Southwest Wisconsin CWD, Deer & Predator Study Newsletter

Issue 13: July, 2020

With the completion of the final capture seasons, the Southwest Wisconsin CWD, Deer and Predator study has reached an important milestone, Phase 2. This issue of Field Notes reflects on the study’s progress so far and details what the next phase of the project will look like.

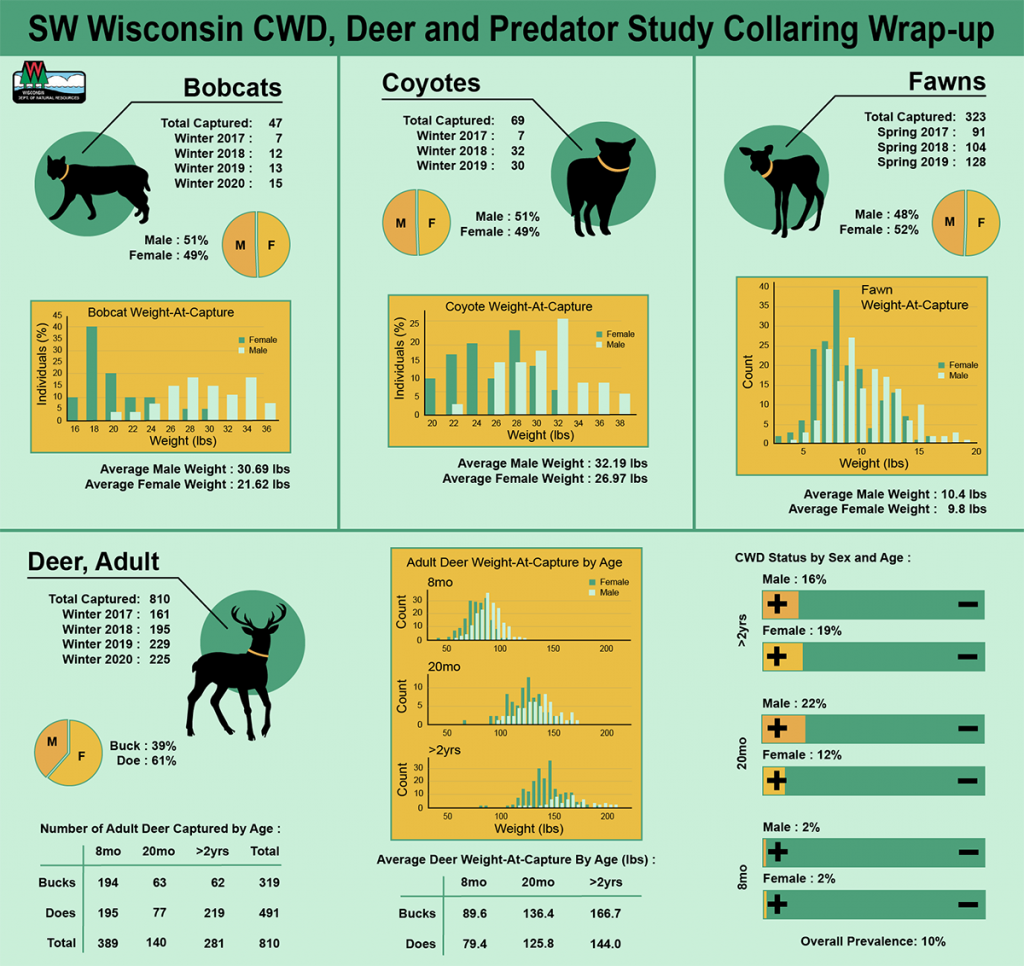

We also share summaries of the data collected during capture of the 1,249 animals that comprise the study’s large sample size. These data include graphs of weight-at-capture and sex distributions for all four animal groups, as well as the CWD test results for deer.

Lastly, we are asking for any of you who helped this study to share your favorite memories and pictures with us. Whether as a landowner, volunteer or whatever, we want to hear from you. Our next issue of this newsletter will focus entirely on the people who have helped us these last few capture seasons, so share with us your favorite moments, things you learned, and how being involved has impacted your life. You may get featured in the next issue!

Click the titles below to read this issue’s full articles and view our videos.

Turning Trials into Triumph The leaders of the field crew reflect on each of the capture seasons, sharing their thoughts about the challenges and obstacles they had to overcome to make the first phase of this study a success.

Infographic: Wrap-up of Final Capture Seasons

In this infographic, we break down some of the data we’ve collected so far from all 1,249 animals in this study. The breakdown is organized by animal group (Fawns, adult deer, bobcats, and coyotes) and includes summaries of the weights, sex distribution, and CWD status (for deer only) of each animal group.

Full Ahead: Modeling CWD in Wisconsin

With the infrastructure set up during the first phase of the study, we begin to move into the analysis phase, where the data is used to help deepen our understanding of the impact of CWD in Wisconsin. The project leads discuss how they are approaching modeling CWD in a such comprehensive way and why it was critical to capture and collar so many animals.

Submissions Wanted!

Share with us your favorite memories from the first few years of the project, and you might be featured in the next issue of Field Notes!

Turning Trials into Triumph

After four years and a couple thousand hours of labor, the Southwest Wisconsin CWD, Deer and Predator study is wrapping up its first phase. This first phase involved intensive field work, capturing and collaring over a thousand animals, and required a lot of work from staff and the public. However, the field crew has completed their final capture season, so the project’s focus is shifting to the next phase. Next, the team will be monitoring animals and analyzing the data from the collars.

At this transition point in the project, let’s look back at the field crew’s journey during Phase 1, starting all the way back to the first capture season.

Year 1

“Preparing for that first season was really difficult. We were rebuilding traps, picking up equipment from different parts of the state, contacting landowners, and trying to plan,” said Wes Ellarson, current Deer Project Coordinator and manager of the deer field crew for the study. “Most of the staff hadn’t done anything like it before, but we had help from a few people from the previous deer project.” The project coordinator at the time provided valuable training and advice to the new field crew.

But for some of the crew, the difficulty of the task in front of them hadn’t fully set in. “It’s hard to get someone to prepare for something they haven’t done before. It’s like telling them they are going to travel the world, but they have never been out of the state before. [The project coordinator at the time] was trying to explain to us how difficult it was going to be, and I don’t know that we really believed him. But he was right,” said Ellarson.

That first capture season was the hardest for the field crew due to more than their initial inexperience. Ellarson described the conditions they faced. “The weather was awful. It was a very muddy, warm winter. There was exposed ground almost all winter long.” For trapping deer, the best winter the crew could have is a very cold winter with lots of snow and ice, because it covers up all the natural food and forces deer to eat the corn used as bait in the traps. The weather also caused the woods to be muddy and torn up, which made it even tougher to set up and check traps. Despite the cruddy weather, the crew knew they had to max out their captures every season if they were to achieve the project’s ambitious capture goals. After all, who knew what the next year’s weather would bring?

Another big challenge that first year was testing for CWD. Testing for CWD requires surgically removing a very small square of skin from the deer’s rear end. This minor incision does not have any long-term effect on the deer and is similar to accidentally cutting their leg on a rock or branch. The difficulty comes from collecting and storing the tissue sample under harsh conditions in the field so that it remains viable until tested back in the lab. “[Initially] there was a lot of concern about how well it was going to work, how many viable samples we would get, but we’ve been really successful. Our percentage of viable samples was higher, I think, than most people expected,” said Ellarson.

Despite these initial challenges, the field crew was able to work through the kinks and had a moderately successful first capture season. A total of 266 animals were captured over the course of the first capture season, with 161 being adult deer.

Back at it again, Year 2

Year 2 started more solid, having some returning crew and a lot more experience across the board. The weather also was colder than the first, improving capture conditions for the crew. The better conditions helped the crew capture more animals the second year, bring the total animals captured that season to 343. Specifically, the number of adult deer captured that season rose to 195 (a 21% increase from the previous year).

Captures were a lot more successful for all species the second year, not just for deer. Predator numbers were fairly low the first year, so researchers adapted their tactics in year two. In addition to contracting with trappers to take over any trapped coyotes, the field crew upped their own trapping efforts to boost predator numbers. Thanks to a few tips from trappers, the crew dramatically improved their capture numbers for bobcats and coyotes, from 14 total predators to 44 predators.

Alex Hanrahan, the Predator Project Coordinator and manager of the predator field crew, explained why capturing predators was so hard. “With coyotes at least, because it is open season on them year-round, they are quite a bit more cautious. You have to be a bit subtler and sneakier when trying to catch them. With bobcats, it was more just trying to find them and where they liked to go. [Bobcat capture] also was about how to get their attention enough to draw them into the trap but not too interesting that it draws every racoon and opossum that goes by.”

Hanrahan said, “Our own capture efforts [seemed to] increase exponentially each year. With each additional year, we caught as many or more than the previous seasons.” Ellarson and Hanrahan accredited the field crew’s improved capture rate to getting more familiar with the study area and how predators used the area. The crew learned throughout the second season what types of habitat predators were hanging out in more frequently and adjusted the placement of their traps accordingly. Ellarson also mentioned an increase in their scouting efforts that helped improve the next few captures seasons.

“The hardest part was trying to decide which property to trap at and when to cut our losses,” said Hanrahan. “It was hard sometimes, because you may see a bobcat at a new property, when you haven’t seen one at the property you are currently trapping at for two weeks. It is tempting to move locations right away, and sometimes that is the correct move. But that may be the only time a bobcat goes through [that new property] for three months.”

The groundwork laid during the first, tough year also granted a social boon to the crew the second year. Thanks to the positive interactions and relationships built with landowners in the study area, more landowners were willing to join the study in year two. Dana Jarosinski, the Assistant Project Coordinator for the field crew, said, “Word travels. As we worked more and more with people, more landowners became aware of the project and allowed us to be on their property.” Since most of the study area is private land, cooperation with the landowners was critical to granting the team access to more land and capture locations.

All three coordinators mentioned how glad they were to work with so many landowners and volunteers. Ellarson, Hanrahan and Jarosinski have all tried to help the landowners get the most from their interaction, sharing information and letting them join in while the field crew was working on their property. The field crew even had landowners reach out to them and get involved, offering to bait and check traps for the team. “A lot of these people, I’ve become personal friends with,” said Ellarson. “I’ll stop to talk with them at the grocery store or wherever I run into them. We’ve done everything we could to build those personal relationships, and it really shows.”

Years 3 and 4, Best Yet!

The third and fourth winters had the best weather for captures. There was a lot of snowfall, and the snow stuck around for most of the season. Finding animal signs and dropping nets at night was easier, because the crew could see deer walking across the white snow better than exposed ground.

Ellarson said, “It seems like the weather has improved every year that we have done the project. But, we’ve also become more familiar with the study area, with the properties, with deer behavior, more people returning each year, and access to better properties. All those things have helped us get to our quota goals each year.”

Capture counts for seasons three and four were 400 and 240, respectively, although the fourth season had special circumstances. Enough coyotes were caught in the first three seasons that efforts were redirected towards capturing more bobcats that final season. Also, the last fawn capture season was cancelled (see the April issue for more information).

Between all four capture seasons, the total number of captured animals was 1,249. 810 adult deer were collared, exceeding our goal of 200 per capture season (800 in total). The researchers also collared 1,205 of the captured animals. The 44 animals that weren’t collared were either too small or enough of that species had already been collared by then.

“We are going to be left with our memories when this project is over. After capturing several hundred deer, the ones that stand out are the ones that were unusual or got the better of me. I’ll never forget [those],” said Ellarson.

One such animal that stood out to Hanrahan was a three-legged coyote. “We caught a three-legged coyote last year right before the polar vortex. I thought we would pick it up in a month, dead along the road. But somehow it is still alive in Illinois today.” The tenacity of that coyote is amazing.

Winding down Phase 1

With the first phase wrapping up, Ellarson took a few minutes to reflect on what this CWD study meant to him and to Wisconsin. Ellarson said, “Personally, being from Wisconsin, I would like to see good news regarding the future of our deer herd.” Ellarson grew up hunting deer with his father and still participates each year in Iowa County, where he currently lives. “One of the reasons I have been successful on this project is my connection to the area, the wildlife, and the people,” said Ellarson.

All three also hoped that their interactions with the public will help people see that they aren’t coming to a conclusion haphazardly. Jarosinski stated, “Data collection is huge to us. We are all very passionate about this project, and data collection is the most important piece. If you don’t have the data, then you can’t do the analysis.”

Ellarson added, “I think something that gets overlooked is how seriously this project is being taken. A lot of care went into collecting data. Everything has been double and triple checked, discussed with multiple people… and the volume of animals says a lot!”

Hanrahan explained, “A lot of the studies that have already been done don’t have the sample size we have. There is a lot of variation and things that you can’t control [in these studies], so having as much data as we have, under different types of weather, should provide a pretty robust sample size to help get a reliable understanding of the deer population in this area.”

Thanks to how well the field crew dealt with difficult conditions, they were able to match and exceed the project’s capture goals by the end of their last field season. A total of 1,249 animals were captured in the four years, and such a large sample size nicely sets up the next phase of the project for success as well.

For those interested in seeing some quick data from the capture seasons, check out the infographic following this article and keep reading to hear about what is in store next for the Southwest Wisconsin CWD, Deer and Predator study.

Infographic: Wrap-up of Final Capture Seasons

Full Ahead: Modeling CWD in Wisconsin

The Southwest Wisconsin CWD, Deer and Predator Study is entering its second phase. Most of the fieldwork is finished, so now researchers are diving into the analysis portion of the project as data keeps rolling in.

This CWD study is the largest, most comprehensive deer research project ever performed in Wisconsin, and it is also one of the biggest CWD studies in the world. Dan Storm, Deer Research Scientist at the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) and lead of the deer side of the project, said, “Its scale shows how seriously CWD is being taken.”

Storm continued, “CWD is here in a big way, and the problem is getting worse. Prevalence is increasing over time in the [counties] where it already exists and is spreading geographically. CWD is impacting a greater and greater portion of the deer population and portion of the people who interact with deer.”

Since its launch in 2016, the CWD Study has been focused on setting up the infrastructure needed for this project. The purpose of the capture component (Phase 1) of this project was to get the data generation machine flowing. GPS collars will continue to transmit their location until the animal dies or the collar’s battery runs out in 2-3 years, so the collaring phase was just the start of data generation, not the end. The animals need to keep living out their lives, and the GPS collars will continue to send us data about how they live and how they die.

Fortunately, the researchers have already received enough data from animals collared in past years to move into Phase 2 of the project. Phase 2 is where researchers begin to make sense of the stream of data they’ve been collecting. Storm said, “We’ve got a lot of good, quality data for this project. The more animals you catch, the more you can learn.” And if the 1,200+ animals that were captured and collared for this study are any indication, there is a lot researchers will learn about CWD in Phase 2.

What’s in store during Phase 2?

While data continues to flow in, Storm and his counterpart on the predator side of the study, Nathan Roberts, Furbearer Research Scientist at the WDNR, are ramping up the project’s data analysis phase. This phase aims to create a model for how CWD impacts our deer in Wisconsin. Roberts said, “We’ve realized that these [CWD] questions are really complicated. We can’t just look at a few variables at a time.”

Storm added, “These models are [therefore] very data hungry, because we have to account for so many different factors. Take survival, for instance. Right off the bat, you have differences in survival for each sex, age and CWD status. Just by having three different attributes to look at, you’ve already increased the sample size you need a bunch. Every little bit of complexity that’s added, increases the sample size needed.”

Roberts explained, “It is similar to how we think about human disease. You can look at the impacts of a disease on people, but that doesn’t tell you the whole story. To have a better understanding of what is going on, you need to look at some of the other factors like the impact of age or preexisting conditions. It’s the same with deer. You might think of predation even as a preexisting condition. We want to look at these important questions, not in isolation, but [together] with all these other factors that have the potential to impact the population.” Fortunately, Phase 1 was so successful at collaring a large sample size that the researchers will be able to look at CWD’s impact in a way that wouldn’t have been possible otherwise.

Why is modeling CWD so complicated?

CWD has the potential to change the likelihood that an infected deer dies from other causes, such as hunting, predation, and weather.

Let’s think of the deer population as a bag with ten marbles in it. Each year, three marbles are removed to represent annual deaths: one marble for hunting, one for predation and one for weather. At the same time, three marbles are added to represent that year’s new births, and the balance is maintained.

However, if CWD+ deer die more often during harsh winters, then two marbles need to be removed for weather (instead of one). Now, a total of four marbles are removed each year, yet only three are added. After a few years, there won’t be many marbles left in the bag.

Without incorporating these other variables and the potential of CWD to interact with them, researchers can’t fully understand the impact of CWD on deer.

Roberts said, “If we looked at these variables in isolation, it’s not very complicated. There [already] are models for individual factors like hunting or weather. What is unique here is that this study is comprehensive. We are integrating several sources of data into a single model.” With a large sample size and good analytical approach, such a comprehensive model is possible.

The researchers are currently at the beginning steps of building their model using the data that has already been collected, and more data will continue to flow in from the collars while the model is being built. Once the model is built and tested, the researchers will use the full dataset to analyze the effect CWD is having on the Wisconsin deer population.

David MacFarland, Wildlife Research Team Leader at the WDNR, said, “We are only at the halfway point. We still have a long road ahead of us.”

Upcoming Milestones in Phase 2

While we wait for the project to finish, we can look forward to a couple intermediate milestones. One upcoming milestone is the analysis of fawn survival. Since no new fawns are being collared, the monitoring period for these deer will finish soon, and the data can be analyzed.

Another milestone that our volunteers and nature lovers will enjoy is the analysis of juvenile dispersal. The year following their births, juveniles will begin dispersing around a larger area. In a few months, researchers will see the most recent batch of juveniles begin to disperse. Roberts said, “Each life stage presents different sets of challenges [for deer] and looking at each life stage gives us a fuller picture of the factors that influence deer populations throughout their lives.”

In addition to learning more about specific life stages of our deer, the researchers have also been expanding the team through collaborations. MacFarland mentioned bringing on research collaborators from the University of Wisconsin system and US Geological Survey during Phase 2. Two important collaborators, Alison Ketz, Assistant Scientist in the Department of Forestry and Wildlife Ecology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and Dan Walsh, Quantitative Ecologist at the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Wildlife Health Center, will play key roles in the model-building team.

Using our momentum

Phase 2 of the Southwest Wisconsin CWD, Deer and Predator Study is now underway and gaining initial momentum. The project’s success during Phase 1 set up the second phase to also be successful, and the researchers are confident that the project is in a great place. What we learn from this CWD study will better inform deer management decisions across the state, so stay tuned!

Roberts said, “In Wisconsin, wildlife are very important to our public. Wildlife and our communities are intertwined, so the public is very interested, not only in wildlife but having the information we need to make informed decisions regarding the management of wildlife.”

As a final thought, MacFarland said,

“If you care about deer, you should care about this project. CWD is a critical issue for deer management in the state. Like it or not, it is here and influencing our deer population.

If you are someone who values the ecosystems of the state, you should value this project. Deer are a primary influencer on our ecosystems. Not only on wildlife but on vegetation and other elements of the ecosystems. By understanding deer and their impacts, we learn about these critical ecosystems in the state.

If you care about conservation in Wisconsin, you should care about this project. The funding model we have for wildlife conservation across all of North America is based on funding through the sale of hunting licenses. Deer are the primary source of funding in Wisconsin. If there is something that is negatively impacting deer and therefore hurting deer hunting, then it’s negatively impacting the funding available for everything else we do in the state. The money that is generated not only funds deer management, but it funds prairie management, bird management, and the management of other important species.”

Stay tuned in this upcoming year for more from this study on the impact of CWD in Wisconsin.

What aspects of this project get the researchers excited?

MacFarland: “This project has been cool, because it is an example of what we can do as an agency and what we can do as a research group. The scale of this project is bordering on unprecedented, in terms of the number of animals collared and the scope of the project. This project is a testament to what is possible as an agency, especially when we have the cooperation of citizens.”

Storm: “For me, the biggest thing to learn [in Phase 2] is the main question: What really is the impact of CWD on the deer population? There are also so many other things [to learn] like how species interact with the landscape and how being infected influences how deer move across the landscape.”

Roberts: “I’m really excited to have a better understanding of the indirect impacts of carnivores on deer. We know that carnivores eat deer, nothing too surprising there. But with the work we are doing, we are able to look beyond that first level question of do they eat deer and ask what the potential indirect effects are. Does the type of habitat that they are using influence how deer move on the landscape? Being able to look at the indirect impacts of these species that all share the same landscape, that’s really fascinating, and I’m excited to see what we learn there.”

“That and… bobcats and coyotes are both secretive animals, because they are very cautious and elusive. They are common, but people don’t get to see them often. In this study, we have been able to look closely at those species in a way we haven’t been able to before. The number of animals and the technology we are using has really allowed us to look into the lives of these animals and the population as a whole. That’s been really fascinating to me.”

Submissions Wanted!

For the next issue of Field Notes, we want to hear from you! Our capture efforts have ended, and we want to look back and enjoy the good moments with our volunteers and staff.

We want you to share your stories and memories of volunteering for any capture effort (bobcat, deer, fawn, or coyote). You can share photos of yourself out volunteering, videos taken while searching, and stories of funny/cool moments you had while helping with these projects. If it was a memorable moment, we want to hear about it!

Our team will compile some of these memories and feature them in the next issue of Field Notes. If you want to participate, email your memories and stories to DNRDeerResearch@wisconsin.gov by July 31th to be considered for the next issue.