Snapshot Newsletter January 2026

Celebrating Winter And The Science Of Phenology

Wisconsin winters can be a wild ride! From snow dumps and blasts of Arctic air to mild, sunny stretches and even a rare tornado, our state sees a wider range of conditions than many others during the colder months.

In this edition of the Snapshot Wisconsin newsletter, we’re digging into the science of the season like a badger excavating a burrow. Learn about the Snapshot Phenology Project, an exciting new collaboration that’s funded by NASA, and the statewide network of partners and volunteers making it possible. The data collected will give us a better-than-ever understanding of seasonal changes and how flora and fauna respond, not just in winter but year-round.

We also take a look at how Wisconsin wildlife survives the cold and share some of our favorite winter images captured by Snapshot cameras.

Would you like to receive Snapshot Wisconsin information and news sooner? Subscribe via GovDelivery and be the first to read the latest happenings with Snapshot Wisconsin and Wisconsin wildlife research.

Snapshot Wisconsin Trail Camera Project – Sign up for emails about new Snapshot Wisconsin newsletters.

Snapshot Wisconsin Educator's Bulletin – Sign up for emails about using Snapshot in classroom and outreach.

The Snapshot Phenology Project: Snapshot Cameras To Measure Seasonal Change

Wisconsin has a temperate climate, characterized by striking seasonality, from spring's sudden "green-up" to winter's deep chill. This gives us a glimpse into the world of phenology: the study of the cyclical timing of natural events. Now, phenology is taking center stage in an exciting new phase of Snapshot Wisconsin research, thanks to a grant from the NASA Citizen Science for Earth Systems Program.

The Snapshot Phenology Project Kickoff

Get a behind-the-scenes look at how Snapshot volunteers, DNR staff, University of Wisconsin-Madison researchers and Wisconsin’s libraries and nature centers collaborated recently to assemble and deliver equipment for our new Phenology Project statewide. Hundreds of snow stakes and temperature sensors were distributed and installed. We also hear from project participants on why all the hard work and hustle are worth it.

Humans have come up with all kinds of hacks to stay warm in colder climates: fires, shelters, furnaces, jackets, gloves, blankets, toe warmers and more. Have you ever wondered how wildlife endures the frigid temps all winter without these things? Similar to us, wild animals have developed hacks, or adaptations, to beat the cold and survive. These adaptations can be changes in physical form, behavior or both.

Snapshot Cameras Capture Wild Winter Scenes

Hey, Snapshot Wisconsin volunteer camera hosts, thank you! We’re especially thankful for your dedication during the cold and snowy months, when many of you lace up your boots, strap on snowshoes and head out into the chilly air to check on your trail camera. Without you, we’d miss a lot of wonderful moments out in the wild. Check out some of our favorite winter captures that you made possible.

Hats Off To The Natural Resources Foundation Of Wisconsin

We pause to celebrate a big anniversary for one of Snapshot Wisconsin's partners.

The Snapshot Phenology Project: Snapshot Cameras to Measure Seasonal Change

Wisconsin has a temperate climate, characterized by striking seasonality. Throughout the year, the length of the day changes continuously, affecting ambient temperature and many aspects of the natural world. In the spring, warming days trigger the rapid emergence and growth of leaves, a phenomenon called “green-up.” As summer gives way to autumn and winter, many of our breeding songbirds depart for southern lands, deer enter the rutting season and black bears prepare to den up. These and many other cyclical changes in the plant and animal communities of Wisconsin are glimpses into the world of phenology, the study of the cyclical timing of natural events. Now, phenology is taking center stage in an exciting new phase of Snapshot Wisconsin research, thanks to a grant from the NASA Citizen Science for Earth Systems Program.

In addition to the motion-triggered photographs of wildlife that we all know and love, Snapshot Wisconsin cameras are also programmed to take a photo at a set time every day. These timelapse photos provide a sense of the day-to-day environmental conditions at each of our sites. In the context of phenology, these photos enable us to explore seasonal changes across the state by investigating the timing of green-up in spring, the length of the snow season and much more.

There’s always more to learn, of course. To expand our understanding of seasonal phenology, a subset of Snapshot Wisconsin volunteers has joined the Phenology Project. Read on to learn more about the new data being collected and how it will be used to answer research questions about the changing seasons.

Microclimate Data

To understand how the seasons affect wildlife, we must first understand the microclimate patterns that characterize the seasons. As opposed to regional-scale weather, the microclimate is the suite of environmental conditions (temperature, moisture, etc.) experienced on a localized scale, such as a small patch of forest understory. To get this site-specific data, Phenology Project volunteers have deployed two new types of equipment: snow stakes and temperature sensors.

- Snow stakes: You may have already spotted these in some Snapshot photos. The 3-foot PVC pipes, marked every 2 inches, are held upright by a piece of rebar. Throughout the duration of the snow season (which is already going strong in Wisconsin!), we can use these stakes to measure the depth of snow at each site. Over 300 of these snow stakes have already been distributed, and we’re excited to see the snow depth data as we get photos back!

- Temperature sensors: Some sites have also received temperature loggers, which are small cylinders screwed directly into the side of a tree. Every 15 minutes, these loggers record air temperature, which will allow for detailed exploration of daily and seasonal temperature variation, as well as temperature extremes at each site. Winter temperatures are especially likely to impact the presence, behavior and abundance of our wildlife species, but we will also be interested in looking at temperatures across the full year.

Wildlife Soundscapes

While Snapshot cameras are excellent for seeing wildlife large enough to trigger a trail camera, there are many species that are too small to be detected regularly by cameras, such as songbirds, frogs and insects. Knowing where and when these species are present throughout the seasons can provide a more holistic picture of phenological change.

Over the next few months, we plan to distribute a small number of acoustic recorders to identify and monitor these species. These devices function much like a trail camera does, but they record audio instead of imagery. The units will record the soundscape throughout the entire annual cycle, which will provide valuable information on some of the species that would be missed by the trail cameras. Acoustic data could also help researchers improve monitoring of some vocalizing game species, such as wild turkeys. More generally, these recordings will shed light on the ways in which seasonal changes affect Wisconsin’s soundscapes.

Remote Sensing and Understory Vegetation

While many of us love Snapshot for its wildlife photos, the cameras are also capturing another important piece of the seasonal story: changes in vegetation.

Today, we have more tools than ever to observe vegetation phenology—not only through field observations, but also with satellites orbiting Earth. These satellites measure reflected light from vegetation, allowing researchers to detect when plants begin to turn green in spring, how green they become during the summer and when they start to shut down for the winter. This type of research, called remote sensing, consistently covers very large areas and provides an exceptional record of large-scale climate effects, forest health and long-term trends.

However, there is a catch: Satellite data mostly “sees” the top of the canopy—the overstory trees. As a result, changes occurring beneath the canopy, in shrubs or forest-floor vegetation, are often hidden from view.

Why does the understory matter? The understory includes wildflowers, shrubs and young trees, and supports a variety of ecological processes. Changes in this layer influence wildlife habitat, nutrient cycling and forest regeneration.

Because obtaining accurate observations of understory phenology from traditional remote sensing remains extremely challenging, time-lapse trail cameras are particularly valuable. These ground-based cameras see the forest floor directly and can capture a range of activity, including the emergence of spring wildflowers, grass and shrub growth, leaf-out below the canopy and snow cover.

Such information allows researchers to distinguish overstory phenology (the canopy) from understory phenology (the vegetation beneath it). Snapshot Wisconsin helps reveal changes occurring where satellites simply cannot see.

Summary

In the coming years, researchers at the DNR and UW-Madison will use these new sources of information to learn how Wisconsin's wildlife species are affected by seasonal changes, including how they use climatic cues to time important life-cycle events like reproduction, molting, migration and hibernation. Importantly, climate change is altering the timing of seasons in Wisconsin, and this research will help us better anticipate the species that are most phenologically sensitive and those that may be more resilient. We hope this new phase of research will generate insights into the science of phenology, help inform management and conservation of Wisconsin's wildlife species and add exciting new ways for volunteers to engage with Snapshot Wisconsin and their forest ecosystems! – Wyatt Cummings and Ting Zheng, University of Wisconsin-Madison research collaborators

The Snapshot Phenology Project Kickoff

The full Snapshot Phenology Project is now underway thanks to a collaborative effort between Snapshot volunteers, DNR staff, UW-Madison researchers and Wisconsin’s libraries and nature centers.

Last winter, 24 pilot volunteers put up snow stakes to do a trial run of the proposed setup for the Snapshot Phenology Project. Following input from these pilot volunteers and further testing from the Snapshot team, we launched the full project in the fall when 311 Snapshot Wisconsin volunteers were selected to install snow stakes at Snapshot camera sites throughout the state. Two hundred of these volunteers also received temperature sensors to install alongside the snow stakes.

To launch the full project, UW-Madison students and the Snapshot Wisconsin team worked together to make more than 300 snow stakes, package materials into individual Phenology Project kits and distribute them to Snapshot volunteers. However, unlike the compact trail cameras and batteries that the Snapshot team usually sends to volunteers, the roughly 3-foot-long PVC snow stake and 2-foot-long rebar that holds it in place proved challenging to send by mail.

To overcome this challenge and get the kits into the hands of participating Snapshot volunteers, we turned to partner organizations throughout Wisconsin—including county government offices, nature centers and libraries—to serve as distribution sites. From Ashland to Medford to Beloit, 35 partner sites stepped up to help deliver the kits to Snapshot volunteers.

The Nature Place (TNP) is one partner organization that helped to distribute equipment to volunteers in La Crosse County. “The Nature Place strives to be a place that connects community with nature, which is an obvious fit with Snapshot Wisconsin,” said Cindy Blobaum, TNP environmental education program manager.

“We loved meeting with the Snapshot volunteers. As a bonus, it was the first visit to TNP for many of them, so they are now aware of another compatible resource in their region,” Blobaum said. “It was amazing to hear the stories about the photos they captured on their cameras. One volunteer often sees bears, another can predict the weather by which animals are appearing and has a pretty good calendar of when to expect each one.”

Across the state in October and November, volunteers picked up the new equipment at local distribution sites and installed it as autumn leaves fell. For a few volunteers, installation occurred just in time for the season’s first big snowfall, around Thanksgiving.

Now, with snow stakes in the ground, temperature sensors deployed on the trees and Snapshot cameras recording the winter weather, Phenology Project volunteers are excited for what comes next. From educators to weather enthusiasts to those who just love the outdoors, a few Snapshot Phenology volunteers shared what they’re looking forward to:

“Data to be collected by the trail camera, as part of a volunteer citizen science project, will help our students to achieve a better understanding of animal behavior associated with varying climate conditions.”

– Russell Noland, director of the Merrill School Forest, Lincoln County

“When I heard about the Snapshot Phenology Project, I was immediately interested. I enjoy being a citizen scientist and have been involved in the Snapshot camera program for several years. I was excited when I was chosen to participate. Being interested in weather data, this program is a good fit for me.”

– Trace Frost, Phenology Project volunteer, Waushara County

“Just can't pass up an opportunity to help gather data that can be used to answer our questions about the natural world the plants and animals share with us.”

– Carol Eaton, Phenology Project volunteer, Oneida County

– Kyra Shaw, Ph.D.

How Do Animals Stay Warm?

Nothing beats coming home to your warm house on a cold winter day, putting on your coziest pajamas and curling up under a soft blanket with a cup of hot tea or cocoa. Humans have come up with all kinds of hacks to stay warm in colder climates: fires, shelters, furnaces, jackets, gloves, blankets, toe warmers and more. Have you ever wondered how wildlife endures the frigid temps all winter without these things? Similar to us, wild animals have developed hacks, or adaptations, to beat the cold and survive. These adaptations can be changes in physical form, behavior or both.

Our winter jackets work to keep us dry, block the chilling wind and trap our body heat. Many animals don winter jackets of their own! In the fall, white-tailed deer, foxes, coyotes and many other mammals grow thicker, longer and darker fur. This darker coat of fur helps them to blend into drab winter scenery and also absorb heat from the sun. It often consists of two layers, a woolly thick layer against the skin called an undercoat, which traps air and insulates the animal’s body heat, and an outer layer of long “guard hairs” to deflect wind and snow. Birds have a similar arrangement: an underlayer of soft, fluffy feathers, called down, to keep them warm and an outer layer of contour feathers to keep them dry. As an added warming effect, birds will puff up their feathers to trap additional air for insulation. Mammals similarly puff up their fur for warmth, an involuntary reaction called piloerection that’s triggered by the cold (think goosebumps!).

Animals have also developed a range of different internal adaptations to help fight the cold. Leading up to winter, many mammals will instinctually add on pounds of extra fat. This excess fat creates an additional layer of warmth under the skin and also acts as an energy reserve as food becomes scarce. Additionally, the circulatory systems of some animals, such as deer and rabbits, can adjust in colder temperatures to reduce heat loss. Blood vessels that run closer to the surface of the skin, like in extremities (e.g., limbs, ears, etc.), allow for heat dissipation. In winter, these animals reduce blood flow to their extremities in order to keep more warm blood in the core of the body to maintain vital organ functions.

What about behavioral adaptations to cold? Well, some animals just “pack their bags” to avoid winter altogether! This is called migration, and many species of birds in Wisconsin migrate to warmer areas through the winter months, such as sandhill cranes and hummingbirds. Other animals try to avoid harsh winter elements by denning down. Bears, badgers, chipmunks, skunks and other species will create burrows or dens underground for their winter refuge. While denning for winter, they experience decreased physiological activity, called torpor and hibernation. These animals will rely on excess body fat stores, food caches or both to survive this period.

The animals that haven’t migrated or denned down? They also show behavioral adaptations to help survive the cold! One study using Snapshot Wisconsin data analyzed the behavior of white-tailed deer through several winters. It found that deer adapted to conserve energy by restricting activity during the coldest portion of a 24-hour cycle. Deer, which are usually most active at twilight, became more active during the day in colder temperatures and deeper snow. Additionally, deer favored conifer-dominated landscapes on colder days, as these environments create warmer, more stable winter microclimates with less snow accumulation. These behavioral shifts in deer presumably reduce exposure to extremes and render more resilient species in increasingly variable winter climates. Visit our publications page for research on how wildlife survives winter and other studies on animal behavior using Snapshot Wisconsin data. – Liv Gripko

Snapshot Cameras Capture Wild Winter Scenes

Hey Snapshot Wisconsin volunteer camera hosts, we see you! And we’re especially thankful for your dedication during the cold and snowy months, when many of you lace up your boots, strap on snowshoes and head out into the chilly air to check on your trail camera. Thanks to you, we’re able to support scientific research projects, share Wisconsin wildlife with students statewide (and beyond!) and populate our robust Data Dashboard.

And, let’s face it, without you, we’d miss a lot of wonderful moments out in the wild. That includes this serene image of a deer in an Ashland County forest. The scene has an ethereal look thanks to a low sun and a likely touch of diamond dust, one of the nicknames for a meteorological phenomenon that can occur when conditions are just right. On a still, sunny day, when the air temperature is well below freezing, extra-tiny ice crystals may form. The cold air and low humidity prevent the crystals from growing larger or clumping together, resulting in a whisper-thin, ground-hugging cloud. This diamond dust, also called ice mist, sometimes looks like glitter suspended in the air, especially in full sun. In shaded forest landscapes, however, it can be more subtle, creating a dreamy soft focus.

Here are some of our other favorite winter captures that you made possible.

On the desert planet of Tatooine, old Ben Kenobi reminded a young Luke Skywalker that Sandpeople always rode their Banthas single file to hide their numbers. These Forest County fishers likely have something other than deception in mind, however. Fishers are solitary animals and generally only socialize during mating season, which happens to be late winter.

In taxonomy, the Sciuridae family includes squirrels of all sorts, from chipmunks and other ground squirrels to tree squirrels and flying squirrels (which glide rather than fly). Wisconsin is home to two species of flying squirrel, the larger northern flying squirrel and its smaller southern cousin. This determined Dunn County resident belongs to neither species: It’s a very common gray squirrel. Don’t mistake common for boring, however. Gray squirrels have a horizontal leap of around 10 feet and a vertical leap of about half that. According to a paper published in Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, researchers from the University of Louisville, Kentucky, found that gray squirrels can make split-second decisions about optimal trajectories when fleeing predators.

Meanwhile, over in Vilas County, this bobcat is on thin ice. Fortunately, these all-terrain animals have some adaptations that come in handy, or should we say paw-y, in snowy and icy conditions, including feet that are proportionally large for their body size. While the felines may seem elusive, bobcats are fairly common and widespread in our state. According to our Data Dashboard, they’ve been captured by Snapshot cameras like this one throughout western and northern Wisconsin.

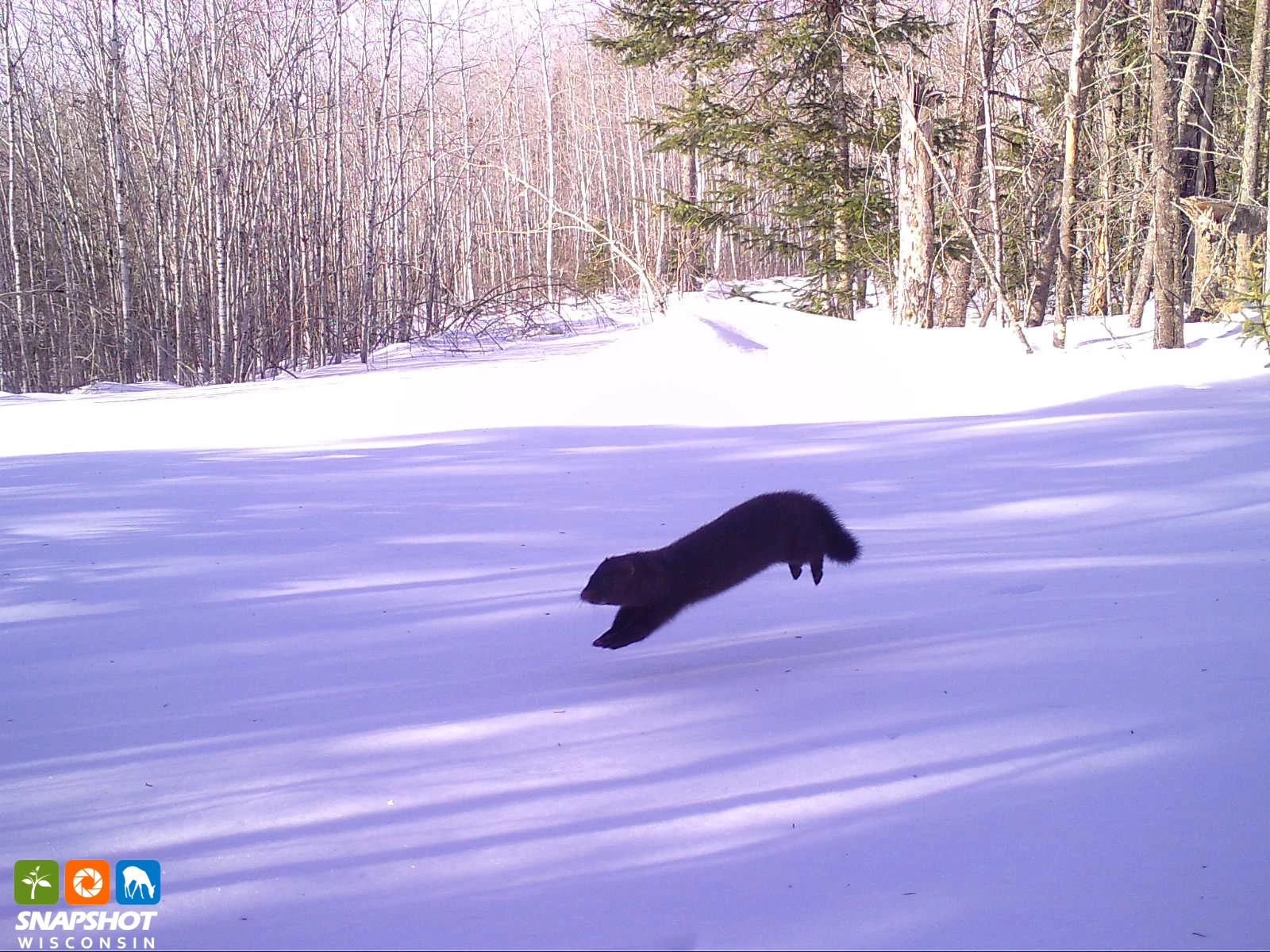

Minks are expert divers even, apparently, when the water they’re plunging into is snow. These semi-aquatic carnivores remain active all winter and have been documented hunting under both ice and snow. The opportunists will happily eat anything they can catch, from crustaceans and amphibians to small rodents. This mink, caught mid-pounce in Douglas County, may have picked up the sounds of a tasty vole beneath the snow thanks to its exceptional hearing.

This ruffed grouse is stepping out in Vilas County, putting its best foot forward for winter—literally. In autumn, the birds grow rows of modified scales called pectinations on their toes. These comb-like structures provide better traction for walking on snow and ice before being shed in spring. Ruffed grouse are a relatively well-studied species, but most of the research has focused on how best to manage habitat. Research scientists at the DNR’s Office of Applied Science, also home to Snapshot Wisconsin, are currently investigating how variable and changing winter conditions may affect the birds in our state now and in the future. – Gemma Tarlach

Hats Off To The Natural Resources Foundation Of Wisconsin

Snapshot Wisconsin wishes the Natural Resources Foundation of Wisconsin a very happy 40th anniversary. Founded in 1986, its mission is to protect Wisconsin’s lands, waters and wildlife by providing funding, leading partnerships and connecting all people with nature. The organization is a proud partner of Snapshot Wisconsin and supports the project by providing funding through donations and merchandise sales. To learn more, visit its webpage.