Snapshot Wisconsin June 2023

Ecologist Neil Gilbert used Snapshot data to study wildlife behavior, using trail camera images to dive "behind the scenes" and learn more about animal activity that is otherwise difficult to observe. He recently published his findings in two journals, which can now be viewed with other Snapshot-related publications on the new Scientific Publications page!

Last fall, the Snapshot team asked volunteers for help locating bear dens for the Black Bear Litter and Diet Survey conducted by our colleagues in the DNR's Office of Applied Science. The survey collects valuable data to estimate vital reproductive values for black bears, such as litter size, cub survival rates and litter frequency. A family of Snapshot volunteers answered the call and got the experience of a lifetime assisting scientists with the den survey!

Powering Research: Snapshot Data In Recent Wildlife Behavior Publications

Ecologist Neil Gilbert used Snapshot data to study wildlife behavior. Gilbert's most recent publications can now be found on the new Scientific Publications page and other publications powered by Snapshot data.

Snapshot Wisconsin's Call For Bear Den Reports

The Schiebenes family reported a bear den near their cabin in Marinette County and had the unique chance to help DNR scientists with the den survey.

Powering Research: Snapshot Data In Recent Wildlife Behavior Publications

Snapshot Wisconsin has grown immensely since going statewide in 2018. Millions of photos have been classified, thousands of volunteers monitor Snapshot trail cameras around Wisconsin, and Snapshot data has been used in over 19 scientific publications. One of the researchers that have used Snapshot data is ecologist Neil Gilbert. Gilbert has been integral in using Snapshot Wisconsin trail camera data to study wildlife behavior in numerous scientific research papers, with two of those papers discussed here.

Gilbert is working on his post-doctoral research at Michigan State University, using advanced statistical methods applied to wildlife data and developing new models for combining multiple types of survey data.

The Snapshot team met with Gilbert and Jen Stenglein, DNR Quantitative Research Scientist with Snapshot Wisconsin, to discuss Gilbert's work using Snapshot trail camera data. Thank you to Neil Gilbert and Jen Stenglein for taking the time to talk about this impactful research Snapshot Wisconsin data has contributed to.

"Eating Dirt"

Like many people involved with natural resources, Gilbert spent lots of time outside in his youth and as he described, found himself "eating dirt." But as Gilbert outgrew eating dirt, he found a new passion – birding. Gilbert felt this was his portal into ecology as a kid, and in college, it was a way to channel his interests. After receiving his bachelor's and master's degrees in biology, he became interested in wildlife and community science, which is how he heard about Snapshot Wisconsin. He would pursue his Ph.D. in Wildlife Ecology at UW-Madison, and while a Ph.D. student, he would start researching and writing about wildlife behavior.

What Are Animals Doing In The Cold?

One day, during a cold winter spell, Gilbert was holed up in his apartment trying to escape the -20 degrees outside. He wondered, "What are animals doing in this cold?" This led him to use Snapshot Wisconsin trail camera data to look at deer activity and habitat use during extreme cold and warm winter events.

DNR Quantitative Research Scientist and one of Snapshot's founders, Jen Stenglein, was there to help prepare the data for Gilbert. They used statewide data over two winters and looked at cameras with accurate dates, times and operational cameras. Gilbert and Stenglein mentioned that date, time, and location were essential to this paper.

"Knowing when and where pictures of deer were taken was critical to this and all other Snapshot Wisconsin data analyses. Volunteer trail camera hosts provide us with the important dates, times and locations linked to the photos. Placing an occurrence of deer in time and space allowed us to ask questions about the differences in deer habitat use during different times of the day, depending on the winter weather context," said Stenglein.

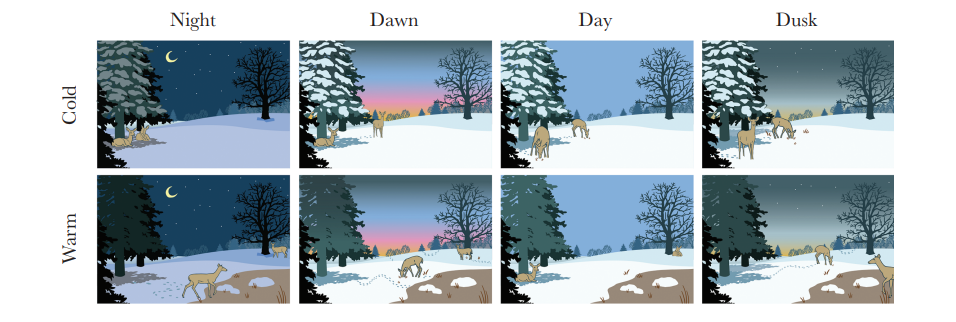

Gilbert hypothesized and found that deer were more active during the day during colder extremes (top row, Figure 1) compared to warmer winter days, where deer were more active at night. He also found that deer sought the protection of coniferous (pine) landscapes during colder extremes, while in warmer extremes they sought deciduous landscapes.

What makes this paper so unique? Gilbert and Stenglein mentioned that using trail camera data allowed a continuous look into the lives of deer and provided information on animal activity, which otherwise would be hard to gather. They could study deer behavior without studying deer behavior – meaning they weren't in the field using binoculars or drones to observe deer.

As for the future, Gilbert stated that climate change projections show winters may have a greater "whiplash" effect – extremely cold weather events followed by extremely warm events in winter, or vice versa. "We're seeing warming winter trends but also increasing frequency of these extreme weather events, leading to greater variation in wintertime temperatures," Gilbert said. While we don't know precisely what climatic changes we will see in Wisconsin, it is promising that Snapshot Wisconsin can provide the long-term and consistent data needed to continue tracking behavioral changes in space and time for deer and other wildlife.

Wildlife Friends And Foes

Earlier this year, Snapshot Wisconsin was featured in The New York Times! The article "Snarl, You're on Candid Camera" was written by Emily Anthes and published on January 16th, 2023. Featured in the article was Gilbert's most recent paper, Human disturbance compresses the spatiotemporal niche. This paper was published in the scientific journal PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America) and delved deeper into how these interactions between species can change with varying levels of human disturbance.

Volunteers often share photos featuring multi-species interactions, such as cranes and ducks sharing a lake or deer and turkeys foraging alongside one another. Inspired by those images, Gilbert focused on examining the time between pictures of different species to determine how likely the species were to interact.

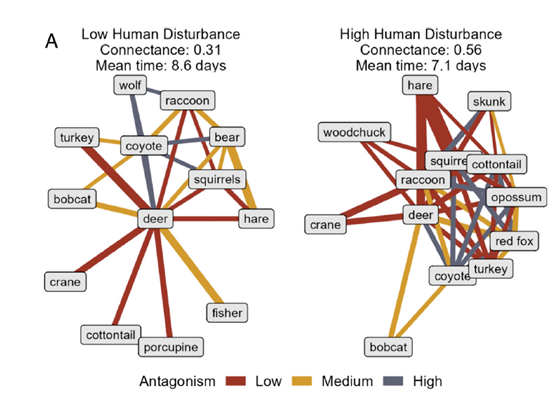

The species pairs were classified into high, medium, and low antagonism categories based on the species' evolutionary relationships and the species' relative body size and diet. For example, turkey and deer pairs were in the low antagonism category, while squirrel and coyote were considered highly antagonistic pair. Gilbert examined how the time between species detections within each pair varied based on their antagonism category. He found that high antagonism pairs had more time between photos than low antagonism pairs – 1.4 days more. In other words, highly antagonistic species pairs avoid one another more than low antagonistic pairs.

When investigating the impact of human disturbance on these interactions, he found less time between photos of species pairs in urbanized areas compared to rural areas—an average of two days less. The two-day difference was consistent regardless of whether the species pair was in the high, medium, or low antagonism category.

Figure 2 paints a picture of a social network for wildlife, demonstrating how the wildlife community has more and stronger connections across all antagonism levels in an area with high levels of human disturbance. These findings indicate that human disturbance could elevate stressful wildlife encounters by compressing the time shared by wildlife communities. It is difficult to get data like this on the links and networks between species, and trail cameras are a novel way to obtain this information.

Shout Out To Snapshot

It's incredible the leaps and bounds Snapshot Wisconsin has gone through since going live in 2018. Without our volunteers and partners, Snapshot wouldn't have millions of classified photos and data used in over 19 different publications. Neil Gilbert is one of the many reasons why Snapshot Wisconsin is where it is today, studying wildlife behavior using Snapshot Wisconsin trail cameras. But Gilbert wants to recognize all the Snapshot Wisconsin volunteers.

He is constantly amazed by the dataset; it is unprecedented for a state-level monitoring program. Considering how quickly image classification occurs, Gilbert has been asked if Snapshot is using a machine-learning algorithm, and he replies, "It's people-powered research!"

Gilbert is looking forward to the future of wildlife research with Snapshot Wisconsin and said volunteers are an essential key. "I'm excited about Snapshot's future as more and more years of data accumulate. We can move beyond single-year, relatively static analyses to longer-term work to understand how wildlife distributions and behaviors may change over time. The dedication of the volunteers is amazing to see and is crucial - it would be impossible for individual researchers to take care of and process the data for so many cameras!"

The Snapshot database has powered research, inspired interest in wildlife and widened understanding of how nature interacts with its environment. Who will be next to discover something new using Snapshot data?

Please see the citations below to read the full publications covered in this article.

Gilbert, N. A., Stenglein, J. L., Pauli, J. N., & Zuckerberg, B. (2022). Human disturbance compresses the spatiotemporal niche. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(52). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2206339119

Gilbert, N. A., Stenglein, J. L., Van Deelen, T. R., Townsend, P. A., & Zuckerberg, B. (2022). Behavioral flexibility facilitates spatial and temporal refugia during variable winter weather. Behavioral Ecology, 33(2), 446–454. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arab154

INTRODUCING: SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS PAGE

Just like Neil Gilbert used Snapshot data for his wildlife behavior research, so have other researchers used this massive dataset to learn more about the natural world around us. The program has been running long enough that there is a substantial list of publications using Snapshot data, covering a variety of topics from predator-prey interactions to improving automatic classifications. The Snapshot team would like to share this list with volunteers and so created the Scientific Publications webpage! Explore the many different ways Snapshot data has contributed to research, organized by topic. The page will be updated periodically, as publications are released, so make sure to check back often!

Snapshot Wisconsin's Call For Bear Den Reports

In 2021, the wildlife research team within the DNR's Office of Applied Science (OAS) launched a project to investigate black bear reproduction and diet. The project aims to estimate key reproductive values within each bear management zone that will be used to support bear management decisions. The project focuses on recording black bear reproduction parameters like average litter size, cub survival and litter frequency. Additionally, research staff will investigate if human food source availability could alter reproductive outputs in certain areas.

To gather this information, researchers survey bear dens each winter while bears are in shallow torpor, a light sleep state where the bears do not need to eat, drink, or even go to the bathroom. But how do they find these bear den locations? With the help of the public, of course! This project relies heavily on members of the people who are familiar with these wild areas, whether on their private land or public property across the state. "The public helps us a ton because it gives us locations that we can check and increases our ability to meet the sample size we need," DNR Large Carnivore and Elk Research Scientist and project lead, Dr. Jennifer Price Tack said in this short video [exit DNR] on the project.

Hoping to find unique ways to reach more Wisconsin residents about bear den reporting, research staff looked towards Snapshot Wisconsin. With nearly 2,000 active volunteers checking trail cameras nationwide, Snapshot Wisconsin was the perfect platform to reach such a large audience. In October 2022, a notice was sent to all Snapshot Wisconsin volunteers to safely report any bear dens they may have encountered while checking their trail cameras.

Volunteer Voices

It took no time at all for a Snapshot Wisconsin volunteer to report a black bear den in Marinette County! Kevin Schiebenes, a Snapshot Wisconsin volunteer since 2018, had initially been aware of the bear den near their family cabin after their dog had spotted it earlier in the year. "I was happy to see the DNR was doing this research so that we could report it to them," Schiebenes said.

An environmental science teacher, Kevin knew the den was occupied by noticing big claw marks on a nearby stump and seeing a prominent black figure in the ground when quietly approaching the area. After reporting the den using accurate GPS coordinates and location notes, Kevin was contacted by Dr. Jennifer Price Tack and her team to set up an initial meeting to confirm the den was active and if it was feasible to survey this den location. Upon arrival, they could quickly verify that the den was active by hearing the squeaks coming from the black bear cubs. During the winter, a second meeting was scheduled to evaluate if the cubs were big enough to spend a short time away from their mother during the survey.

Data Collection

Finally, the day arrived for the DNR research staff to conduct the bear den survey near the Schiebenes cabin and thankfully, they had plenty of helping hands. Joining Kevin was his wife Carrie and their two daughters Keira and Kylie, who were given an approved field trip from school to be a part of this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. The family was involved throughout the survey and enjoyed hearing about the planning process, seeing the equipment used, and participating in the "scientist huddle" for an after-survey debrief.

During the survey, DNR research staff each have a unique role in collecting biological data safely and efficiently from the bear dens. For the safety of people and the bears, staff specifically trained in field sedation will sedate the mother bear (sow) in the den using a long pole with syringe.

The cubs, however, are too young for sedation and are typically tucked into staff members' coats to maintain their body temperature throughout the survey. On this day, they had four family members ready to step up for this essential job. "When they [research staff] went to get the cubs out of the den and found there were four of them," Carrie said, "it was very special and exciting that there were four of them and four of us."

The sow's weight, body measurements, and age are collected during the survey. DNR research staff also place a GPS collar on the mother bear. The collars play a vital role in the data collection process for this project by allowing the team to locate the sow in the following years. They can determine reproductive success by revisiting the sow, such as cub litter size, litter frequency, and cub survival rate. Additionally, the collars will track the bears' movements across the landscape and how they use the area, which will help researchers understand foraging behavior.

For the cubs, DNR staff record their weight and sex and take a hair sample for genetics if time permits. After all necessary information is gathered from the sow and her cubs, they are reunited inside their den as quickly as possible.

Keira and Kylie could share their classroom experience by giving presentations and sharing photos of their unique opportunity. They recall the cubs being soft and fuzzy but not allowing their mom, Carrie, to wash their jackets from that day because of the tiny scratch marks left behind by the bear cubs.

With the bear den survey completed near the family's cabin, Schiebene's involvement with the nearby black bears is not over. Conveniently placed nearby, their Snapshot Wisconsin trail camera could capture photos of the same mother bear and her cubs in the upcoming months. "Checking the camera is always a fun part of the trips up north," Carrie said. Kevin added, "We are looking forward to spring and summer to see if we can see the cubs on the camera."

Science Community

Along with information gathered from the black bear litter and diet surveys, Snapshot Wisconsin data can further support black bear detections across the state. The statewide network of trail cameras monitored year around by volunteers like Kevin Schiebenes can help us understand the bear distribution and activity patterns throughout the day and year. Using various data collection tools, DNR research scientists and biologists can learn the many aspects of Wisconsin black bears and make informed wildlife management decisions.

The collaboration of DNR research scientists and Snapshot Wisconsin volunteers assisting with bear den reporting is just the start of what is possible for these community scientists. The wildlife research team will be looking for bear den reports again in Fall 2023, as bears will be starting to den up for the winter at that time.

The Snapshot Wisconsin team and fellow research staff appreciate the help of Snapshot Wisconsin volunteers and encourage them to watch for future black bear den reporting information and other community science opportunities available across the state!

For more information on the Black Bear Litter and Diet Survey and other DNR wildlife research, visit the Office of Applied Science's Wildlife Research page.

Learn more about community science opportunities with the Wisconsin DNR and our partners: Citizen-Based Monitoring.

A NOTE FROM THE TEAM:

Trained professionals conduct den surveys, and landowners and den reporters handle cubs under the supervision of DNR staff. Do not approach a suspected bear den if you find one. Keep an approximate 30-yard distance from a hole; if you want to report it because it looks occupied, take a GPS location and photo, and then quietly leave the area. With the warmer temperatures, bears are leaving their dens in search of food. Please remember to give bears plenty of space as they catch up on their calories! See the DNR's Living With Black Bears pamphlet for more information on what to do if you encounter a black bear or how to avoid bear conflicts.