Celebrating the 50th Anniversary of the Clean Water Act

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources proudly celebrates the 50th anniversary of the federal Clean Water Act, a foundational act to protect our shared waters nationwide, signed into law on Oct. 18, 1972.

Wisconsin has long been a national leader in addressing pollution in our treasured water resources and was one of the first states in the nation to apply for and receive delegation to implement the Clean Water Act's National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) program.

History of the Clean Water Act

Oct. 18 will mark the 50th anniversary of the Clean Water Act in the United States. In 1972, growing public awareness of the importance of water quality led to sweeping amendments, passed unanimously by both houses of Congress, to the Federal Water Pollution Control Act (originally enacted in 1948). The amended law became known as the Clean Water Act

and established a goal of making waters fishable and swimmable.

The Clean Water Act leveled the playing field among the states by setting a minimum level of national regulation that required permits with limits on how much pollution could be discharged into rivers and lakes. Most importantly, the Clean Water Act provided municipalities and states with federal funding to upgrade wastewater treatment plants. Over the years, the law has been improved to address additional issues of concern, such as industrial pretreatment, nonpoint pollution, toxics and biosolids.

Wisconsin has been a leader since the start. In the year that followed the passage of the Clean Water Act, Wisconsin created the Wisconsin Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (WPDES) program. This program enabled the state to implement the Clean Water Act on behalf of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in Wisconsin. EPA approved Wisconsin's WPDES program in 1974, making it one of the first programs authorized in the nation.

Wisconsin has continued to be a leader in water resource protection. The state was the first in the nation to require secondary treatment at wastewater treatment plants and among the first to develop statewide phosphorus criteria and thermal standards. Most recently, Wisconsin has set statewide PFAS surface water criteria for PFOS and PFOA. Wisconsin has also developed innovative strategies such as water quality trading and adaptive management to effectively address nutrient pollution from both point and nonpoint sources.

Making a Splash

Prior to passage of the Clean Water Act, open dumping of industrial wastewater and raw sewage was a common occurrence across Wisconsin. Thick industrial sludges covered stretches of rivers such as the Wisconsin and the Peshtigo from shore to shore. Many stretches of river were stained black and devoid of life. Our state has come a long way over the past 50 years and our water resources are now the featured jewels within our communities. People travel from all over the world to enjoy Wisconsin’s lakes, rivers and streams.

WISCONSIN RIVER TRANSFORMATION

The current state of the Wisconsin River is one of our state’s great success stories.

Home to many communities, dams, paper mills and other industries, the Wisconsin River was once known as the nation’s hardest working river. This hard work

eventually took a toll on the health of the river, and by the early twentieth century it was clear that the river was polluted. Newspapers from the 1920’s and 1930’s described it as almost an open sewer

and rotten with pollution.

Foam floated down the river and paper mill wastewater had so much fibrous material in it that the river had a bark-like matting upstream of some of the dams (see before/after Hat Rapids Dam images below).

Pollution-reduction measures began in the 1920’s but were not nearly effective enough to address the scope of the issues. While some mills had begun implementing early treatment technologies in advance of the Clean Water Act, the law’s 1972 passage required industries and municipalities to take action to meet effluent limits and secondary treatment standards. Additional requirements for industries and wastewater treatment facilities would be developed over time to continuously improve the quality of the water and its aquatic and surrounding habitats.

While some parts of the Wisconsin River are still listed as impaired, it is worth celebrating how much the water has improved over the past 50 years.

In 1976, the average amount of biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) (a measure of the impact of a waste on the oxygen content in a receiving water body) discharged to the upper Wisconsin River was approximately 286,000 pounds per day. Simply put, BOD is a common indicator of the amount of organic pollution in water.

Over the course of several years in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, a concerted effort of water quality monitoring and analysis culminated with new rules that became Wisconsin’s first total maximum daily load (TMDL). The Wisconsin River BOD TMDL project successfully removed dissolved oxygen impairments and eliminated the recurrence of floating mats and fish kills. By 2021 this has been reduced to 13,000 pounds per day, a 95% decrease.

While this early effort was a tremendous success in water quality improvement, problems remain. Nutrient (phosphorus and nitrogen) pollution remains a major concern in Wisconsin and across much of the US.

In 2010, Wisconsin became one of only a few states with statewide phosphorus standards – these standards are implemented through the Clean Water Act in WPDES permits. With the permit process in place, phosphorus reductions in Wisconsin’s waters have been incredible: phosphorus loading from point sources, a common cause of algal blooms, has decreased from 3.96 million pounds per year statewide in 1995 to less than one million pounds per year in recent years and continues to trend downward.

As a result of these efforts, the Wisconsin River is once again a popular place for recreating and fishing, and the work to further improve the water quality continues.

Floating organic matter at the Hat Rapids Dam in 1969.

Hat Rapids Dam in June 2022.

Looking Ahead

While we celebrate what has been accomplished over the last 50 years, our work is not complete. Some Wisconsin waterbodies are still impaired and not meeting their designated uses.

The 2022 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) offers a great opportunity, likely not seen since the Clean Water Act 50 years ago, to make exponential progress in addressing impacts to our water resources. The BIL will provide Wisconsin communities nearly $800 million over the next five years to upgrade infrastructure and address water quality impacts. We look forward to working with our communities and our industry partners in continuing to protect and restore Wisconsin's world-class water resources.

Monitoring

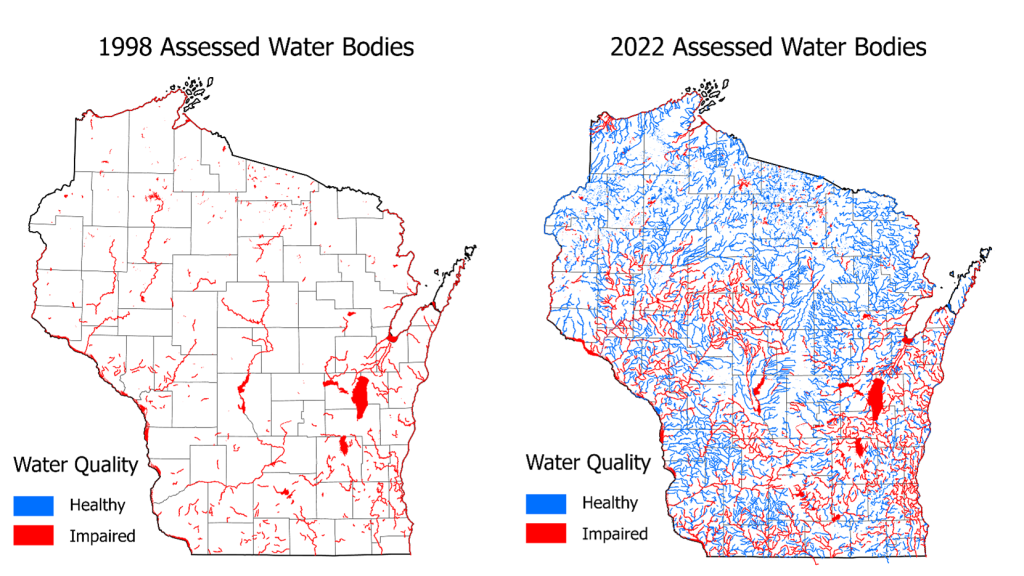

The maps above show water quality conditions across the state of Wisconsin based on Clean Water Act (CWA) section 303(d) and 305(b) requirements for the 1998 and 2022 reporting cycles. Waters with an identified impairment are depicted in red, and waters with at least one indicator of good water quality are displayed in blue.

In the past quarter century, the amount of surface water across the state evaluated as required by CWA 303(d) and 305(b) increased nearly four-fold. Earlier years of water quality reporting solely focused on identifying impairments. Still, improved technology has allowed more recent efforts to include identifying rivers, lakes and streams that are meeting water quality goals. Having a clearer and more comprehensive picture of water quality across the state has provided for better resource restoration and protection planning and enhanced capability to answer Wisconsin citizens who ask, "How is my waterway doing?

Clean Water State Revolving Fund

The Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) was created by the 1987 amendments to the Clean Water Act (CWA) as a financial assistance program for a wide range of water infrastructure projects under 33 U.S. Code §1383. The program is a powerful partnership between EPA and the states that replaced EPA's Construction Grants program. States have the flexibility to fund a range of projects that address their highest-priority water quality needs. The program was amended in 2014 by the Water Resources Reform and Development Act.

Using a combination of federal and state funds, state CWSRF programs provide loans to eligible recipients to:

- construct municipal wastewater facilities,

- control nonpoint sources of pollution,

- build decentralized wastewater treatment systems,

- create green infrastructure projects,

- protect estuaries, and

- fund other water quality projects.

Since 1991, the Clean Water Fund Program (CWFP) in Wisconsin has provided affordable financial assistance to municipalities for publicly owned wastewater and water quality-related stormwater infrastructure projects needed to achieve or maintain compliance with federal and state regulations (such as WPDES permits). Wisconsin has provided more than $6.2 billion in financial assistance to municipalities through two Environmental Improvement Fund (EIF) programs for water infrastructure projects that protect and improve public health and water quality for current and future generations.

Wetlands

Since the 1970s, wetland protection and restoration efforts have expanded in Wisconsin thanks to the legacy of the Clean Water Act. To preserve healthy wetland ecosystem services, developments proposed in wetlands today must avoid and minimize impacts before being permitted. Most permitted impacts are offset through restored wetland sites at private wetland compensatory mitigation banks and the DNR's Wisconsin Wetland Conservation Trust. Through this regulatory process, wetland restorations have averaged 3 acres for every acre of wetland impacts. Wetland conservation and wetland restoration efforts have preserved many of the wetland functions that wetlands provide to the people and wildlife of Wisconsin.

The water protections and awareness set in motion by the Clean Water Act have created opportunities for Wisconsinites to enjoy their millions of acres of wetlands. Whether for fish spawning and bird nesting habitat, water quality and sediment removal, or flood control and water recharge to streams, wetlands provide significant ecological and community benefits.

CAFO

As part of implementing the Clean Water Act, Wisconsin ensures water quality protection by requiring that CAFOs have a DNR-approved WPDES permit in place to operate. CAFO WPDES permits ensure farms use proper planning, nutrient management and structure/system construction to protect Wisconsin waters. These permits apply only to water quality protection.

Storm Water

Urban stormwater runoff contains pollutants from roads, parking lots, construction sites, industrial storage yards and lawns. The DNR's Storm Water Program regulates stormwater discharges from construction sites, industrial facilities and municipalities.

Congress amended the federal Clean Water Act in 1987 to control stormwater pollution. In 1990, federal regulations required owners of stormwater pollution sources (including many industries, municipalities and construction sites) to have National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) Stormwater Permits. The permits require permit holders to create plans and install management practices that eliminate or reduce stormwater pollution.

To meet the requirements of the federal Clean Water Act, DNR developed the Wisconsin Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (WPDES) Storm Water Discharge Permit Program. The WPDES Storm Water Program regulates the discharge of stormwater in Wisconsin from three potential sources:

Regulated stormwater discharges are considered point sources, so owners or operators of these sources are required to receive a WPDES permit for their discharge. This permitting mechanism is designed to prevent stormwater runoff from washing harmful pollutants into local surface waters such as streams, rivers, lakes or coastal waters.