Lower Rock River basinwide issues

For more information about stormwater management, connect to the Center for Watershed Protection [exit DNR].

- Basin description

-

The Lower Rock River basin in south-central Wisconsin drains an area of 1,857 square miles, all of which lies within the glaciated portion of the state in the southeast upland soil-landform region. The basin is comprised of 15 watersheds, which range in land use from rural-agricultural to intensely urbanized. These 15 watersheds include larger, slow-moving, turbid waterbodies, such as the Yahara River, as well as coldwater trout streams, such as the Rutland branch of Badfish Creek and Spring Creek in the Badfish Creek watershed. Collectively, these waterbodies drain through the mouth of the Wisconsin portion of the Lower Rock into northwestern Illinois, where the Rock River drains into the Mississippi River.

Prior to European settlement, the basin contained thousands of acres of wetlands supporting diverse ecosystems, ranging from shallow wet meadows and prairies, to lowland wet forests, to deep water marshes. A large, undetermined portion of original wetland acreage has been destroyed by agricultural, urban and transportation development, or converted to other uses by filling, ditching and draining. About 47% of the state's wetlands have been ditched, drained, filled or otherwise destroyed in the past 170 years. That percentage of lost and/or altered wetlands is likely much higher here in the southern part of the state than in the north due to intense agricultural and (sub)urban development.

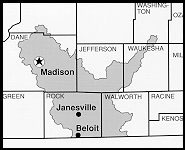

The Lower Rock River basin is bounded at Fort Atkinson on the north and the Wisconsin-Illinois state line in Beloit on the south. Major tributaries include: the Bark River in Jefferson, Waukesha and Washington counties; the Yahara River in Rock, Dane and Columbia counties; and Turtle Creek in Walworth and Rock counties. Small and large lakes -- including Mendota, Monona, Koshkonong, Waubesa, Wingra, Kegonsa, Whitewater and Delavan -- dot the basin's terrain. Most of these lakes are eutrophic and suffer from problems that impair water quality and recreational use. A cluster of high-quality lakes exists in the Bark River watershed, LR13. These lakes are under intense development pressure.

The basin covers about the eastern two-thirds of Rock County, 40% of Walworth County (western edge), the southern half of Jefferson County, about half of Dane County (southeastern) and parts of Waukesha, Washington and Columbia counties. The major cities include Madison, Janesville, Beloit, Fitchburg, Middleton, Sun Prairie, Whitewater and Fort Atkinson.

The Lower Rock basin can be subdivided into three major sub-basins: the Yahara River/Koshkonong Creek Sub-basin, the Bark River Sub-basin and the Turtle Creek Sub-basin:

Subbasin name Watersheds Size - square miles Yahara R./Koshkonong Cr. LR6 - LR12 858Bark River LR11, LR13-LR15 400Turtle Creek LR1 288Watersheds LR02 through LR05 support small tributaries (Blackhawk Creek, Bass Creek and Marsh Creek, respectively) and the Rock River main stem southern reach, for a total of 314 square miles of surface water and land. The basin's most populous areas (in descending order) include: Madison, Monona, Sun Prairie, Janesville, Beloit, Fort Atkinson, Stoughton, Edgerton, Whitewater, Hartland, Delavan and Delafield.

- Water quality problems

-

While urban areas continue to grow, particularly in and around Madison, Janesville, Beloit and Delafield-Hartland, the predominant land use in the basin remains agriculture. Agricultural lands in this basin are among the most productive in the state. This valuable land use comes, however, at an equally valuable cost: drained and altered wetlands; stream channelization; increased runoff carrying soil, nutrients and pesticides to surface waters; and groundwater contamination. In 1991, four counties in the basin ranked among the top 10 counties in the state for their loads of nitrogen due to soil erosion. Jefferson ranked highest in nitrogen loading in the state, followed by Dane (fifth), Rock (eighth) and Walworth (ninth).

The primary sources of the basin's water quality problems are urban and rural polluted runoff. Problems associated with polluted runoff exacerbate one another so that factoring out the cause from the result is at times challenging. For example, excessive populations of rough fish, such as carp, thrive in turbid environments that might be the result of polluted runoff, but also contribute to that turbidity by scouring bottom sediment, resuspending nutrient-laden particles and out-competing other fish that require higher water quality.

Hydrologic modifications such as dams, stream straightening and the ditching and draining of wetlands are significant contributors to lower water quality in the basin. Numerous low-head dams trap nutrient-rich sediment, effectively reducing the stream's depth, increasing water temperature and precipitating algal problems. These types of water resource alterations have complex and reverberating effects on the system's balance, both from a water quality and a ecological balance perspective.

The primary water quality and quantity problems include:

- altered stream and groundwater hydrology;

- continued loss of aquatic and riparian habitat;

- sedimentation of streams, natural lakes and millponds;

- pesticide and nitrate contamination of groundwater; and

- increased quantity and reduced quality of stormwater runoff.

Sources of these problems, as mentioned above, are complex and interactive and are discussed in detail throughout this report. Primary sources include changes in land-use patterns, from low density rural to high-density suburban and the subsequent increase in impervious surface area and alteration of regional hydrology. Also of concern are streambank and cropland erosion; the continued presence of nitrate and pesticides in groundwater; and the continued loss of wetlands and subsequent simplification of fish and aquatic wildlife habitat throughout the basin.

- Land uses

-

A basinwide comparison of current land use to original vegetation indicates a dramatic change in use from presettlement times. In general, the more the change between original vegetation and current land use, the more likely the watershed has conditions that produce nonpoint source pollution. The southern portion of the state was once primarily oak savannah, wet or mesic prairie and wet forests, reflecting the Native American practice of burning prairies, stochastic events (fires from lightning or floods) and the Wisconsin glaciation, which left vast tracts of wetlands and lakes in its wake.

Percent of different land uses in the basin Urban 7.5% Cropland/pasture 79.5% Forest 4.6% Lakes/reservoirs 3.5% Wetland 4.2% Prairie na Barren .7% Land uses today

Today the basin is comprised primarily of agricultural land (the productivity of which can be attributed to rich, fertile soils left behind by the pleistocene glaciation) and urban and suburban residential centers (Madison, Janesville, Beloit, Stoughton, Whitewater, etc.). While major urban centers have thrived for some years and continue to grow, outmigration from these central urban regions is becoming more prevalent. Urban sprawl, or outmigration from the city to the suburbs, is now a major land-use issue in the state and a cause for concern among state and local governments and many residents.

Between 1990 and 1994 the state's population grew by nearly 1% per year but most of this growth is concentrated at the urban fringe. Also, the average household size has been dropping steadily, from 3.4 people per household to 2.6 per household in 1994, which means that the average number of homes per acre is going down, increasing the demand for land (State Interagency Land Use Report, 1995). Individuals are more willing to commute longer distances to work to enjoy living in rural areas or outlying suburbs. This shift in work/residence location patterns is widespread and accounts for losses of prime agricultural land, wetlands and other open spaces in the basin, particularly in the Madison/Stoughton, Janesville, Beloit and Ft. Atkinson areas.

Construction of large-scale residential, commercial (e.g., mega-shopping malls) and industrial complexes at the edge of metropolitan areas fosters the outmigration the urban populace, which negatively affects the city's economic, social and cultural health.

Environmental consequences include increases in impervious surfaces and the resulting hydrologic modifications - increased water quantity via increased stormwater runoff to waterbodies by development of shorelines, loss of naturally vegetated recharge areas and urban/suburban stream ditching and channeling. Hydrograph flashiness (see below) is greatly enhanced. Stormwater quality is negatively affected by increased vehicular use (e.g., the resulting emission of nutrients and leakage of oil, grease, gasoline and heavy metals), increased number of homes using fertilizers, pesticides and septic systems (perhaps) and increased numbers of pets contributing animals waste. Construction site erosion is a major source of suspended solids and nutrients, which clog stormwater drains and urban streams, transforming them into turbid, silted muckways incapable of supporting healthy aquatic life.

- Hydrology

-

A stream hydrograph is useful to biologists because it shows changes in streamflow over time. Dry weather stream base flow includes flow generated from groundwater discharged to the stream, which may be augmented by discharges from wastewater treatment plants or impoundments. The level of base flow for some streams is zero because flow only occurs during precipitation. Other streams have year-round base flow from groundwater discharge from seeps or springs. Peak flows are levels of streamflow recorded during storms when surface runoff contributes to the existing streamflow.

Land use that promotes over-land runoff rather than infiltration of precipitation has been shown to greatly affect hydrographs. A sudden increase in flow may be associated with flash flooding on some streams. The energy of this peak flow is dissipated by thrashing action against streambanks, which may result in streambank erosion, especially along trampled and/or poorly vegetated banks. In-stream habitat is also disturbed by high peak flows, which often carry sediment that eventually settles to cover "clean" substrate needed by fish and aquatic insects.

The topography of the Lower Rock River basin affects the hydrography of its streams; low gradient streams with abundant springs and wetlands are less easily drained than the undulating hummocks of terminal moraines and outwash plains. Land use is a major factor in both of these settings. Enhanced overland runoff from rapid increases in impermeable land cover affects the stability of stream channels. Rapid onset of storms coupled with a flashy hydrograph can result in severe damage to a stream's riparian and in-stream habitat. An unstable stream channel will continually erode its banks until it reaches equilibrium. By improving infiltration throughout the watershed, the stream achieves a more gradual increase in flow coupled with lower peak flows during storms results in less overall stress to the stream channel and aquatic habitat.

- Streamflow trends and gauge stations

-

Wisconsin has a network of streamflow gauging stations maintained by staff from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Trend analysis of stream flows is not possible without continued funding to keep gauging stations functional. Documentation of stream flows is critical for assessing trends that may link decreased peak flow and increased baseflow with improved water quality and in-stream habitat. Stream gauge station data is also necessary for calculating nutrient and other pollutant loading rates in streams with accompanying water quality data. USGS gauge stations recently discontinued include stations on the Rock River at Indianford (water year 1975) and Afton (water year 1914) and on Turtle Creek near Clinton (water year 1939) and on the Yahara River at McFarland. The result of no or inaccurate data on streamflow can result in the following problems:

- Over or under design of flood peaks and bridges;

- Floodplain areas over- or underestimated;

- Under- or overestimation of low flows and over- or under-design of sewage treatment plants;

- Reduced accuracy of sediment load and flushing rate estimates.

Wisconsin DNR should continue its financial support of the remaining gauging stations throughout the Lower Rock River basin. In particular, the Rock River-Afton Station is critical for obtaining flow and water quality trend monitoring data (STORET station number 543001, USGS gauge station number 5430500). The Afton flow gauge needs to be assured stable funding since it is a key station for the basin. Rock County has helped fund the continuation of this station, but its future should be secured from a stable long-term source (Dale Patterson, Wisconin DNR, 1996).

Management recommendations

- Wisconsin DNR should form partnerships with others to continue funding to maintain USGS gage stations in the Lower Rock River basin (type b).

- Wisconsin DNR and partners should continue funding the Rock River basin Afton gage station to obtain flow and water quality tend monitoring work (storet station number 543001, USGS gage station number 5430500) (type b).

- Benefits of infiltration to streams

-

In 1992, James Knox and Douglas Faulkner of the University of Wisconsin-Madison studied the Lower Buffalo River in Wisconsin's Driftless Area to determine the source and reason for sedimentation at the mouth of the Buffalo River. Some of the study findings can be applied to streams statewide. The study findings included the following.

If widespread conservation practices that reduced upland erosion were implemented, sediment delivery to the mouth of the river may be reduced.

The reduction of upland sources of erosion without a complementary reduction in stormwater quantity to the river and its tributary streams may actually increase mobilization of existing sediment in the channels. Since stormwater would reach streams without an upland sediment load, the water would have a greater ability to mobilize sediment stored in stream channels.

Managing the rate of runoff and upland erosion would benefit the river and its tributaries. By allowing stormwater to recharge groundwater instead of running off into streams, two goals are accomplished: 1) the baseflow of tributaries to the river is increased from the groundwater recharge and 2) damaging peak flows are reduced.

Increasing tributary baseflows via infiltration lowers the stream temperature and increases stream volume during low flow periods; both of these actions enhance coldwater species survival. Reducing the volume of peak flows reduces the magnitude and number of damaging flows that destroy fishery habitat and incise stream channels that move sediment downstream.

These management implications are applicable to the Lower Rock River basin's rolling topography, found throughout the morainal regions of Dane, Rock and Jefferson counties. Directing stormwater to groundwater will benefit streams with fishery potential and reduce sediment movement through the system. Best management practices that increase or maintain infiltration will help improve stream water quality and in-stream habitat.

Recommendations

- Wisconsin DNR should form partnerships with others to continue funding to maintain U.S. Geological Survey gauge stations in the Lower Rock River basin (type b).

- Wisconsin DNR and partners should continue funding the Rock River-Afton gauge station, the Yahara River-McFarland gauge station and Pheasant branch and Yahara River (Windsor) gauge station to obtain flow and water quality trend monitoring work (type b).

- Urban runoff

-

Urban polluted runoff is a problem in many parts of the basin, particularly in the Madison, Janesville, Beloit, Stoughton and Sun Prairie areas and in developing areas around lakes in Jefferson, Walworth and Waukesha Counties (e.g., the Bark River watershed). Polluted urban runoff takes two general forms: stormwater running off impervious surfaces such as rooftops, parking lots and streets, carrying sediments, nutrients and other pollutants; and sediment-laden water flowing from development sites into streams and lakes.

- Characteristics of stormwater

-

Rainfall and snowmelt runoff is a major problem for surface water quality in many developed areas. Runoff from surfaces such as parking lots, streets, rooftops and material storage yards as well as from lawns, is also a major source of pollutants reaching surface water and groundwater. In urban and suburban areas, a large percentage of land in developed areas is covered by impervious surfaces such as buildings and pavement, which collect and channel pollutant-laden stormwater. Principal water quality problems for the basin's urban streams are the result of the following factors:

- stream channel modifications, including straightening and lining with concrete

- high loading of pollutants including sediment, nutrients, bacteria, heavy metals and other toxic materials

- hydrologic disturbances, including flashy high flows and loss of base flow

- streambank erosion due to flashy high flows

Studies conducted in Madison, Milwaukee and Eau Claire documented levels of metals, suspended solids and nutrients in stormwater effluent that exceed some in-stream water quality standards for stormwater runoff effluent. Stormwater runoff is a definitive source of pollutants that can be a significant cause of surface water quality degradation.

USGS conducted stormwater monitoring in seven drainage basins in the city of Madison from April 1993 through November 1994 (USGS). Seven different urban land uses were analyzed for inorganic and organic constituents. The data illustrate the flushing action of spring rains into waterways from urban areas, particularly industrial, high-density residential, highway and shopping center (parking lots) land uses.

Generally, the highest level and most frequent occurrences of total zinc were in industrial, light industrial, highway and shopping center (parking lot) land uses. The few instances in which semi-volatile organics occurred at levels higher than the limits of detection took place in industrial, high-density residential, highway and shopping center land uses in March through May. The level of total phosphorus in stormwater peaked in the high-density residential area (2.38 mg/l) in November 1993, while generally, the level of total nitrogen in stormwater was consistently higher in the high-density residential and university stormwater samples.

Regulation of stormwater

The management and regulation of stormwater is divided among federal, state, county and local governments, depending on the land's status of incorporation and size and the activities affecting stormwater on the land.

- Municipal stormwater

-

Under Phase I regulations at the federal level, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) requires municipalities with populations of 100,000 or more to obtain coverage under a municipal stormwater discharge permit to control the discharge of pollutants. Phase II federal stormwater regulations require municipal stormwater discharge permits for certain municipalities with populations of less than 100,000. In Wisconsin, EPA has delegated the authority to administer comparable stormwater regulations to Wisconsin DNR. Under Chapter NR 216, Wis. Admin. Code, the following municipalities are required to obtain coverage under a municipal stormwater discharge: Madison; Milwaukee; municipalities in the Great Lakes Areas of Concern (Green Bay, Allouez, Ashwaubenon, DePere, Marinette, Sheboygan and Superior); municipalities in a priority watershed that have a population of 50,000 or more (Eau Claire, Racine, West Allis and Waukesha) and other municipalities identified by Wisconsin DNR that meet certain criteria for permitting in section NR216.02(04). Milwaukee and Madison, including the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus, have obtained municipal stormwater discharge permits from the Wisconsin DNR (Bertolacini).

To address flooding and control water quantity, the Federal Emergency Management Authority (FEMA) requires municipalities to perform floodplain mapping and management plan development to receive federal flood insurance.

Regulation of stormwater at the local level is generally confined to developing plans that "detain" water at some predetermined level -- before development occurs -- during the plat review and permit approval process. This local regulatory action takes place through voluntary ordinance development and its effectiveness hinges on enforcement, which requires resources and expertise in a time of diminishing public funds. Further, while site-specific management helps with localized flood impacts and erosion, working within a larger picture, through comprehensive planning, is a more effective water management strategy.

- Industrial stormwater

-

Under NR 216, discharges of stormwater from certain facilities require coverage under an industrial stormwater discharge permit. The owner or operator of the permitted industrial facility is required to develop and implement a site-specific stormwater pollution prevention plan. The plan must be designed to ensure that there are practices in place to reduce exposure of industrial materials to stormwater, such as good housekeeping, spill prevention and cleanup and structural and non-structural controls.

- Construction site erosion controls

-

As land is developed and disturbed, sediment moving off-site can be significant unless proper erosion control measures are implemented. In the Lake Mendota priority watershed (which includes the Yahara River-Lake Mendota watershed (LR09) and the Six Mile and Pheasant branch Creeks watershed (LR10)) construction sites account for only .5% of the total land use in the watershed, but contribute 24% of the total sediment and phosphorus loading to Lake Mendota from all land uses (Wisconsin DNR 1997).

Regulation of construction site erosion falls under several different programs in the state of Wisconsin. Locally, municipalities are required to adopt and enforce the Uniform Dwelling Code (UDC) under a program administered by the Department of Commerce. The UDC contains provisions to control erosion during construction of one- and two-family dwellings. Implementation of the UDC erosion control provisions is only as effective as the local municipality's willingness and ability to enforce the provisions. Oversight of a municipality's effectiveness at administering the UDC is handled by the Department of Commerce.

Larger construction sites involving land-disturbing activities affecting five or more acres are regulated by WDNR's Chapter NR 216, or equivalent programs administered by the Department of Commerce or the Department of Transportation. NR 216 requires a landowner of a larger construction site to obtain coverage under a construction site stormwater discharge permit. The landowner is required to ensure that a site-specific erosion control plan and stormwater management plan are developed and implemented at the construction site.

Typical sites regulated by Wisconsin DNR include residential subdivision development, industrial and business park development, parks and golf courses and private, local and county roads. Through state statute and interagency agreements, regulation of erosion control at larger commercial building sites is administered by the Department of Commerce and state-administered highway and transportation projects, regardless of size, are handled by the Department of Transportation through Chapter TRANS 401, Wis. Adm. Code (Bertolacini).

The jurisdictional overlap and division of regulatory responsibility between Wisconsin DNR, Department of Commerce, Department of Transportation and local governments regarding erosion control have grown complex. Two areas that currently fall between the 'cracks' of erosion control include 1) erosion from construction sites that do not include a one- or two-family dwelling and disturb less than five acres and that are not regulated by a voluntary municipal or county ordinance; and 2) erosion from non-Department of Transportation road and bridge construction that disturb less than five acres and that are not regulated by a voluntary municipal or county ordinance.

Currently, there is no state-level mechanism to address the first category. The Department of Commerce has been given the authority by state statute to develop a uniform commercial building code for erosion control regardless of the size of the commercial development, but this code has not yet been promulgated. As for the second category, Wisconsin DNR and the Department of Transportation have a joint Memorandum of Understanding that addresses water quality impacts during construction of Department of Transportation-administered projects, typically state and interstate highway construction. Under the agreement, these transportation projects administered by the Department of Transportation must have an erosion control plan that is implemented throughout the construction period. Many small-scale transportation projects funded with local money are not, however, required to implement erosion controls. Local ordinances passed by a county, city, village or town are currently the only tools to protect water resources under these circumstances.

Phase II stormwater regulations that are now being proposed by the EPA would, however, drop the acreage threshold down to one acre for a construction site requiring coverage under a stormwater discharge permit. Consequently, like other states with delegated authority from the EPA to administer the stormwater discharge program, Wisconsin will need to modify its regulator program to address these smaller construction sites if the mandate survives at the federal level (Bertolacini).

Currently, Dane, Walworth and Waukesha Counties have construction site erosion control ordinances in place that go beyond the uniform dwelling code requirements, while Jefferson and Rock counties do not have countywide ordinances. In 1997, Jefferson County Zoning turned down a proposal to adopt such an ordinance. Rock County's Land Conservation Department hopes to develop and adopt a countywide erosion control ordinance in the next two to three years. Rock County has gone so far as to offer to enforce existing erosion control provisions for local building inspectors to ensure that the UDC provisions were enforced; the county received minimal to no response.

But even the effectiveness of existing erosion control provisions is not known. Observations by Wisconsin DNR staff and a 1989 report completed for the Dane County Lakes and Watershed Commission (Seyfert) indicate that local control of erosion in Dane County has room for improvement. Observations in Dane County range from no erosion control measures at major development sites to inadequate or improperly installed management practices (i.e., silt fences apparently only serving to mark the limits of the projects). At other sites poor or nonexistent follow-up maintenance measures were implemented.

While some developers genuinely attempt to control erosion, others have not initiated effective controls. The need for heightened awareness about the consequences of and laws relating to, erosion control is evident. A better understanding of problems associated with construction site erosion by developers and contractors, coupled with improved enforcement of existing ordinances by local government, should be a priority.

During the past few years, UW-Extension has held a series of workshops on construction site erosion control for developers and contractors. The workshop series outlines the major features of the Wisconsin Construction Site Best Management Practice Handbook (PUBL-WR-222 92 REV). Community ordinances should remain consistent with current administrative rules and the model ordinance provided in the handbook.

Section 281.33 of the Wisconsin Statutes (formerly Chapter 144.266 Wis. Statutes) gives municipalities the option of enacting local construction site erosion control and stormwater management plans. In Dane County, 23 of the 27 cities and villages have an erosion control ordinance. The problem is not with the ordinances, which could have more teeth to encourage better compliance, the problem is with enforcement. Possible reasons for lack of enforcement include too few resources; inadequate staff, training or knowledge; and fragmented responsibility and authority for administration and enforcement.

- Stormwater management planning

-

The thorough nature of comprehensive stormwater planning implies long-range and geographically broad consideration of flows and water quality during and after the development of major land parcels, such as highways, industrial parks and residential neighborhoods. With few exceptions, maintenance of pre-development hydraulics is most desirable. The large-scale nature of comprehensive planning allows the integration of resources to reach multiple regulatory and management goals, such as those of FEMA, NR 216, sewer service area planning, local water management regulations and even management for aquatic and terrestrial wildlife.

Few municipalities in the Rock River basin have initiated comprehensive stormwater management planning -- yet three in the Yahara-Mendota watershed (LR09) have done so: the village of DeForest (planning completed), the city of Sun Prairie and the village of Waunakee. Also, the cities of Madison and Middleton have ordinances for retention of stormwater from development areas that apply to sites other than and including parcels covered under the Uniform Dwelling Code (UDC).

For example, the city of Middleton's Water Resources Committee has developed an ordinance that requires developers of new parcels to have peak flows to be equal to or less than the original (pre-settlement) vegetation at the site (i.e., before agricultural use of the land). Civil divisions that are not involved in a priority watershed program but that need comprehensive stormwater management planning include Janesville, Evansville, Beloit, Clinton, Whitewater, Fort Atkinson, cities in Waukesha County and Madison's unincorporated areas outside of priority watershed projects. These are only the larger municipalities. A number of rapidly growing cities, villages and towns should also embark upon a planning process for stormwater quality and quantity (see Table 2).

Further implementation of the municipal stormwater discharge permit program under NR216 and the final Phase II regulations promulgated by the EPA will require some municipalities that meet certain criteria to obtain municipal stormwater discharge permits and to develop comprehensive stormwater management programs.

- Municipalities in the Lower Rock River basin and stormwater/erosion control measures in place

-

Municipality W/S No. County Pop. (1995)t Percent growth

'90-'95Stormwater plans and/or ordinances Erosion control ordinances C. Madison LR08, LR09, LR10 Dane 199,518 4.59 NR216, ordinance in place, site-specific planning NR216, ordinance in place, needs updating C. Janesville LR02, LR03 Rock 56,141 7.53 planning needed, subdivision ordinance in place recommended C. Beloit LR01, LR03 Rock 35,891 .90 plan, ordinance recommended recommended C. Sun Prairie LR12 Dane 17,426 13.51 plan in place, ordinance recommended ordinance in place C. Fitchburg LR08 Dane 17,266 10.34 subdivision ordinance in place, site-specific planning subdivision ordinance C. Middleton LR10 Dane 14,818 7.49 subdivision ordinance in place, site-specific planning subdivision ordinance in place C. Whitewater LR14 Jefferson Walworth

13,183 4.33 plan, ordinance recommended ordinance in place C. Fort Atkinson LR11 Jefferson 10,604 3.83 site-specific stormwater reviews; planning, ordinance recommended city enforces UDC for commercial construction projects & multi-dwellings; citywide ordinance recommended (beyond UDC requirements) C. Stoughton LR06 Dane 10,114 15.11 plan, ordinance recommended ordinance in place C. Monona LR08 Dane 8,548 -1.03 plan in place ordinance in place V. Hartland LR13 Waukesha 7,585 9.83 plan, ordinance recommended ordinance in place V. Waunakee LR10 Dane 7,219 22.42 plan, ordinance in place ordinance in place T. Beloit LR03 Rock 6,923 2.14 plan, ordinance recommended ordinance recommended T. Delafield LR13 Waukesha 6,809 18.73 plan, ordinance recommended County ordinance in place C. Delavan LR01 Walworth 6,653 9.55 plan, ordinance recommended ordinance recommended T. Madison LR10 Dane 6,627 2.87 plan in place County ordinance in place Ch.14 C. Elkhorn LR01 Walworth 6,229 16.69 plan, ordinance recommended ordinance in place V. DeForest LR09 Dane 5,976 22.41 plan, ordinance in place ordinance in place C. Delafield LR13 Waukesha 5,944 11.17 plan, ordinance recommended ordinance in place V. Oregon LR07 Dane 5,760 27.46 plan, ordinance recommended ordinance in place V. McFarland LR06LR08 Dane 5,736 9.63 subdivision ordinance in place subdivision ordinance in place T. Dunn LR08 Dane 5,417 2.71 plan, ordinance recommended County ordinance in place Ch. 14 T. Windsor LR09 Dane 4,978 7.75 plan, ordinance recommended County ordinance in place Ch.14 C. Milton LR04, LR11 Rock 4,814 8.33 plan, ordinance recommended ordinance recommended T. Delavan LR01 Walworth 4,417 5.29 plan, ordinance recommended ordinance in place C. Edgerton LR11 Rock 4,385 3.08 plan, ordinance recommended ordinance recommended T. Middleton LR10 Dane 3,968 9.37 plan, ordinance recommended County ordinance in place Ch. 14 T. Cottage Grove LR06 Dane 3,808 8.03 plan, ordinance recommended County ordinance in place Ch.14 T. Janesville LR02 Rock 3,399 8.91 plan, ordinance recommended Countywide ordinance recommended T. Burke LR08 LR09 Dane 3,175 5.83 plan, ordinance recommended County ordinance in place Ch.14 T. Westport LR08 Dane 3,105 13.65 plan, ordinance recommended County ordinance in place Ch. 14 T. Koshkonong LR11 Jefferson 3,097 3.79 plan, ordinance recommended Countywide ordinance recommended T. Fulton LR06 Rock 3,018 5.27 plan, ordinance recommended Countywide ordinance recommended T. Oregon LR07 Dane 2,848 17.30 plan, ordinance recommended County ordinance in place Ch.14 T. Pleasant Springs LR06 Dane 2,840 6.77 plan, ordinance recommended County ordinance in place Ch. 14 V. Marshall LR12 Dane 2,628 12.84 plan, ordinance recommended ordinance in place T. Turtle LR01 Rock 2,463 .20 plan, ordinance recommended site-specific work in priority watershed T. Harmony LR04 Rock 2,262 5.80 plan, ordinance recommended Countywide ordinance recommended T. Dunkirk LR06 Dane 2,155 1.60 subdivision ordinance in place ordinance in place T. Bristol LR06 Dane 2,108 14.88 plan, ordinance recommended County ordinance in place Ch.14 T. Blooming Grove LR08 Dane 2,085 .29 plan, ordinance recommended County ordinance in place Ch.14 T. Sullivan LR13 Jefferson 2,022 5.09 plan, ordinance recommended Countywide ordinance recommended T. Sun Prairie LR12 Dane 2,016 9.62 plan, ordinance recommended County ordinance in place Ch.14 V. Cottage Grove LR06 Dane 1,929 70.56 plan, ordinance recommended ordinance in place V. Deerfield LR12 Dane 1,747 8.04 plan, ordinance recommended ordinance in place T. Rutland LR07 Dane 1,715 8.27 plan, ordinance recommended County ordinance in place Ch.14 V. Walworth LR01 Walworth 1,701 5.39 plan, ordinance recommended Countywide ordinance inplace T. LaGrange LR15 Walworth 1,698 3.35 plan, ordinance recommended County ordinance in place V. Palmyra LR15 Jefferson 1,682 9.22 plan, ordinance recommended Countywide ordinance recommended V. Shorewood Hills LR09 Dane 1,652 -1.67 plan, ordinance recommended ordinance recommended T. Darien LR01 Walworth 1,514 1.61 plan, ordinance recommended County ordinance in place T. Richmond LR01 Walworth 1,487 5.84 plan, ordinance recommended County ordinance in place V. Dousman LR13 Waukesha 1,471 15.19 plan, ordinance recommended ordinance recommended T. Whitewater LR14 Walworth 1,434 4.06 plan, ordinance recommended County ordinance in place T. Walworth LR01 Walworth 1,418 5.74 plan, ordinance recommended County ordinance in place V. Maple Bluff LR09 Dane 1,356 .03 plan, ordinance recommended ordinance recommended T. Deerfield LR12 Dane 1,324 12.11 plan, ordinance recommended County ordinance in place Ch.14 V. Darien LR01 Walworth 1,295 11.83 plan, ordinance recommended ordinance recommended T. Medina LR12 Dane 1,192 6.05 plan, ordinance recommended County ordinance in place Ch.14 V. Cambridge LR11 Dane, Jefferson 1,034 7.37 planning in process ordinance in place T. Cold Spring LR14 Jefferson 716 4.83 plan, ordinance recommended Countywide ordinance recommended V. Dane LR10 Dane 698 12.40 plan, ordinance recommended ordinance in place (t) Population data from the Wisconsin Department of Administration, 1996.