Jumping worms

Amynthas spp.

Mature jumping worm. Photo Credit: Susan Day, UW-Madison Arboretum

Mature jumping worm. Photo Credit: Susan Day, UW-Madison ArboretumJumping worms are non-native, invasive earthworms first confirmed in Wisconsin in 2013. Native to eastern Asia, they present challenges to homeowners, gardeners and forest managers. Their name comes from their behavior: When disturbed, they thrash, spring into the air and even shed their tails to escape.

This webpage will help you learn about jumping worms and their effect on yards, gardens and forests, how to prevent their spread and what to do if they're already on your property.

Introduction

Endemic to parts of Asia, jumping worms first arrived in North America sometime in the late 19th century, most likely in imported plants and other horticultural and agricultural materials. Since then, jumping worms have become widespread across much of the midwestern, southeast and northeast United States. Most recently, they have appeared along the west coast and some parts of southeastern Canada.

In 2013, jumping worms were confirmed for the first time in the upper Midwest at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Arboretum.

Jumping worms aren't the first non-native, invasive earthworms in Wisconsin. All earthworms in Wisconsin are non-native, and many are considered invasive.

No native earthworms have existed in Wisconsin since the last glacier moved through the state thousands of years ago, scouring the landscape down to the bedrock. The familiar earthworms we see in our gardens and put on our fishing hooks originated in Europe and were brought here by settlers.

Although all earthworms can harm landscapes and forests, jumping worms may pose a bigger threat than European worms.

Why Jumping Worms Are A problem

Jumping worms with granular soil. Photo Credit: Susan Day, UW-Madison Arboretum

Jumping worms can quickly transform soil into dry, granular pellets with a texture similar to discarded coffee grounds. This altered soil structure is often unaccommodating to ornamental and garden plants and inhospitable to many native plant species. In addition, they can deplete the soil of nutrients and impact soil organisms. In many cases, invasive plants thrive where jumping worms live.

Identification And Biology

Where To Look For Jumping Worms

- Jumping worms do not burrow far into the soil. They live on the soil surface in debris and leaf litter or within an inch or two of the topsoil.

- Look for them in your yard, garden, forest, mulch pile, compost, potted plants and other suitable places.

buy bare root plants if available.

Photo Credit: UW-Madison Arboretum

compost.

Photo Credit: UW-Madison Arboretum

How To Identify Jumping Worms

- Smooth, glossy, dark gray/brown color.

- The clitellum*, the lighter-colored band, is cloudy-white to gray and completely encircles the body; its surface is flush with the rest of the body.

- Snake-like or "flip-flopping" behavior when disturbed.

- They tend to occur in large numbers; where there's one, there are always more.

*The clitellum is a band of glandular tissue that partially or fully encircles the worm's body. This is where cocoons are produced.

Comparison: Jumping Worm Vs. European Nightcrawler

Jumping Worm European Nightcrawler

Brown/gray. Pink/reddish. Bodies are sleek, smooth and firm. Bodies are thick, slimy and floppy. Thrash when disturbed; snake-like movement. Wiggle and stretch when disturbed. The light-colored, smooth clitellum is flush with the body, relatively close to the head, and completely encircles the body. Reddish or pink clitellum* slightly raised from the rest of the body. Partially encircles the body, like a saddle. Creates uniform "coffee grounds" casting layer. Creates dispersed piles of casts (excrement). May drop tail segments when handled roughly. Will not drop tail segments. When To Look For Jumping Worms

Unlike all other species of earthworms in Wisconsin, jumping worms have an annual life cycle. As such, they are most noticeable in late summer/early autumn, when most are fully mature.

Time Of Year Activity April – May Tiny jumping worms hatch from cocoon-encased embryos. Summer months Worms feed and grow. August – September Mature worms reproduce by depositing cocoons in their surroundings. Jumping worms are parthenogenic; each worm can reproduce independently without a mate. First freeze Adult worms die. Winter months Jumping worm embryos spend cold months protected in cocoons (about the size of a mustard seed). It takes about 90-120 days between hatching and reproduction. Unlike European earthworms, jumping worms in Wisconsin can complete two generations per year.

Cocoons are light to dark brown

and only 2-3mm in diameter,

making them very difficult to see in the soil.

Photo Credit: Marie Johnston,

UW-Madison ArboretumNewly hatched jumping worm.

Photo Credit: Marie Johnston,

UW-Madison Arboretum

Effects

What Jumping Worms Do To The Soil

Jumping worms feed on organic matter, such as leaf litter and mulch, and within the soil. They excrete grainy-looking, hard little pellets ("castings") that alter the texture and composition of the soil.

In addition to consuming nutrients that plants, animals, fungi and bacteria need to survive, the resulting soil, which resembles large coffee grounds, provides poor structure and water retention for many forest understory plants and garden plants. Planting seedlings or transplanting mature plants into this granular topsoil can be especially difficult.

Jumping worm-infested soil in a potted plant. Photo Credit: Eric Hamilton, UW-Madison

The characteristic coffee-ground-like soilbleft behind by jumping worms.bPhoto Credit: Eric Hamilton, UW-Madison

Jumping Worm Effects On Forests

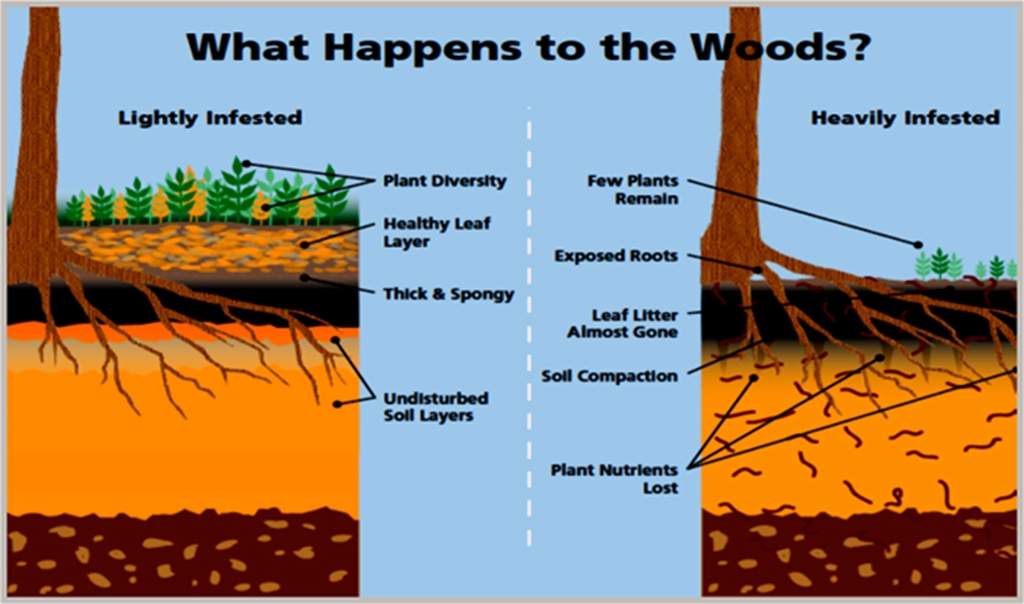

All non-native earthworms, not just jumping worms, can harm forests by changing the soil structure and forest floor vegetation. Their feeding and burrowing behaviors can result in a loss of soil moisture, compacted soil, exposed roots, erosion and an increase of pathogens and non-native plants. The result is reduced diversity of native plants and animals in delicate forest ecosystems.

Damage is done to forests by jumping worms and other earthworms.

Management And Prevention

There is no "magic bullet" to control jumping worms, at least not yet. Management mainly involves taking precautions to not move them onto or off your property. However, if they are already there, there are strategies you can use to reduce and slow the spread.

Prevention

Prevention is by far the best approach to jumping worms. Even if jumping worms are on part of your property, take care not to introduce them to uninfested areas.

The following simple steps will reduce the spread of jumping worms:

- Educate yourself and others to recognize jumping worms.

- Watch for jumping worms and signs of their presence.

- Arrive clean, leave clean. Clean soil and debris from vehicles, equipment and personal gear before moving to and from a work or recreational area — they might contain jumping worms or their cocoons.

- Use, sell, plant, purchase or trade only landscape and gardening materials and plants that appear free of jumping worms.

- Sell, purchase or trade only compost and mulch that was heated to appropriate temperatures and duration, following protocols that reduce pathogens.

Plant sales can still be safely conducted, although extra care and attention must be taken to ensure jumping worms are not accidentally moved into the soil. Proper treatment of compost and mulch before purchase kills jumping worms and other pests and diseases. Photo Credit: University of Wisconsin-Platteville Plant Sales

Many garden clubs and other non-profit organizations hold plant sales to raise money and assist the public in procuring plants for their gardens and landscapes. Plant sales are important social events that build community and foster a love of gardening and nature.

Unfortunately, plant sales can be a way for jumping worms and their cocoons to spread. However, practices can be implemented to minimize significantly the introduction and spread of jumping worms through plant sales:

- Make sure that plants being sold are purchased from reputable nurseries that have taken steps to minimize the potential infestation of jumping worms in their products.

- If plants are being dug from private properties, ensure that those locations are free of jumping worms. If not, the plants should be bare-rooted and repotted into clean soil before being brought to the sale.

- Potted plants should be kept off the ground or on landscape fabric to minimize the chance of jumping worms crawling into the pots.

- Before the sale, plants should be inspected. Look for topsoil granularity, which is a telltale sign of jumping worm activity. If identified, discard the plant.

- During the sale, make outreach material about jumping worms available.

What to do if jumping worms are already on your property

- Don't panic. You can continue enjoying your yard, trees and garden by taking precautions. Just because you have jumping worms in one part of your property doesn't mean that they are everywhere. Take precautions to avoid spreading them.

- Remove and destroy jumping worms when you see them. Seal them in a bag and throw them in the trash – the worms will not survive long. Reducing the adult population will eventually reduce the number of egg-carrying cocoons in the landscape.

- Heat treatment. Jumping worms and their cocoons are sensitive to high temperatures. Research has shown that neither worms nor cocoons can survive 104°F or higher for over three days. Under the appropriate conditions and management, compost piles can easily reach this temperature. In addition, using clear plastic to cover the topsoil of gardens and lawns exposed to full sun can raise the temperature enough to kill cocoons, even in the spring.

- Chemical treatment. Research has shown that the biological insecticide BotaniGard can significantly reduce the abundance of jumping worms. Do not use the product near any pollinator animals.

- Experiment. If necessary, try a variety of plants or consider alternative landscaping in heavily infested parts of your property. Try a variety of mulch products such as straw or native grass clippings such as big bluestem, Indian grass, etc.

- Keep your chin up. Research is moving forward to find ways to control and manage jumping worms. As you experiment with controls and adapt your gardening practices, share your successes (and failures) with fellow gardeners, land managers and researchers so that we can all learn from each other!

Resources

Articles

CANCEL EARTHWORMS by Julia Rosen, The Atlantic, January 2020.

What's With These Invasive "Crazy" Worms and Why Can't We Get Rid Of Them? by Katherine Harmon Courage, Vox, June 2021.

Jumping worms: The creepy, damaging invasive you don't know by Matthew L. Miller, a science communicator for The Nature Conservancy. October 2016. This short article is an excellent introduction to earthworms in general and the jumping worm in particular.

Asian jumping worms: What we know, with UW-Madison's Brad Herrick from AWaytoGarden.com. March 2018. Questions and answers with UW-Madison Arboretum's ecologist Brad Herrick.

Fact sheets

Jumping worms: Printable document from the Wisconsin DNR.

Jumping worms homeowner guide by Jumping Worm Outreach, Research and Management Working Group (JWORM).

Jumping worms informational postcard by UW-Madison Arboretum. 2022.

Videos

Invasive jumping worms: Longer video encompasses most of what we know about jumping worms. University Place Garden and Landscape Expo, Brad Herrick, UW Arboretum. Produced in February 2020.

Jumping worms in Wisconsin: This 40-second video from the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel highlights jumping worms' distinctive thrashing movement. Produced in December 2016.

Invasion of the earthworms: A two-minute National Science Foundation video that discusses the problems non-native earthworms cause in forests. It was produced in September 2011.

Ralph Nuzum lecture series: Impacts of invasive earthworms on forests. A 53-minute talk by Evan Larson, professor of geography at UW-Platteville, discusses the effect of non-native earthworms on ecosystems of northeastern forests. She produced in August 2015.

The Wisconsin jumping worm webpage is a collaborative effort between the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, the University of Wisconsin-Madison Arboretum and the University of Wisconsin-Madison Extension.