighttime lows and daytime highs, especially on frigid, sunny days. This prevents frost-cracking in the trunk and branches.

Though trees are most treasured and appreciated in warmer months when they provide shade, protection and vivid color for human pleasure, they offer untold value to Wisconsin's wintering wildlife.

Their sweet sap provides nutrition to sapsuckers and tree squirrels that nibble maple branches as winter wanes. Thick bark harbors insects that are mined by woodpeckers, excavating cavities that are in turn used by small birds and mammals to shelter from the cold.

Low branches of pines and spruces act as snowy shelters for mammals large and small. And cones clinging at the peaks of these trees are seed havens for small birds throughout the season.

FEED THE BIRDS — AND COUNT THEM TOO!

Studies show that birds benefit from feeders, especially in severe winters when their natural food sources are unavailable. With the number of U.S. households with bird feeders estimated as high as 75%, that's a big boost for birds.

© LINDA FRESHWATERS ARNDT

© LINDA FRESHWATERS ARNDTFatty food sources like safflower, sunflower and suet help a variety of birds put on fat. That allows them to survive winter nights and improves nesting success in the spring.

Winter bird feeding is not only good for birds, it provides hours of enjoyment for birders stuck inside. Hanging a variety of bird feeders – from hoppers and tube feeders to platforms and suet feeders – will assure a diversity of birds in your backyard.

Want to up your game and help scientists track bird populations? It's as easy as sitting at your kitchen window with binoculars and a tally sheet.

Several projects are available for birders to help count birds seen in their backyard or on a winter hike.

- Wisconsin eBird will help you get started with tools for managing lists, photos and audio recordings plus a mobile app for collecting and reporting your sightings. Visit About Wisconsin eBird to learn more.

- Project FeederWatch is run by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and provides information about how to get involved with bird counting, as well as tips for feeding and identifying birds. Visit Project FeederWatch for information.

- Become part of the longest-running citizen science birding project by joining others around the country in the Christmas Bird Count. Visit Audubon Christmas Bird Count and make this Christmas special for the whole family.

- The National Audubon Society invites birders to count birds over a four-day period in February (Feb. 14-17, 2020) with the Great Backyard Bird Count. Visit The Great Backyard Bird Count to learn more.