Field Notes October 2025

Reader survey results and more

Want to get notified when new newsletters come out? Sign up for the following topics on GovDelivery.

- Chronic Wasting Disease Updates - For emails about new project newsletters.

- Wisconsin Deer Research - For email updates on all deer projects being done by the Office of Applied Science.

For more Field Notes newsletters, please see the Field Notes Newsletter Index.

Welcome to a new edition of the Field Notes Newsletter, where we’ll discuss the results of a recent feedback survey sent to Field Notes subscribers and answer some frequently asked questions. We’ll also share details about upcoming changes to the newsletter moving forward. We’ll dive into a new publication from Dr. Marie Gilbertson that utilized data from the Southwest Wisconsin CWD, Deer and Predator Study to examine how white-tailed deer’s habitat use changes throughout the year, and what that might mean for CWD transmission. And finally, we'll share some big news about national recognition for our work.

Recapping Our Summer Survey

Early this summer we sent a feedback survey to subscribers of the Field Notes Newsletter. One of our main purposes in doing so was to gauge whether our audience would be interested in seeing Field Notes expand to cover deer research topics beyond that of the Southwest Study and its findings. If you were one of the over 1,500 people who responded to this survey, thank you! Here's what you shared with us.

Publication Sheds Light On Deer Habitat Seasonal Use

A new paper examines how the activity patterns of deer from the Southwest Study varied seasonally, including when, where and why deer might be most likely to encounter each other. Having this information allows researchers and managers to better understand when the likelihood of disease transmission, such as CWD, is highest, and to adjust management strategies accordingly.

National Accolades For Our Research

As the Southwest Wisconsin CWD, Deer and Predator Study wins the prestigious Wildlife Restoration Award, we pause to thank you for your interest in our work.

Recapping Our Summer Survey

Early this summer we sent a feedback survey to subscribers of the Field Notes Newsletter. One of our main purposes in doing so was to gauge whether our audience would be interested in seeing Field Notes expand to cover deer research topics beyond that of the Southwest Study and its findings. If you were one of the over 1,500 people who responded to this survey, thank you! Your feedback has been invaluable in helping us plan our future communications.

An overwhelming 91% of respondents let us know that they would be “likely” or “very likely” to continue reading Field Notes if our deer research topics were broadened. Moving forward, this means you can expect to see articles on updates and recent publications from a wider variety of WI DNR deer studies, deeper dives into the science behind deer behavior and biology, and features from even more WI DNR deer researchers and their collaborators. While the newsletter will still feature ongoing analysis and results from the data gathered during the Southwest Study, this expansion will give us room to share more deer science.

Additionally, our survey allowed space for subscribers to ask questions about deer or Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD), as well as an option to provide open-ended feedback on the newsletter. Due to the volume of responses, we won’t be able to provide a detailed answer for every question and comment in the newsletter. However, you can expect to see us address many of the more commonly asked questions in Field Notes editions to come.

To start, we were able to answer several frequently asked questions below:

- If CWD is not caused by a bacterium or virus, what causes it? Can it be killed?

- Where can I find a thorough fact sheet on CWD?

CWD is not caused by a living organism like a bacterium or virus; rather, it is a type of infectious protein called a prion. All mammals, including people, have proteins – long, precisely folded chains of amino acids – which carry out essential functions.

Prions, abnormally folded proteins such as those associated with CWD, can spread between organisms and even persist outside the body, including in soil. Once an individual is infected, the prions essentially co-opt healthy proteins, progressively increasing the number of misfolded proteins in the body. As prions accumulate in the individual, especially in the brain, the body becomes less able to perform essential functions.

CWD is a unique kind of prion which occurs in cervids (deer, moose, elk, reindeer, caribou). Although CWD has only affected cervids to date, it is part of a broader disease family known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies, which includes Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in humans.

While prions can be destroyed, they are extremely resistant to that destruction. Currently there is no cure or vaccine for CWD infection. You can learn more about CWD via the WI DNR’s CWD homepage or USGS’s National Wildlife Health Center.

- What’s happening with CWD, it seems to have gone away?

- Is CWD increasing?

- How can I learn the prevalence of CWD in a specific area? Can I request a map showing disease spread?

- Can we get data on the prevalence of CWD as it relates to deer age?

Unfortunately, CWD has not gone away and has continued to increase on the landscape both within Wisconsin and across North America.

To view the most up-to-date information on these metrics in Wisconsin you can check out the WI DNR’s Statewide Mapping App (adjustable by year) or CWD Prevalence in Wisconsin, a WI DNR webpage where you can view prevalence trends over time by infection area.

You can view CWD statistics for North America via the National Wildlife Health Center’s distribution map, which was most recently updated in July 2025, as well as their animation displaying the disease’s spread, 2000-2024.

- At what age do deer contract CWD?

- Can fawns get CWD?

Deer of any age can contract CWD. Older deer are more likely to be infected than younger deer because older deer have been exposed to the disease for longer.

- Do pregnant, CWD-infected does pass CWD to the fetus?

CWD prions have been found in the fetal tissue of infected does, suggesting that transmission can occur in utero. However, it appears that fawns do not always contract CWD from their infected mothers in utero.

- Have any elk been found to have CWD?

- Could elk get CWD from infected deer?

Elk can contract CWD, and have in states including Wyoming and Colorado. Although infection is always possible, no free-ranging elk in Wisconsin has yet tested positive for the disease.

- How can I tell whether a deer has CWD?

- How long before an infected deer shows signs of CWD?

- How long does it take a deer to die, from CWD infection to end stage?

The entire CWD infection period is believed to be 18-24 months. Infected deer will appear outwardly normal during most of this time, only showing symptoms during the final months or weeks prior to death from the disease.

After a deer is infected, it can take 18 months or longer before the animal shows visible symptoms of CWD. However, deer are infectious during much of this period.

While deer in the end stage of infection have some characteristic, visible symptoms, such as emaciation, drooling, stumbling or an appearance of general confusion, biologists rely on laboratory CWD tests to confirm infection.

- Why does the state allow high fenced game farms?

Wisconsin law, determined by the state legislature, allows for deer farms. Through its Farm-Raised Deer Program, the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection (DATCP) oversees the majority of rules related to these facilities.

- Can we return to “earn-a-buck policies’?

In 2011, a state law was passed prohibiting the DNR from implementing a requirement that hunters take an antlerless deer before taking their first antlered deer. A return to “earn-a-buck” policies would require action by state lawmakers.

- We also received a few non-CWD questions from folks regarding jobs at the WI DNR as well as asking for updates and information on other species.

To find current state job opportunities, anyone can visit wisc.jobs, select “Search by Agency” and select Department of Natural Resources.

For WI DNR updates on other topics and species, check out the agency’s email updates landing page. Here, you can sign up to receive email updates and information on many specific Wisconsin species, as well as the natural resources topics of your choosing. Subscriber preferences can be edited via the webpage at any time.

Many thanks again to those who took the time to participate in our survey. We look forward to answering more of your questions in future Field Notes editions!

Publication Sheds Light On Deer Habitat Seasonal Use

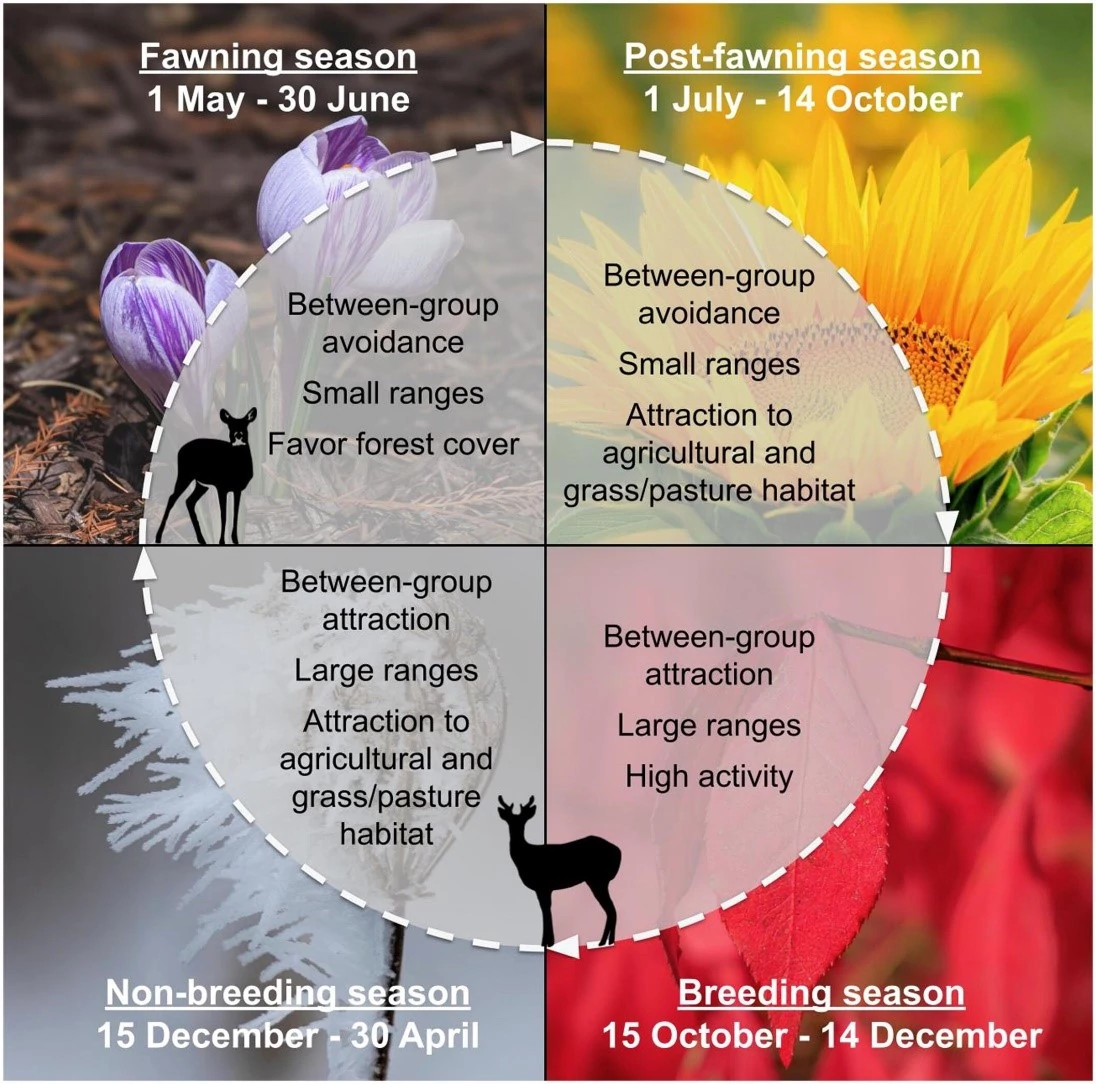

Earlier this year, Dr. Marie Gilbertson, a scientist specializing in wildlife disease ecology at UW-Madison, was lead author on a paper titled “White-tailed deer habitat use and implications for chronic wasting disease transmission.” The paper looked at movement data for 596 white-tailed deer that were GPS-collared between 2017 and 2020 for the WI DNR’s Southwest Wisconsin CWD, Deer and Predator Study. Primarily, Gilbertson was looking to see how the activity patterns of deer from the study varied seasonally, including when, where and why deer might be most likely to encounter each other. Having this information allows researchers and managers to better understand when the likelihood of disease transmission, such as CWD, is highest, and to adjust management strategies accordingly.

Before diving into results, it’s important to make a quick note about deer behavior. White-tailed deer are social animals and with a few exceptions, such as fawning and breeding season, tend to live and travel within their respective social groups. For does, these groups typically consist of related females and their young, whereas males can join up in “bachelor” groups during the winter and spring but typically prefer to fly solo during the ever-competitive breeding season. It is understood that CWD transmission is occurring within these groups through frequent, direct contact, such as when deer groom one another. However, the disease is also being transmitted between different deer groups that rarely if ever directly contact one another, and it’s important to understand how and when. Let’s take a look at Gilbertson’s key findings, season by season, starting with spring.

Spring

For this publication, spring refers to the general fawning season for white-tailed deer, May 1-June 30. In this spring season, does have the most noticeable behavior shift as they tend to isolate with their newly born fawns, favoring the protection of forest cover and reducing the size of their range. For this reason, direct transmission of CWD between deer groups is likely lower in spring than in other seasons.

However, one thing that Gilbertson found in her research is that does also tend to return to the same areas with their fawns year after year. Because of this, the continuous shedding of CWD prions (misfolded proteins which cause the disease) by infected does may create small but risky infectious pockets within the environment.

Summer

Summer here refers to deer behavior post-fawning, July 1-Oct. 14. In summer, does and their fawns will begin to venture further from forest cover and into spaces like crop fields and pastures in search of food. And while deer social groups still mostly avoid one other during this time, popular forage spaces may be shared by different groups. In this way, though direct contact between the groups is still relatively low, buildup of prions at food sources could provide a common transmission pathway. “One of the big questions here,” Gilbertson said, “is how important this kind of environmental transmission really is, relative to all the direct transmission we know is happening at other times of the year. We don’t know exactly how long CWD prions are infectious in the environment or how much we need to worry about this kind of transmission, so it’s a big focus of a lot of CWD research right now.”

Fall

Fall, defined here as Oct. 15-Dec. 14, encompasses the main breeding season for white-tailed deer and includes major changes to food availability as crops are harvested and green vegetation dies. During breeding season, dominant disease transmission pathways expand to include more between-group social interactions. As a result, direct transmission of CWD is likely highest during this time. These social interactions include transmission specifically through mating events but may also include indirect interactions through scrape sites.

In the fall, buck movement noticeably increases, and scrape sites serve as a kind of communication hub. To create a scape site, deer will paw at, rub or urinate on certain spots within their range. This territorial marking alerts does and other bucks within the area to their presence for mating purposes. Because multiple deer from different social groups might use and reuse the same scrape sites, they may become a hub for deer traffic as well as CWD transmission.

Winter

Winter refers to the non-breeding season, defined as Dec. 15-April 30 in the paper. During this time, deer tend to broaden their range as they search for more dependable food sources. Like the fall breeding season, this often leads to more interactions between groups as forage is relatively limited and deer will often congregate where it’s available. You may have even seen something like this for yourself, a large group of deer in a harvested corn or soybean field on a wintry day. Unfortunately, their sustained congregation at these feeding sites may mean disease transmission is happening both between the deer groups directly and through the environment itself.

In summary, these findings suggest that the main seasonal drivers of between-group disease transmission in white-tailed deer boil down to:

- Spring and summer: restricted ranges and relative isolation from other deer make direct CWD transmission less likely during this time. However, indirect transmission due to prions in the environment can still occur.

- Fall: primarily during breeding activity.

- Winter: primarily when deer congregate at limited forage sites.

Identifying these factors allows researchers and managers to better understand how disease transmission might be changing throughout the year and could have implications for future efforts to reduce CWD on the landscape.

National Accolades For Our Research

And finally, we’re happy to share that The Wildlife Society honored the Southwest Wisconsin CWD, Deer and Predator Study with its 2025 Wildlife Restoration Award in the Wildlife Research and Surveys category. The annual awards, announced in August, acknowledge outstanding projects supported by Wildlife Restoration funds (also known as Pittman-Robertson funds).

The Field Notes newsletter grew out of the study years ago as a way to share our research with you, and we deeply appreciate your continued interest in and enthusiasm for our work.