Snapshot Newsletter October 2025

As Wisconsin’s forests erupt in a riot of autumnal colors and pumpkins reach their full rotundity, we welcome that chill seeping into the air. The days are getting shorter – which means, of course, the nights are growing longer. With Snapshot Wisconsin’s roughly 2,000 trail cameras, there are more chances to capture wildlife’s dark side.

In this edition of the Snapshot Wisconsin newsletter, we’re celebrating both the lengthening night and the critters that are out and about – and in front of our cameras – after sunset.

Would you like to receive Snapshot Wisconsin information and news sooner? Subscribe via GovDelivery and be the first to read the latest happenings with Snapshot Wisconsin and Wisconsin wildlife research.

Snapshot Wisconsin Trail Camera Project – Sign up for emails about new Snapshot Wisconsin newsletters.

Snapshot Wisconsin Educator's Bulletin – Sign up for emails about using Snapshot in classroom and outreach.

Illuminating The Science of Eyeshine

Have you ever taken a picture of your dog or cat with the flash on, only to look at the photo and realize that the cuteness is overshadowed by your pet’s glowing eyes? This sometimes-creepy effect is known as “eyeshine” and it can also be observed in many Snapshot Wisconsin wild animal photos, especially at night.

Why Are So Many Animals Nocturnal — And How Do Our Trail Cameras Capture Them?

Somewhere in Adams County, four young coyotes pause, ears pricked, as something in the darkness attracts their attention. Snapshot Wisconsin has captured many after-dark moments like this, when dozens of species are at their most active. We look at why the nightlife is so popular, and how our trail cameras manage to snap these stunning images.

Creatures Of The Wisconsin Night! What Images They Make!

In the spirit of this spooky season, Snapshot staff combed through our archives to share our favorite freaky, creepy or just plain weird trail cam images. Enjoy!

A recent paper published in the scientific journal Wildlife Research explored the potential for monitoring an important aspect of a population using only trail camera images – and Snapshot Wisconsin data played a central role.

Illuminating The Science Of Eyeshine

Have you ever taken a picture of your dog or cat with the flash on, only to look at the photo and realize that the cuteness is overshadowed by your pet’s glowing eyes? This sometimes-creepy effect is known as “eyeshine” and it can also be observed in many Snapshot Wisconsin wild animal photos, especially at night.

Animals that exhibit eyeshine do not actually have glowing eyes. Instead, eyeshine is caused by an anatomical adaptation in the eyes of animals that are active at twilight (crepuscular) or night (nocturnal). The tapetum lucidum is a special membrane behind the retina that acts like a mirror to reflect light. In dim conditions, light photons are used twice: once as the light enters the eye and again as the light is reflected back out through the pupil. This is quite advantageous for animals that hunt in the dark, where light is a limited resource. Humans do not have a tapetum lucidum, which is why we rely on candles and lightbulbs to see at night.

There are many kinds of animals that have a tapetum lucidum, including cows, alligators and even sharks! In Snapshot Wisconsin photos, you are likely to see the eyeshine effect in nighttime photos of deer, coyotes, bobcats and more. When we see eyeshine in a photograph, we are observing extra light caused by the flash of the camera reflecting off the tapetum lucidum. This is true of all types of camera flashes, even the invisible infrared flash of the Snapshot Wisconsin camera traps (read how invisible infrared works in the next story!).

By the way, eyeshine is not the same as the “red-eye” effect seen in photos of human eyes, which is caused by your pupils not reacting to the flash quickly enough and letting too much light into the eye. The excess light exposes the choroid, a layer of vascular tissue which supplies blood to the retina – all that blood makes our eyes appear red.

While a flash photo is the only way to see the red-eye effect in humans, there’s no flash needed to spot eyeshine. It’s observable when any bright light is reflected back from the tapetum lucidum and you are positioned behind a single-point light source, such as a flashlight. Next time you are riding in a car at night, look on the side of the road to observe eyeshine in any animals you may pass. If walking outside at night, slowly move your flashlight around to see if you can catch the eye reflections of nighttime creatures just beyond your light beam. – Madeleine Soss

Why Are So Many Animals Nocturnal — And How Do Our Trail Cameras Capture Them?

Somewhere in Adams County, four young coyotes pause, ears pricked, as something in the darkness attracts their attention. In Waukesha County, a barred owl perches on a leafless tree branch in the depths of night. And in Sawyer County, a northern flying squirrel sails from one tree to the next, limbs outstretched, resembling a ghostly kite.

Snapshot Wisconsin has captured these and many other after-dark moments, when dozens of species are at their most active. But why do so many animals, especially mammals, live on the dark side – and how do our trail cameras manage to snap these stunning images?

Nocturnal animals have been around for more than 200 million years – including the first mammals, which were active at night to avoid becoming lunch for dinosaurs and other diurnal, or day-active, predators. It’s a pattern we still see today, with about 70% of mammals considered to be nocturnal.

These species have various traits that help them navigate the night, including sharp hearing or echolocation, an enhanced sense of smell and even highly sensitive whiskers that can detect the air stirred up by another critter moving nearby in the darkness.

Nocturnal, Diurnal, Crepuscular Or Cathemeral?

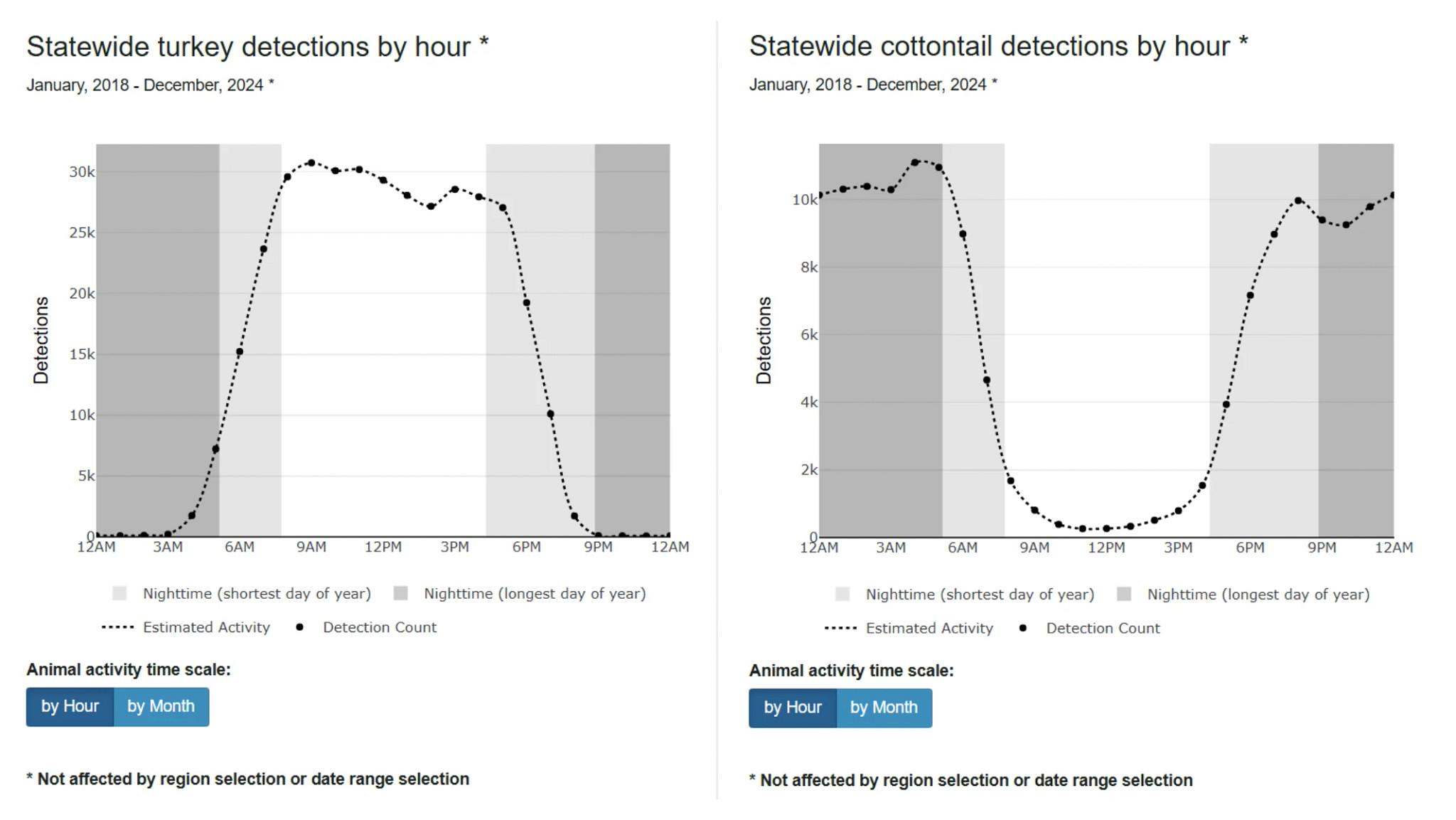

Thanks to Snapshot’s community scientists, who collect accurate dates and times for trail cameras they host, the Snapshot Wisconsin Data Dashboard charts activity patterns for 22 species regularly seen around the state. Check out the dashboard and you’ll notice that mammals from beavers to bobcats are most active either at night or during twilight, which means they’re crepuscular rather than purely nocturnal. In fact, the only three diurnal species that appear on our dashboard are birds: pheasants, sandhill cranes and turkeys.

Of course, not all birds are diurnal. One of the animals most closely associated with night is the owl. These winged hunters have exceptional night vision, with large eyes that, in some species, make up as much as 5% of their body weight. Those big eyes also have a relatively high number of rods, the photosensory cells that help an animal see in low light. (Fun fact: Only about two-thirds of the world’s roughly 250 owl species are nocturnal, but all have excellent low-light distance vision.)

A small number of animals aren’t nocturnal, diurnal or crepuscular, including one species that shows up frequently on Snapshot cameras. Coyotes are considered cathemeral, which means these opportunistic omnivores can be active day or night. This strategy allows individuals to adapt quickly to local conditions, including food availability.

Picture That

The adaptations of nocturnal animals are impressive, but so is our ability to glimpse them going about their lives in darkness. The capabilities of today’s trail cameras would have been unimaginable back in the 1880s, when Pennsylvania politician and nature enthusiast George Shiras III devised a way to photograph animals at night in their natural habitat.

Despite his innovative approaches, Shiras was limited by the technology of his day, including the use of explosive (and dangerous) flash powder for illumination. Today, many trail cameras, including those deployed in the Snapshot Wisconsin program, use what’s known as no-glow infrared to light up a nightscape without disturbing the wildlife.

There are also low-glow infrared and even LED and old-school incandescent flash trail cameras out there, but let’s focus on the no-glow variety.

First, you may have heard that trail cameras use passive infrared (PIR), but this has nothing to do with illumination. PIR is all about the camera being able to sense that there is something it should photograph. It does this by detecting minute changes in infrared radiation, which humans perceive as heat. As an animal moves across the landscape, the camera’s PIR sensor can pick up a change in heat, from the ambient or environmental temperature to the warmer body and back again, which triggers the camera to take a photograph. The PIR motion sensor is active whenever the camera is operational, day or night.

To Glow Or Not To Glow, That Is The Question

Infrared used for illumination, however, is operational only in low-light situations, primarily at night. A “no-glow” trail camera illuminates its subject by emitting wavelengths of light that are invisible to humans and most animals – wavelengths of 940 nanometers (nm) if you want to be precise. That’s well outside the visible light spectrum for humans of about 380-750 nm. (Some animals, including many snakes and fish species, are able to see infrared light.)

By contrast, “low-glow” trail cameras emit light at 850 nm but include some slightly shorter wavelengths, which humans and most animals will perceive as a faint red light.

While the infrared illumination is less disruptive to animals, there is a trade-off: Because the light is emitted in wavelengths outside the color spectrum, the images are in black and white. If you are flipping through a magazine or scrolling online and see color images of wildlife at night, they were either taken using visible illumination, such as LED lights or an incandescent flash, or colorized during the editing process.

While they may be “only” in black and white, Snapshot Wisconsin’s nighttime images capture a glorious spectrum of our diverse nocturnal wildlife, from highly specialized owls to opportunistic coyotes that are ready for action 24/7. – Gemma Tarlach

Creatures Of The Wisconsin Night! What Images They Make!

If you’ve spent any time in our curated Snapshot image collection, you’ve seen plenty of nighttime photos of nocturnal animals just going about their business, from a pack of wolves loping through the forest to an inquisitive raccoon inspecting a trail camera.

But every now and then, our network captures an image that seems anything but ordinary. Maybe it’s a fast-moving animal that appears as a spectral blur, or a glimpse of unusual behavior, such as a four-legged animal walking upright.

In the spirit of this spooky season, Snapshot staff combed through our archives to share our favorite freaky, creepy, or just plain weird trail cam images. Enjoy!

Have you seen The Shining? These two deer in Pierce County remind us of a certain set of twins who roamed the halls of the Overlook Hotel in Stanley Kubrick’s classic horror flick, based on the Stephen King novel. And there is a kind of shining happening here: Read more about animals’ eyeshine in this edition’s feature story, above.

An owl spreads its wings over what appears to be a small pond in Langlade County, the water reflecting its gaze with eerie clarity.

The spookiest sights are often things we don’t see. This bobcat in Iowa County might be leaping after off-camera prey, but it sure looks like the feline is grappling with an unseen entity.

Is this deer in Portage County just saying hello, or is it auditioning for a role in the next Blair Witch movie? We can’t say for certain, but we heard a rumor that it has an agent.

No, it’s not a skinwalker. It’s an owl taking flight in Sauk County. The bird’s wings are a barely visible blur of motion while its long legs look almost fang-like below its round face and large, glowing eyes.

We’d love to know the full story behind this moment captured in Monroe County. Is this bobcat preparing to pounce on the unsuspecting deer? Or are the animals locked in a staring contest, one so intense that the bobcat arches its back, which can be a sign it’s feeling defensive.

Social media is full of alleged ghost sightings, but we can assure you this isn’t one of them. At first glance, it looks like a hooded figure is standing at the top of a small slope. But look again: It’s the back half of a deer captured mid-bound, leaping away from a Snapshot camera in Outagamie County. The hooded figure’s “head” is actually the deer’s tail.

Fishers are agile tree-climbers but, when on the ground, they walk on all fours. Raccoons are also generally quadrupedal, unless they’re carrying something. So the postures of both this St. Croix County fisher and Florence County raccoon are unusual. Add the illusion of a blank stare, created by the animals’ eyeshine, and these images look like they’re straight out of a zombie movie.

Nearly hidden in the vegetation, this stealthy Winnebago County otter seems to be stalking the camera, tongue out as if licking its chops in anticipation of a late-night snack. Sorry, otter, but trail cameras taste terrible.

Snapshot Data Contributes To New Scientific Publication: Estimating Eastern Wild Turkey Productivity Using Trail Camera Images

A recent paper published in the scientific journal Wildlife Research explored the potential for monitoring an important aspect of a population using only trail camera images – and Snapshot Wisconsin data played a central role.

The study focused on the eastern wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo silvestris), which is native to Wisconsin and can be found across much of the eastern half of the United States. In particular, the team was interested in the Wisconsin turkey population’s productivity, which can be a factor in understanding the overall size and health of the species within our state.

Productivity in a species could be thought of as a measure of how successful a population is in raising the next generation, from reproducing to rearing young. Traditional productivity studies require on-the-ground surveys of nests and other fieldwork, which can be time-consuming and expensive, as well as limited to a handful of sites.

For this study, the first of its kind, the team relied on trail camera images alone. The scientists analyzed more than 38,000 turkey triggers, or three-photo bursts, captured by Snapshot trail cameras across Wisconsin over five summers, 2016-2020.

The team classified each trigger by the number of hens (breeding-age females) and poults (juveniles). That information was then used to calculate the percentage of hens that had successfully reproduced and reared their poults, as well as other metrics.

Combined with additional data collected by Snapshot cameras, such as specific geographic location and date of trigger, the team estimated that more than a third of hens (36%) were successful during the study period. Interestingly, forested landscapes seemed to provide an advantage for these turkey moms over grassland environments.

The study included an estimate of the number of poults added annually to Wisconsin’s wild turkey population by summer’s end. However, the coauthors noted the estimate was lower than those derived from traditional surveys, possibly because trail cameras may not always capture the smaller poults.

While additional research is needed to test and refine the approach, this first-of-its-kind attempt to measure productivity using only trail cameras could one day lead to more efficient ways of monitoring the populations of wild turkeys in Wisconsin and beyond.

DNR staff are indicated in bold.

Estimating eastern wild turkey productivity using trail camera images

Hannah E. Butkiewicz, Jennifer L. Stenglein, Jason D. Riddle, Shelby A. Truckenbrod and Christopher D. Pollentier

Key Findings:

- This is the first study to date that has attempted to estimate wild turkey productivity across a large geographic area using trail cameras alone.

- Productivity is a measure of a population’s success reproducing and rearing young.

- Traditional productivity surveys require visiting nests and other fieldwork, and are limited by time, geography and available resources. Estimating productivity using trail camera images alone could allow scientists to analyze a population over a much larger geographic area and over longer periods of time.

- The team analyzed 38,671 turkey triggers, or three-photo bursts, over five summers.

- The paper included three measures of wild turkey productivity, which were lower than those derived from traditional productivity survey methods, suggesting additional research is needed to refine the approach.