Field Notes Newsletter May 2021

The research team finished collaring animals and are analyzing the data they’ve collected. They have been organizing data, looking through the datasets and starting the first round of analyses. Soon, they will be ready to share what they are learning from their data.

In this edition of the newsletter, the research team shares a new timeline for when they expect to have results for each analysis in this study. This timeline is the clearest overview to date of all that is to come from the study, as well as when each piece of the puzzle is expected to be analyzed.

The timeline itself is broken into two halves. The first half covers how we will use our data to understand CWD's impact on Wisconsin's deer populations. Researchers are accomplishing this task by building a tool called an Integrated Population Model (IPM). The pieces of the IPM need to be built before the larger model can be assembled, and include analyses of CWD transmission rates, survival analyses and advancements in modeling process. The second half of the timeline is devoted towards other ways the same data can be used to further our understanding of deer, bobcats and coyotes. The secondary analyses don’t directly contribute to the IPM but are valuable in their own right.

The lead researcher of the study sat down to explain in more detail the timeline and what he expects to learn in the coming years.

PART I: PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER – THE INTEGRATED POPULATION MODEL

The Southwest Wisconsin CWD, Deer and Predator Study released a timeline covering the rest of the project. Part I highlights the main product of this study, the Integrated Population Model (IPM). The study’s lead scientist, Dan Storm, discusses how the research team will build the IPM.

PART II: THE REMAINING DEER AND PREDATOR ANALYSES

In Part II, Dan Storm, the lead scientist of the study, covers the other analyses that the research team plans to finish before the study concludes. These analyses don’t directly feed in to the IPM but will be informative for other aspects of deer, bobcat and coyote management.

A BUCK'S JOURNEY – STORIES FROM THE SW CWD STUDY

To show some of the interesting stories that can come from the study’s GPS collars, the research team looks at how one buck used the land around him from September to December 2019.,

PART I: PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER – THE INTEGRATED

POPULATION MODEL

The main goal of the SW CWD study has always been to determine the past, current and future impact of CWD on deer populations in Wisconsin, and the main way the team will determine that impact is by building an Integrated Population Model (IPM). “The IPM is the tool that will give us an answer to our main questions about CWD and deer populations,” said Dan Storm, Deer Research Scientist and lead researcher for the SW CWD study.

The IPM is a type of population model that can simultaneously analyze all available sources of data on a population, including survival from collared deer, harvest rates, disease rates and recruitment estimates. This IPM is unique because it incorporates disease surveillance data into the model to link changes in disease prevalence to possible changes in deer demographics. “Incorporating a disease component into the model is a major innovation to the field,” said Storm.

The IPM is expected to be completed by the end of 2022, and completing it requires the assembly and analysis of several components to the model. The main components falling under three categories of analyses: transmission rates, model advancements and survival analyses. Storm discussed each of these components in more detail.

CWD Transmission Rates 2002-2018

Understanding how past CWD patterns have changed is crucial to the IPM. “We need to create the statistical underpinning [or framework] for how disease data enters into the IPM. We talk about CWD spreading and growing, but what are the actual changes through time of CWD prevalence?” Storm asked.

Special care needs to go into analyzing the data so that we can answer important questions about CWD in the state. “Is prevalence increasing at a steady rate or an increasing rate? How has CWD prevalence changed since we discovered it in 2002? Those are important questions as we think about the future of CWD in Wisconsin,” said Storm.

This analysis is already underway and is expected to be among the first analyses completed by the research team still this year.

Model Advancements

The next pieces of the IPM are model advancements. The IPM needs to account for complicated ecological processes like deer survival and disease transmission. However, current survival models don’t account for changing disease status, such as deer that were CWD-negative at capture but later acquired the disease. Incorporating a disease component requires innovations on the statistical side, which take time for the statisticians to develop and test. “There isn’t a ready-made formula for us to use,” said Storm. “It’s not plug and chug.”

One way that disease complicates the model is through mortality from CWD. The models that estimate CWD infection don’t estimate mortality from CWD. If CWD increases the rate of death of certain age classes, then there will be some age classes where prevalence may decline faster than others. The IPM needs to account for potential disparities like this.

The researchers are trying to make the model fit what is actually happening, as best as possible, so they are investing time into building a model flexible enough to account for complications like changes in CWD status and disproportionate mortality. “We are creating a model that will give us the most robust answer that we can get right now," Storm said. "With other wildlife studies, there are ready-made formulas they can use. We have to build the formulas before we can use them.”

Both model advancement analyses are expected to finish later this year.

Survival - Fawn And Adult Deer

The last components of the IPM are the survival analyses. These analyses use collar data to determine survival rates of Wisconsin deer across a range of ages and sexes.

Take fawn survival, for example. The fawn survival analysis will tell us how many deer are born and survive long enough to be added to the population each year. “Are we adding lots of new deer each year, or are we adding only a few new deer? Recruitment matters because a higher recruitment means the population can handle a higher mortality before issues arise. Knowing fawn survival helps identify what is influencing recruitment so we can think about how to impact it from a management perspective,” said Storm.

The adult survival component tells us what percentage of our deer are surviving till the next year. The data from the collared (adult) deer will be used here to determine survival rates for different age and sex groups. Besides being important for the IPM, this estimate will be useful to managers and County Deer Advisory Councils (CDACs) across the state.

Both the fawn and adult survival analyses will also help researchers see how CWD impacts survival. Learning what rates CWD-negative and CWD-positive deer survive will be critical for the IPM. “Since CWD likely impacts survival in some way, we are relying on the IPM [and the survival analyses] to give us the clearest look at what has already happened, what is happening and what is going to happen to the deer population,” said Storm.

The fawn survival analysis is expected to be completed by late 2021, and the adult survival analysis is expected to be completed in early 2022.

Prioritizing The IPM

Building the IPM is the highest priority for the researchers, since it is the main product of the study and answers the most time-sensitive questions about CWD. “Those answers come first,” said Storm. The research team will share their results and what those results mean in future editions of this newsletter, so stay tuned so you don’t miss out.

However, there is more to the story. The IPM is only the first half of the timeline. Storm and his colleagues also plan to use the same data to learn other lessons about deer, predators and CWD. If you are interested in reading about the analyses in the second half of the timeline, keep reading.

PART II: THE REMAINING DEER AND PREDATOR ANALYSES

The second half of the project timeline covers analyses that are not pieces of the IPM (see previous article for more on the IPM) but extract additional value from the data we’ve collected. Many of these analyses use data from collars to learn how deer and predators use the landscape. The CWD data can also tell us more about how CWD changes the movement of deer and at what point their movements might change. Dan Storm, Deer Research Scientist and lead researcher of the study, shares his thoughts on these eight deer and predator analyses.

Predator Analyses

Over 110 predators were GPS-collared during this experiment, and their locations will improve our understanding of how they use different habitats and what their survival rates are. The predator side of the project will produce three main analyses.

An analysis of predator movement and habitat use is one of the first analyses the research team expects to finish. This analysis focuses on how these predators move about the landscape. The researchers hope to learn which areas are favored by bobcats and by coyotes, as well as which habitat types they avoid.

Knowing the preferences of predators can tell Storm which areas are especially risky for fawns and does, as well as help him see how predators fit into the bigger picture of deer survival. This analysis of predator movement and habitat use is expected to be completed later this year.

The other two analyses aim to determine the survival rates of bobcats and coyotes. Whenever a collared individual stops moving for a significant period of time, its GPS collar releases a mortality signal. Members of the research team drive out to the location of the signal and determine how the individual died. Understanding these causes of mortality and how often they occur will help inform management of these species, such as through setting bobcat harvest quotas.

Both of these survival analyses are expected to be completed later this year.

Additional Deer Studies

The last five analyses relate to various aspects of deer life. They will tell us how deer use the landscape at different times of the year (including during hunting and breeding seasons) and how that land use hinders/facilitates CWD transmission. These analyses all have immense scientific value.

The analysis of juvenile dispersal is the first of these analyses that Storm and the research team plan to complete. Juvenile dispersal is a trait found in multiple mammal species, where males leave their mother at a young age and go somewhere else. This behavior is an effective way of avoiding inbreeding, but it could also be a way of spreading CWD.

Storm hopes to learn how the landscape shapes dispersal. Big rivers, highways and other large obstacles could block juvenile dispersal in certain directions and indirectly shape CWD spread. “We’ve seen that CWD doesn’t spread uniformly across the landscape. I wonder if that is driven by uneven dispersal of juveniles,” said Storm. Storm wants to learn what the average dispersal distance is and how much certain obstacles block movement.

Two other analyses look at the seasonal movement of deer and when deer come into contact with each other. “CWD spreads by a deer contacting another deer or by a deer shedding prions that are picked up by a different deer, so transmission must involve the social behavior and habitat use of deer. We want to know if there are certain times or places that deer congregate and potentially spread CWD to others,” said Storm.

Between these three deer analyses, researchers aim to answer key questions about the connection between deer behavior and CWD transmission. The juvenile dispersal analysis is expected to be completed in late 2022, while the deer contacts and seasonal movement analyses are scheduled for 2024. Expect the team to share more information on those analyses as we move into 2022 and beyond.

Hunting, Breeding And CWD

The last two analyses may be of special interest to the public. One investigates the point at which CWD changes a deer’s movement. At the end-stages of CWD, deer are very sick. They lose weight and become less aware of their surroundings. Storm wants to know how soon before death their movements change.

“The distribution of prions on the landscape can change drastically depending on how CWD-positive deer move,” said Storm. “If deer hardly move once the disease reaches a certain point, for example, then the amount of the CWD prion deposited in that area will increase. We also want to learn if deer stay in certain habitats while sick.”

Finally, the last analysis deals with changes in the movement patterns of deer during the hunting and breeding seasons. Take bucks, for example. Bucks are more likely to be CWD-positive than females, and Storm suspects that buck behavior is likely the reason. “Somehow bucks are exposed more,” said Storm. “One likely way could be through breeding, but there are also other ways bucks change their behavior. During the rut, they increase their movement quite a bit. They chase around females and fight with other males. Knowing how much their movement increases, as well as knowing how that increase differs for different age groups, helps us understand how the rut changes their exposure to CWD.”

Storm also plans to look into what effect the firearm hunting season has on deer movement. “If the hunting pressure disrupts breeding movement, CWD transmission could also change as a result,” said Storm. “The intersection of the rut, hunting dates, deer movements and hunting pressure… They are all tied together, and we want to know how.”

Researchers expect to be done analyzing the impact of CWD on deer movement by early 2023 and the impact of breeding and hunting seasons on deer movement later that same year.

Tying Parts I And II Together

“What we will be able to say [by the end of this study] is what the relationship is between how prevalent CWD is in an area and the impact on the local deer population. We are going to have some concrete results to report even this year,” confirmed Storm. “I want to start getting answers and coming to conclusions. If all goes to plan, it will be a little over a year from now that things will really ramp up with the big results from the IPM.”

Storm is also excited to get to the additional deer and predator analyses, but he will have to wait for those. “If we were to try to rush and get answers now, it would effectively be throwing away money and effort. We just finished collaring animals in the winter of 2020. We need to give them enough time to live out their lives and transmit their locations before we can run some of these analyses. The data isn’t only what you record at capture. You have to monitor those animals afterwards,” explained Storm.

Storm continued, “Plus, we made a huge investment of money, time and personnel for this project, so naturally we want to get as much information out of these deer as possible while still balancing the need for speedy answers.” Prioritizing the IPM first is that balance.

Subscribing to this newsletter or staying subscribed are the easiest ways to keep up to date with what researchers are learning about Wisconsin’s deer, CWD and predators. Also, feel free to check out the expanded project website and project newsletter index to read more about the Southwest Wisconsin CWD, Deer and Predator Study.

A BUCK’S JOURNEY – STORIES FROM THE SW CWD STUDY

The research team released (in the previous article) the project timeline for when the various analyses and products of the SW CWD study are expected to be finished. These analyses will contribute to our understanding of deer and CWD in new ways, including how deer move around.

As an example of the lessons we can learn from this study’s data, the research team decided to share the story about how one buck moved around in late 2019. As we go through his location data and see this buck’s journey, remember that this buck is one of over 800 adult deer that were collared for this project, and this location data represents only a few months of this deer’s life. There is much more to learn than what is discussed here, especially once the data from the other 800+ deer are combined and analyzed.

Turning On The Collar

This buck was collared on March 7, 2019. He was 154 lbs and somewhat skinny but not abnormally so for that time of year. Despite his smaller size, the crew still considered him an adult buck and pulled a small incisor tooth for aging. From the tooth's age, researchers believe he likely was born in 2015.

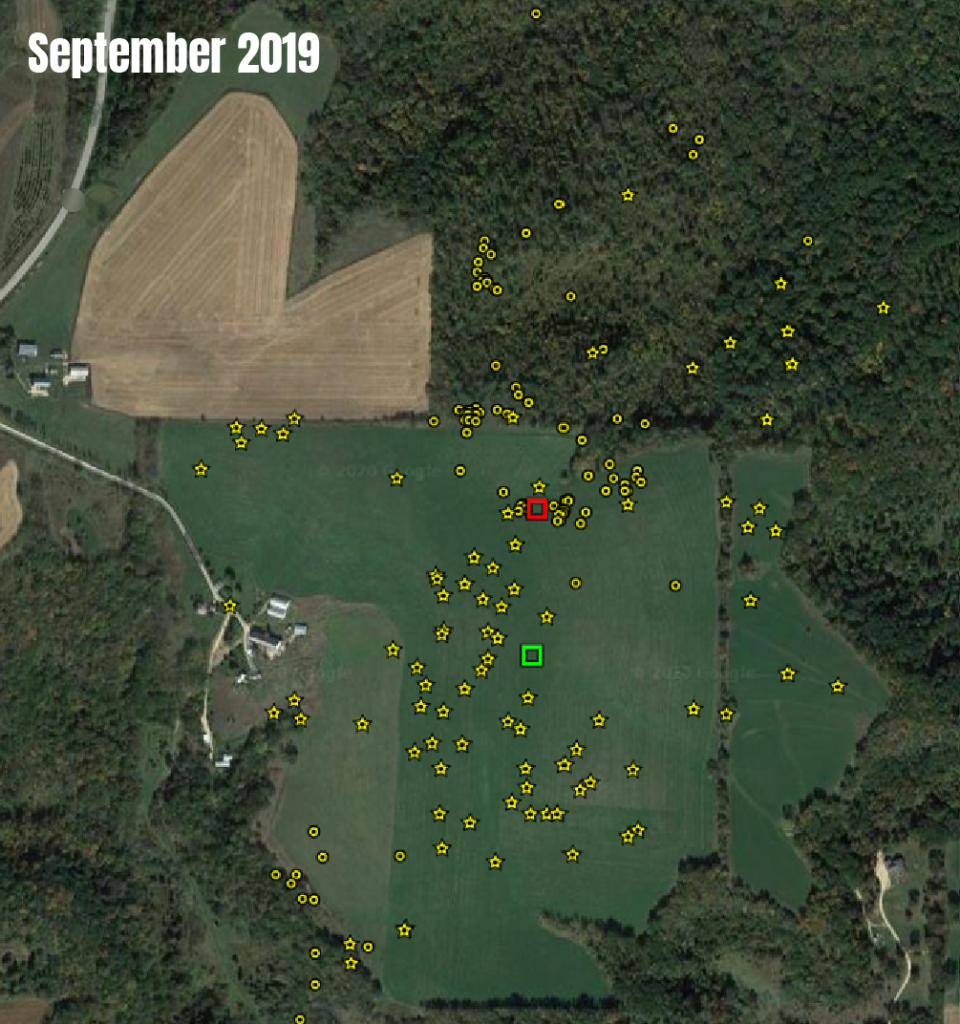

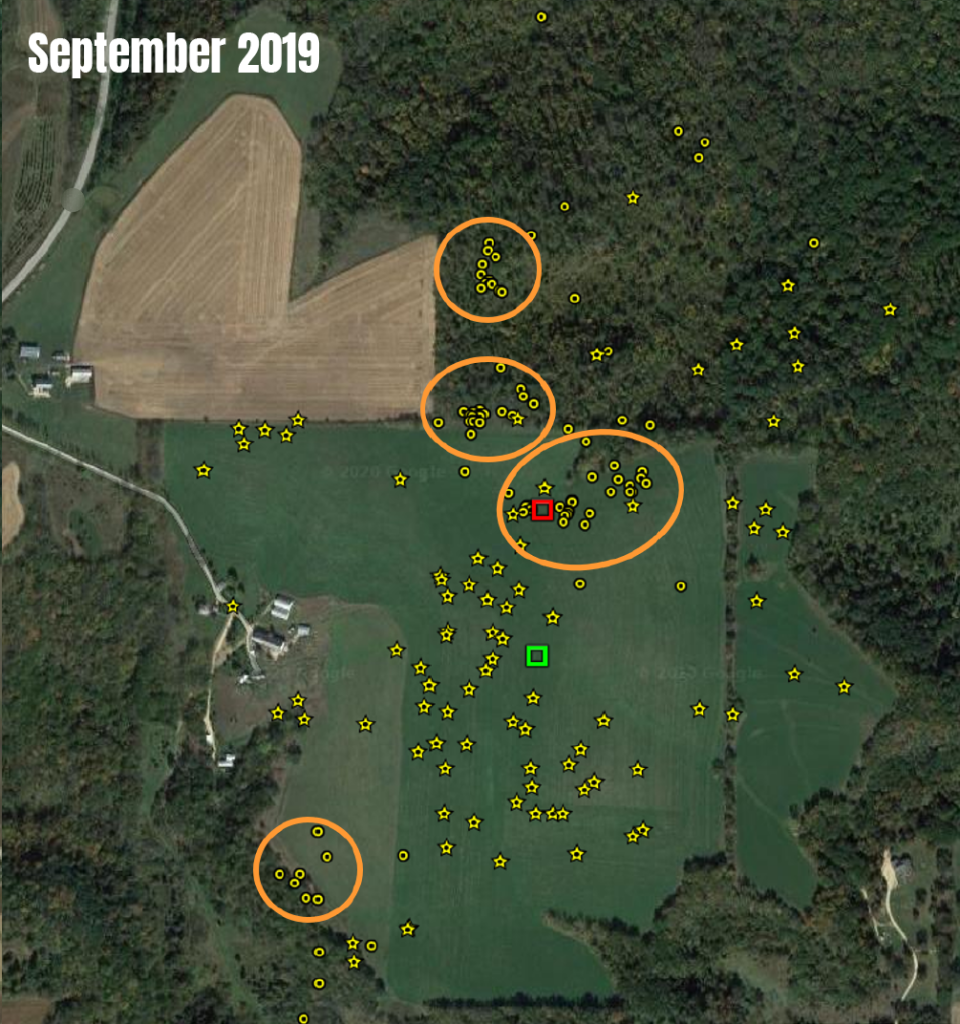

We’re going to look at his locations during the fall of 2019, when he was a 4-year-old. The first map shows the buck’s recorded locations throughout the month of September only. His location was taken every four hours with the circles representing day-time locations and stars representing nighttime locations. Locations are not displayed in any particular order. The red and green boxes are just the first and last locations of the month.

September 2019

First, let’s think about what is happening in September in the life of a buck. A lot of important changes happen in quick succession during the transition of seasons. The landscape is changing. Acorns drop, and the vegetation begins to die back. The velvet strips off bucks’ antlers, and bachelor groups break up. It also marks the start of the archery hunting season, so there is additional danger during this time.

From the location data, Storm noticed that the buck lived in a relatively small area, about 200 acres of land. Most of his locations were centered around a single field (in the center of the map). This field was a plain grass field at the time, neither grazed nor harvested for hay. The buck stayed in the woods or the edge of the field during the day and only ventured further out into the field during the night.

Storm also pointed out that the buck spent almost no time in agricultural fields. “Even in a highly agricultural landscape, deer can get the bulk of their food from the ‘natural’ landscape, at least for a time,” explained Storm.

In fact, the buck almost completely avoided the field on the northwestern corner of the map. Researchers aren’t sure why he avoided that field, but they are hoping that knowing the crop planted that year might give a clue. “When studying animal movements and habitat use, it is just as important to know which habitats animals are not using,” said Storm.

Another interesting observation Storm made was the clustering in the four circled regions shown above. Storm interpreted these areas to be the buck’s daytime bedding areas. Storm found it interesting that the buck bedded relatively close to the edge of the forest and grass fields, rather than deeper in the woods. “He seemed to bounce around from one bedding area to another, rather than use a single bedding area for multiple days in a row, observed Storm. “It will be interesting to see if we can learn why deer bed in certain areas on certain days. Is it based on wind direction or how hot/ cold it is at the time?” We don't currently know.

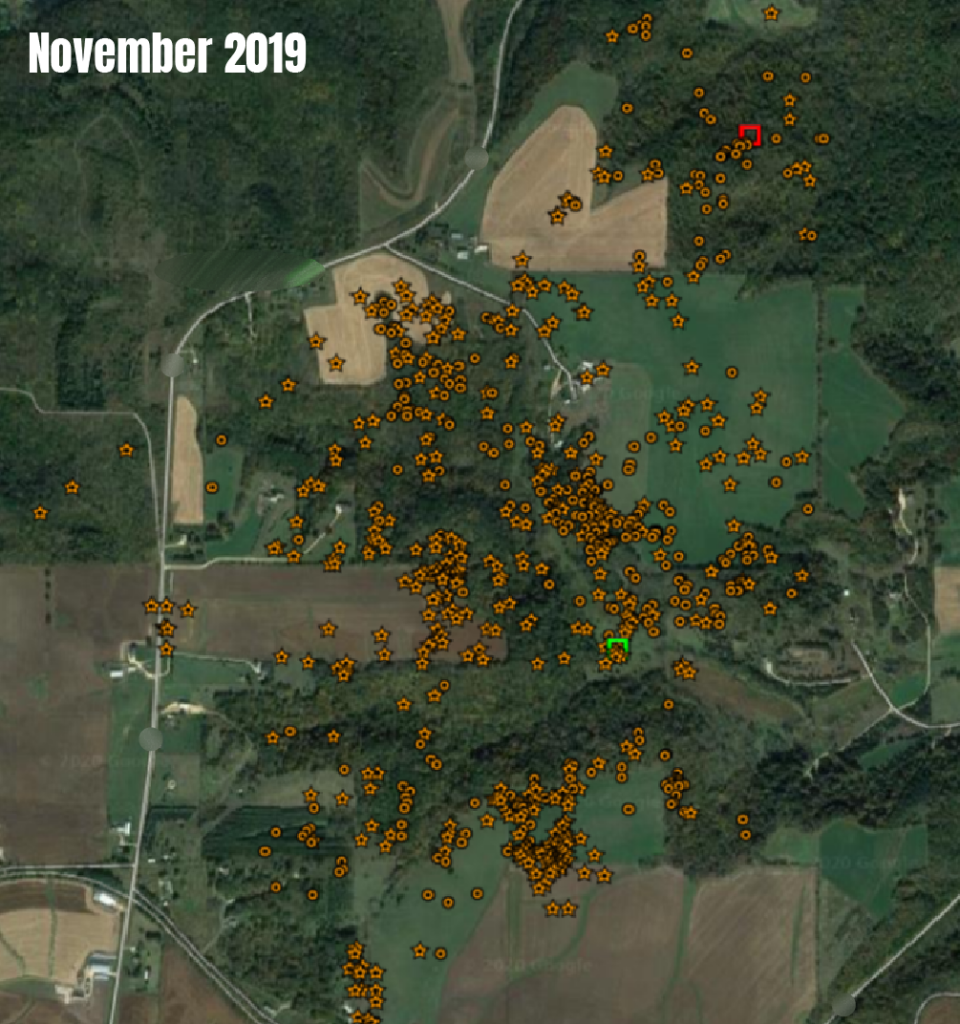

November 2019

Skipping ahead to November, we see the buck’s movements during the rut. Notice, there are a lot more points in November than there were in September; that’s because the researchers increased how often locations are recorded to better capture movements during the rut. The rate changed to once per hour, since the rut is when buck movement dramatically increases (as they search for mates) and the researchers are especially interested in learning about deer movements during this time.

The area that the buck used increased to around 600 acres, an area just under a square mile. His range expanded to nearly three times that of his September range.

Seeing an increase like this brings up important questions for Storm and the other researchers. Is the size of this expansion typical for a buck in November? How much do movement rates and home ranges change during the rut, and do they change as bucks age or become infected with CWD? All of these questions are important to understanding the link between deer behavior and CWD spread. “We’ll be able to answer these questions once we analyze all of our data,” confirmed Storm.

Another interesting change is that the buck’s range expanded in certain directions over others. Most of the expansion was to the west and south, not to the north or east. “It’s fun to speculate why that might be. Were there fewer does to the east? Or was there a bigger buck in those directions that he wanted to avoid?” It’s also interesting to look at the pockets that were avoided like the wooded ravine just south of the center of the map. Why didn’t he like it? Was it too steep? Again, these are questions that Storm and the researchers should be able to answer soon using the movement analyses.

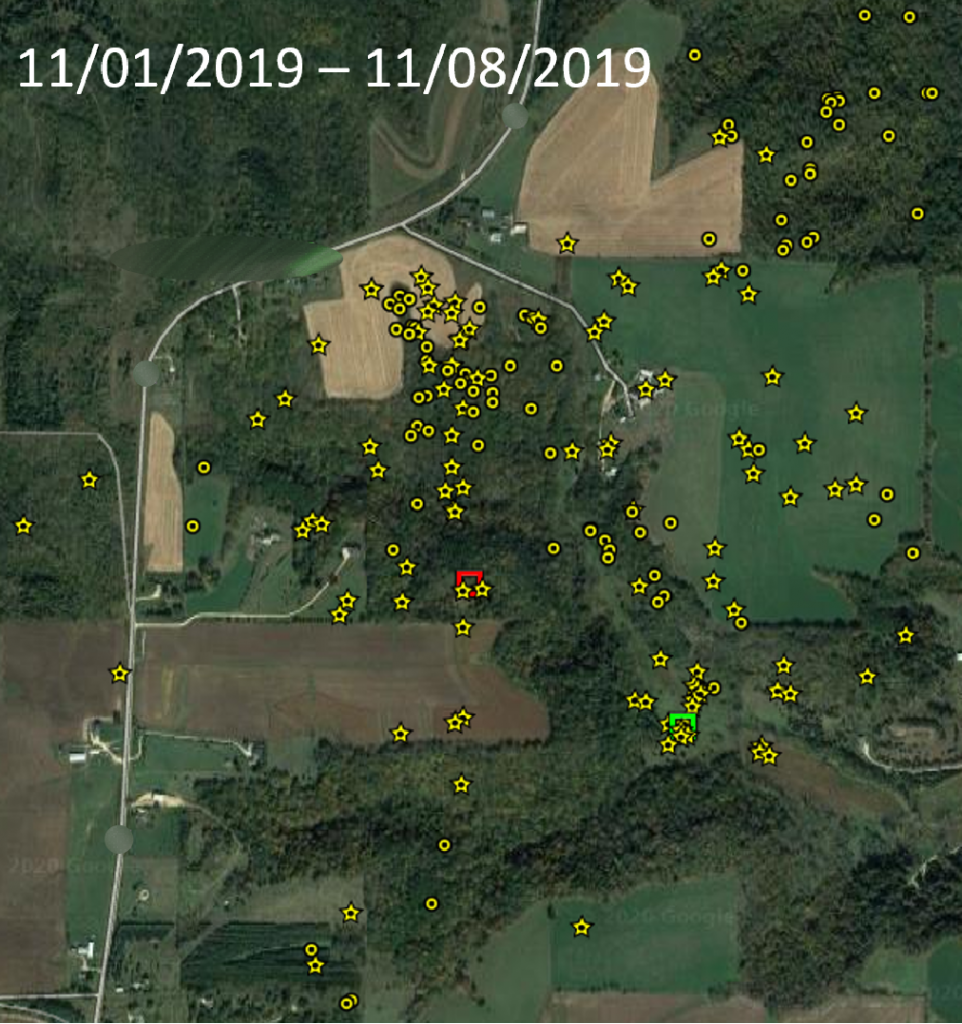

Let’s zoom in on November more, separating out the first two weeks of November and looking at them

individually.

Looking At The Rut More Closely

Comparing the first and second weeks of November, it becomes clear that the buck shifted his range to the south and west during this time. This shift documents a behavior that has frustrated many bow hunters.

Hunters could have seen a buck on their trail cameras or even from a tree-stand in the months leading up to bow hunting season. The hunter is all set to chase this buck, knowing that he frequents the northern area. But, to the hunters dismay, the buck doesn’t show when they are hunting. Sometimes that is how it is, especially during the rut.

Conversely, imagine a hunter in the south end of the map. They might have hunted hard throughout the first week of November and didn’t see a big buck. They get discouraged for a bit, but then a buck shows up suddenly and stays in the area.

Both situations happen each year, but the location data from this buck (and other bucks in the study) are helping tell us more about deer movement patterns and how quickly they change at key times of the year.

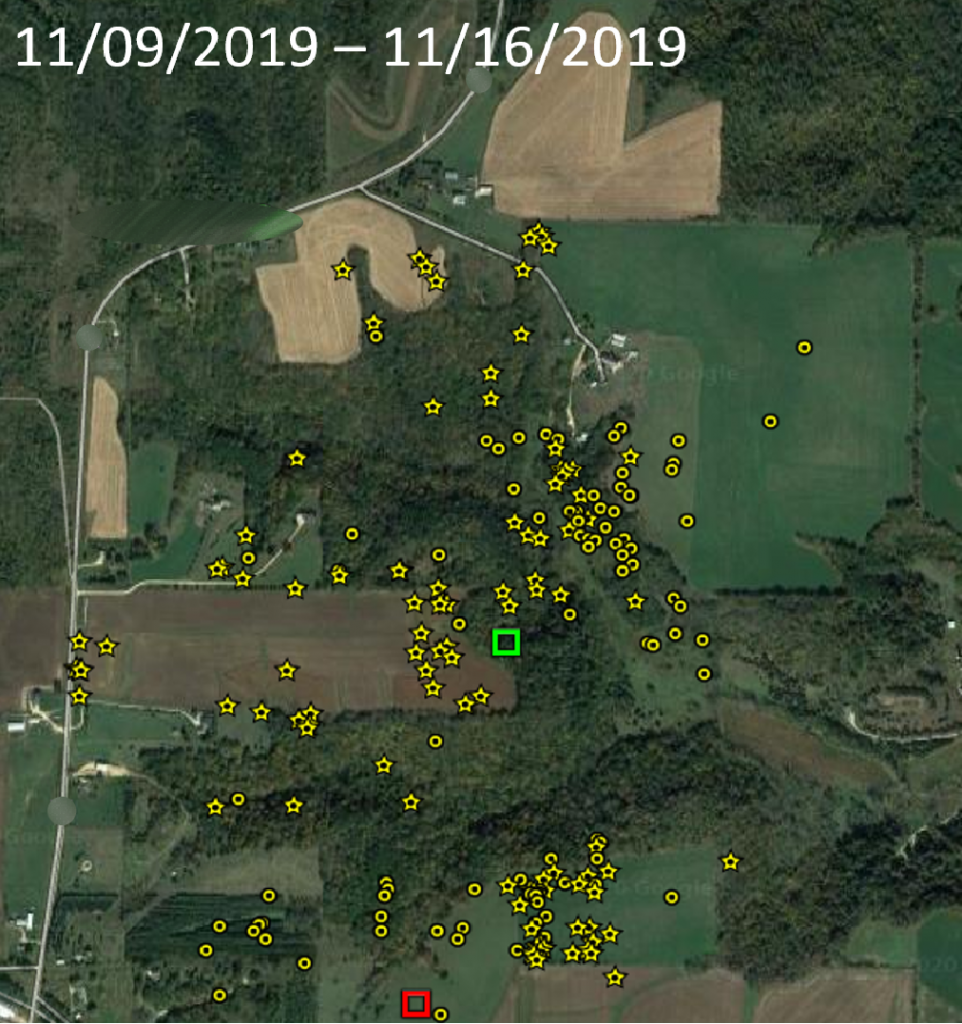

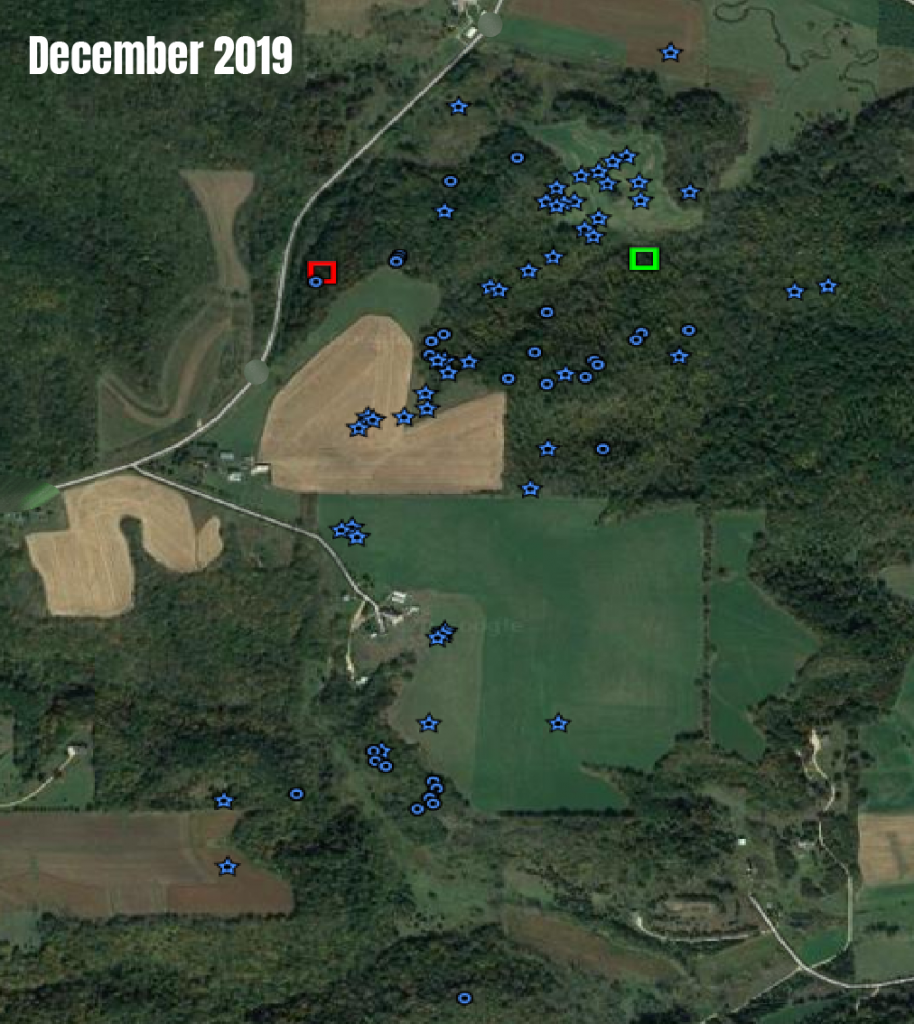

December 2019

It’s now December, and the buck survived the nine-day hunting season. He has reduced his home range to a core 100 acres, and there only minor movement outside that core range.

Storm noticed that the buck wasn’t using the grass field anymore, the one he relied so heavily on just a few months before. Is this shift due to the field being more exposed to the cold winter wind? Is it because he just wants to be closer to the food source he’s using? “These questions drive home the importance of factoring in variables related to the landscape and season into the team’s analyses. It also demonstrates that deer shift their habitat use around, finding different habitats more or less important as the seasons change,” explained Storm.

The Tip Of The Iceberg

The analyses being done by Storm and his fellow researchers will help us understand deer and CWD in new ways. “We’ve only scratched the surface on what we can learn from these locations. This example is just one deer out of over 800 in this study, and these locations are just a small fraction of his recorded locations,” said Storm. “It’s the tip of the iceberg. Imagine what we’ll learn from analyzing them all!”

The research team will continue to bring you stories like this one as they analyze the project’s data and learn more about deer behaviors. Check out the timeline for more information on when the various analyses are expected to be completed. Stay tuned for upcoming newsletters as well, where the team will share what they’ve learned.