Snapshot Wisconsin May 2024

The snow has melted, April Showers have brought May flowers and Snapshot is ready for spring! In this newsletter, we cover one of our recent rare species sightings, why certain animals change colors across the seasons, which young animals you’re most likely to see during warmer Wisconsin weather, and how the newest class of newborns can contribute to science. Plus, tips for spring-time trail camera checks and the results of the latest global study, which includes data that Snapshot has contributed!

Rare Species Sighting: American marten in Bayfield County!

We talk about the recent sighting of Wisconsin's only state-endangered mammal.

Spring Through the Snapshot Lens

Find out which young animals are most frequently spotted in throughout the state.

How Young Contribute to Science

Learn about how DNR scientists utilize data surrounding newborn animals for ongoing research.

Considering Coloration Changes

We discuss why some animals change colors throughout their lives and what that can mean for trail camera detection.

Tips for Spring-Time Trail Camera Checks

Spring is here! Read on for some seasonal trail camera tips, from muddy trails to avoiding ticks.

We discuss a recent collaborative study published in the Nature Ecology and Evolution journal.

Rare Species Sighting: American marten in Bayfield County!

We are excited to share that an American marten has been spotted by a Snapshot Wisconsin trail camera in Bayfield County! This clear image of Wisconsin’s only state-endangered mammal is extra special for Snapshot Wisconsin, as they have been rarely spotted throughout the course of the project.

The American marten was reintroduced to Wisconsin after being extirpated in 1939 due to unregulated hunting and habitat loss. Today, this furbearer is mostly concentrated in the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest, although recently, a marten was detected on a trail camera for the Wild Madeline project on Lake Superior’s Madeline Island. This was the first detection on the island in a century, showing a promising future for marten and for trail cameras monitoring rare species!

Spring Through the Snapshot Lens

Spring means windows open to warmer weather, listening as bird songs once again become background noise, and watching the world grow around us. In the animal kingdom, spring marks the time when many young animals are just beginning to venture out into the freshly un-frozen world for the first time. If we’re lucky and highly observant, we might catch a glimpse of these newborns with our own eyes. Add a statewide network of trail camera photos to the mix however, and your odds are considerably higher.

So which young species might you see in the coming weeks? Some of the easiest to spot while outdoors in Wisconsin are deer, rabbits, squirrels, chipmunks, raccoons and birds. Trail cameras can help us see other species that are harder to find though, like black bears. Bear cubs, born in cozy dens during winter months, emerge in the springtime with their mothers as she seeks to regain calories lost during her winter slumber.

Trail cameras are an incredible resource that allows us to see young animals without disturbing them. However, if you happen upon baby wildlife, remember that a young wild animal’s best chance for survival is with its mother! Make sure to not disturb nests or denning sites, keep pets away and leave the site as soon as possible. If you think an animal is orphaned, see the DNR’s guidance on how to tell if you have found a truly orphaned animal.

How Young Contribute to Science

Young animals aren’t just fun to look at however, they can also be informative! Since 2017, DNR research scientists have been utilizing Snapshot Wisconsin photo data to help estimate fawn-to-doe ratios by county. “We use the classifications from volunteers of fawns versus antlerless deer from July and August,” said Jennifer Stenglein, Snapshot and DNR Quantitative Research Scientist, “That’s the time period where fawns should be easily identifiable by their spots.”

Trail camera hosts as well as volunteers on Zooniverse, a platform that helps facilitate classifications, aid this effort further by stating how many deer are present in the photo. “At the camera level, what we’re most interested in is, in any one trigger, what’s the maximum number of does and the maximum number of fawns. Those counts become really important.” Stenglein explained. Once researchers extract this data and craft county level estimates, the fawn-to-doe ratios are passed on to County Deer Advisory Councils (CDACS) for consideration when making future harvest quota recommendations.

Another project utilizing Snapshot’s young animal data seeks to study the movement and detectability of wild turkeys. Chris Pollentier, DNR Upland Gamebird Research Scientist, began trapping and tagging wild turkeys this past winter, attaching wing tags to all the trapped turkeys and transmitters to turkey hens. Now, he’s using these GPS transmitters and wing tags in conjunction with Snapshot trail camera images to monitor the movement of gobblers and hens and the reproductive success of their poults, or juvenile turkeys. “Hens should begin nesting in late-April to early-May and we hope to start seeing poults about a month later,” Pollentier said. “We’ll conduct brood counts periodically during the spring and summer as the poults grow and compare those counts to Snapshot Wisconsin trail camera photos.” The results of this project are still a few years out, but insights will help agencies better understand turkey behavior, habitat preference and recruitment metrics when making future management decisions.

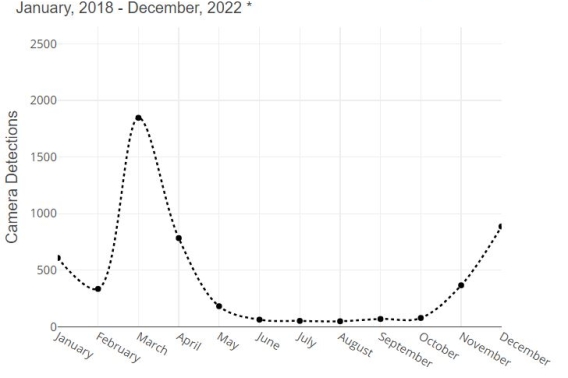

Anyone who’s interested in diving into some Snapshot data for themselves can check out the Data Dashboard. There, you can view species-specific data on either a statewide or county level and get a better understanding of how detections can vary among the seasons. As Snapshot Data Scientist Ryan Bemowski points out however, it’s important to remember that camera detections, and the data derived from them, still has nuance. “If you look at the Data Dashboard plots by season, a lot of the species, like fisher for example, drop really low in the summer. It’s not because they’re gone or migrating though, it’s just because they’re really hard to see.” So try the dashboard out for yourself, but if you see peaks and valleys in detections, think like a scientist and ask yourself ‘What else could be causing them?’

Considering Coloration Changes

As the seasons shift, one of the more notable changes for some species is their coloration. In Wisconsin, we commonly see this with white-tailed deer and snowshoe hares. In both cases the changes in color serve as a defense mechanism.

For example, when white-tailed fawns are born, they typically have lots of spots. “The first few weeks of a fawn’s life are critical,” says DNR Research Scientist Adam Mohr. “Their spotted coat acts as camouflage, mimicking the high contrast of dappled sunlight against a forest floor.” Mohr explains that the technical term for this specific type of camouflage is called “disruptive coloration”. In theory, the outlines of the spots serve as false edges, which make it even harder for would-be predators to detect the shape of the fawn itself. As fawns age and become inherently less vulnerable however, their spots begin to gradually fade. While this initial coloration change is tied more to age than season, mature deer will then proceed to seasonally alternate between a reddish coat in the summer months, and then a grayish tan in autumn and winter.

Like mature deer, snowshoe hares undergo a similar seasonal coloration change. When winter fades into summer, hares will shed their snowy white fur for a coat of woody brown, allowing them to conceal themselves more easily through the respective seasons. For this very reason, snowshoes tend to be more accurately classified in the winter months as it can be hard to distinguish them from brown cottontails in the summer. We can see evidence of this reflected in the Data Dashboard’s graph depicting hare detections by month. Just like with fisher, the dip in detections doesn’t mean the hares aren’t present, but rather that there is yet another factor to consider. In this case, color.

Tips for Spring-Time Trail Camera Checks

Using trail cameras can be a great resource for learning more about your local wildlife, catching great images of your favorite species, or just getting outside to enjoy some fresh air! Here are 5 tips to help you during your next trail camera check:

-

Watch for ticks: Use repellent on skin and clothing, wear the right outdoor clothing, and check for ticks after being outdoors.

-

Clear vegetation: Trim close or low-hanging vegetation in front of your trail camera to avoid false triggers.

-

Keep wildlife wild: Never feed or approach wildlife. It is important to observe wildlife from a respectful distance. Learn more on how you can keep wildlife wild and what to do if you identify a truly orphaned animal.

-

Avoid muddy trails: Using a muddy trail can be dangerous, damage the trail’s condition, and damage the ecosystem that surround the trail.

-

Leave it Alone: Try spreading out your camera checks to at least a month a part to avoid disturbing the area.

NEW PUBLICATION!

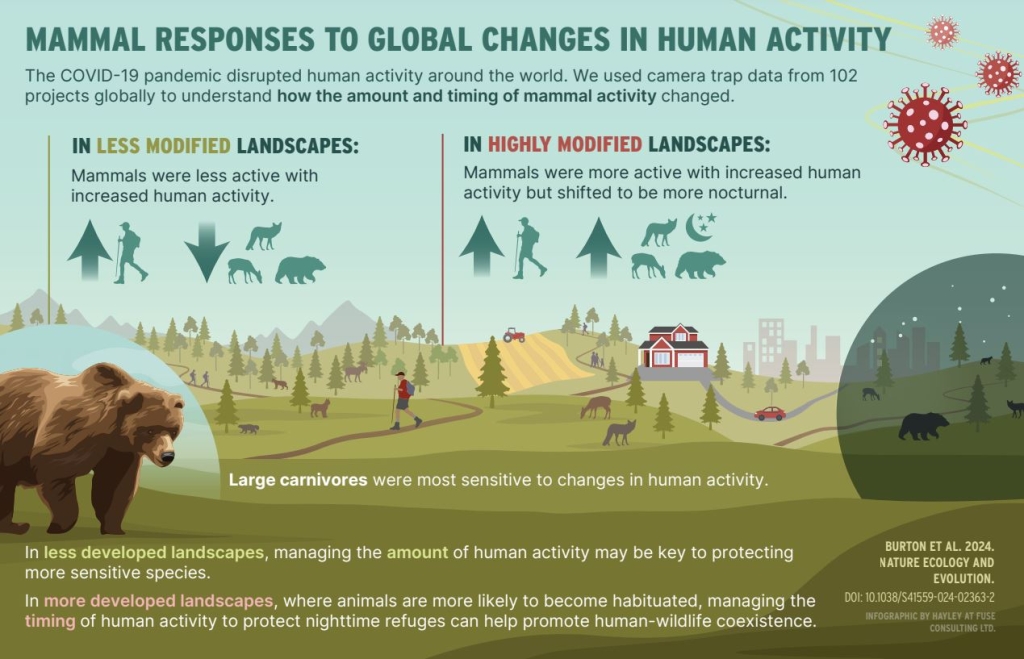

Snapshot Wisconsin data contributed to the publication of a recent worldwide study: Mammal responses to global changes in human activity vary by trophic group and landscape. The study compiled data from 102 different trail camera projects across the globe and analyzed the various ways animals responded to lessened human activity during the COVID-19 pandemic. The paper was published Nature Ecology & Evolution journal and has since been featured by several media outlets including the New York Times. Thank you to all our volunteers, without whom the data collection used in projects like this would not be possible!

Curious about other scientific publications that have been made possible by Snapshot? Visit the Snapshot Wisconsin publications homepage to learn more!